As discussed in Pattern Matching and Recursion, a well-known programming puzzle is to write a function that determines whether a string of parentheses is “balanced,” i.e. each opening parenthesis has a corresponding closing parenthesis, and the parentheses are properly nested.

For example:

| Input | Output | Comment |

|---|---|---|

'' |

true |

the empty string is balanced |

'()' |

true |

|

'(())' |

true |

parentheses can nest |

'()()' |

true |

multiple pairs are acceptable |

'(()()())()' |

true |

multiple pairs can nest |

'((()' |

false |

missing closing parentheses |

'()))' |

false |

missing opening parentheses |

')(' |

false |

close before open |

This problem is amenable to all sorts of solutions, from the pedestrian to the fanciful. But it is also an entry point to exploring some of fundamental questions around computability.

This problem is part of a class of problems that all have the same basic form:

- We have a language, by which we mean, we have a set of strings. Each string must be finite in length, although the set itself may have infinitely many members.

- We wish to construct a program that can “recognize” (sometimes called “accept”) strings that are members of the language, while rejecting strings that are not.

- The “recognizer” is constrained to consume the symbols of each string one at a time.

Computer scientists study this problem by asking themselves, “Given a particular language, what is the simplest possible machine that can recognize that language?” We’ll do the same thing.

Instead of asking ourselves, “What’s the wildest, weirdest program for recognizing balanced parentheses,” we’ll ask, “What’s the simplest possible computing machine that can recognize balanced parentheses?”

That will lead us on an exploration of formal languages, from regular languages, to deterministic context-free languages, and finally to context-free languages. And as we go, we’ll look at fundamental computing machines, from deterministic finite automata, to deterministic pushdown automata, and finally to pushdown automata.

prelude: why is this a “brutal” look?

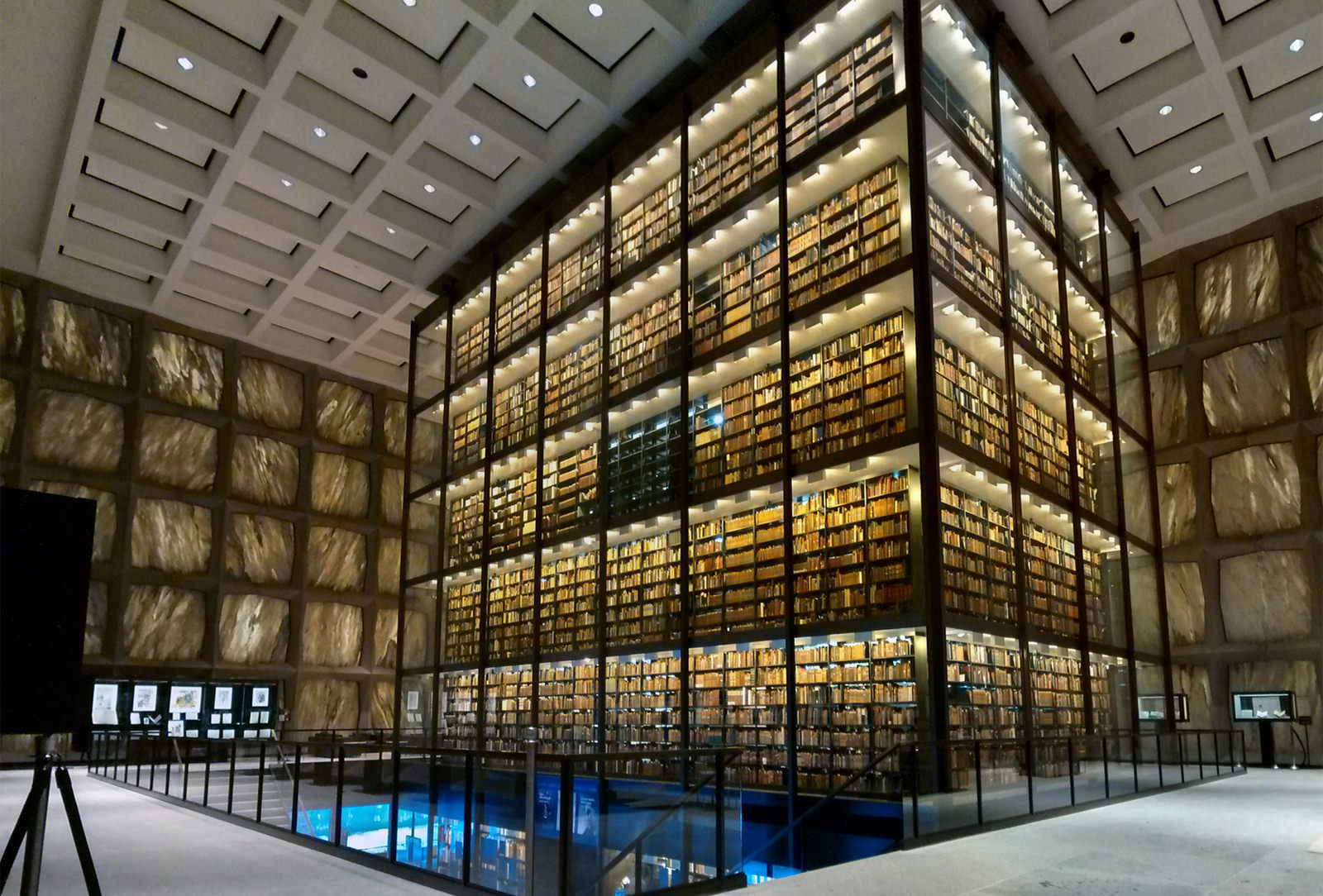

Brutalist architecture flourished from 1951 to 1975, having descended from the modernist architectural movement of the early 20th century. Considered both an ethic and aesthetic, utilitarian designs are dictated by function over form with raw construction materials and mundane functions left exposed. Reinforced concrete is the most commonly recognized building material of Brutalist architecture but other materials such as brick, glass, steel, and rough-hewn stone may also be used.

This essay focuses on the “raw” construction materials of formal languages and the idealized computing machines that recognize them. If JavaScript is ubiquitous aluminum siding, and if Elixir is gleaming steel and glass, pushdown automata are raw, exposed, and brutal concrete.

Let’s get started.

Table of Contents

Regular Languages and Deterministic Finite Automata:

- formal languages and recognizers

- implementing a deterministic finite automaton in javascript

- infinite regular languages

- nested parentheses

- balanced parentheses is not a regular language

Deterministic Context-free Languages and Deterministic Pushdown Automata:

- deterministic pushdown automata

- balanced parentheses is a deterministic context-free language

- recursive regular expressions

Context-Free Languages and Pushdown Automata:

- nested parentheses

- context-free languages

- why deterministic pushdown automata cannot recognize palindromes

- pushdown automata

- implementing pushdown automata

- deterministic context-free languages are context-free languages

Regular Languages and Deterministic Finite Automata

formal languages and recognizers

We’ll start by defining a few terms.

A “formal language” is a defined set of strings (or tokens in a really formal argument). For something to be a formal language, there must be an unambiguous way of determining whether a string is or is not a member of the language.

“Balanced parentheses” is a formal language, there is an unambiguous specification for determining whether a string is or is not a member of the language. In computer science, strings containing balanced parentheses are called “Dyck Words,” because they were first studied by Walther von Dyck.

We mentioned “unambiguously specifying whether a string belongs to a language.” A computer scientist’s favourite tool for unambiguously specifying anything is a computing device or machine. And indeed, for something to be a formal language, there must be a machine that acts as its specification.

As alluded to above, we call these machines recognizers. A recognizer takes as its input a series of tokens making up a string, and returns as its output whether it recognizes the string or not. If it does, that string is a member of the language. Computer scientists studying formal languages also study the recognizers for those languages.

There are infinitely many formal languages, but there is an important family of formal languages called regular languages.1

There are a couple of ways to define regular languages, but the one most pertinent to pattern matching is this: A regular language can be recognized by a Deterministic Finite Automaton, or “DFA.” Meaning, we can construct a simple “state machine” to recognize whether a string is valid in the language, and that state machine will have a finite number of states.

Consider the very simple language consisting of the strings Reg and Reggie. This language can be implemented with this deterministic finite automaton:

implementing a deterministic finite automaton in javascript

A Deterministic Finite Automaton is the simplest of all possible state machines: It can only store information in its explicit state, there are no other variables such as counters or stacks.2

Since a DFA can only encode state by being in one of a finite number of states, and since a DFA has a finite number of possible states, we know that a DFA can only encode a finite amount of state.

The only thing a DFA recognizer does is respond to tokens as it scans a string, and the only way to query it is to look at what state it is in, or detect whether it has halted.

Here’s a pattern for implementing the “name” recognizer DFA in JavaScript:

// infrastructure for writing deterministic finite automata

const END = Symbol('end');

class DeterministicFiniteAutomaton {

constructor(internal = 'start') {

this.internal = internal;

this.halted = false;

this.recognized = false;

}

transitionTo(internal) {

this.internal = internal;

return this;

}

recognize() {

this.recognized = true;

return this;

}

halt() {

this.halted = true;

return this;

}

consume(token) {

return this[this.internal](token);

}

static evaluate (string) {

let state = new this();

for (const token of string) {

const newState = state.consume(token);

if (newState === undefined || newState.halted) {

return false;

} else if (newState.recognized) {

return true;

} else {

state = newState;

}

}

const finalState = state.consume(END);

return !!(finalState && finalState.recognized);

}

}

function test (recognizer, examples) {

for (const example of examples) {

console.log(`'${example}' => ${recognizer.evaluate(example)}`);

}

}

// our recognizer

class Reginald extends DeterministicFiniteAutomaton {

start (token) {

if (token === 'R') {

return this.transitionTo('R');

}

}

R (token) {

if (token === 'e') {

return this.transitionTo('Re');

}

}

Re (token) {

if (token === 'g') {

return this.transitionTo('Reg');

}

}

Reg (token) {

if (token === 'g') {

return this.transitionTo('Regg');

}

if (token === END) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

Regg (token) {

if (token === 'i') {

return this.transitionTo('Reggi');

}

}

Reggi (token) {

if (token === 'e') {

return this.transitionTo('Reggie');

}

}

Reggie (token) {

if (token === END) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(Reginald, [

'', 'Scott', 'Reg', 'Reginald', 'Reggie'

]);

//=>

'' => false

'Scott' => false

'Reg' => true

'Reginald' => false

'Reggie' => true

This DFA has some constants for its own internal use, a state definition consisting of a function for each possible state the DFA can reach, and then a very simple “token scanning machine.” The recognizer function takes a string as an argument, and returns true if the machine reaches the RECOGNIZED state.

Each state function takes a token and returns a state to transition to. If it does not return another state, the DFA halts and the recognizer returns false.

If we can write a recognizer using this pattern for a language, we know it is a regular language. Our “name” language is thus a very small formal language, with just two recognized strings.

On to infinite regular languages!

infinite regular languages

If there are a finite number of finite strings in a language, there must be a DFA that recognizes that language.3

But what if there are an infinite number of finite strings in the language?

For some languages that have an infinite number of strings, we can still construct a deterministic finite automaton to recognize them. For example, here is a deterministic finite automaton that recognizes binary numbers:

And we can also write this DFA in JavaScript:

class Binary extends DeterministicFiniteAutomaton {

start (token) {

if (token === '0') {

return this.transitionTo('zero');

}

if (token === '1') {

return this.transitionTo('oneOrMore');

}

}

zero (token) {

if (token === END) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

oneOrMore (token) {

if (token === '0') {

return this.transitionTo('oneOrMore');

}

if (token === '1') {

return this.transitionTo('oneOrMore');

}

if (token === END) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(binary, [

'', '0', '1', '00', '01', '10', '11',

'000', '001', '010', '011', '100',

'101', '110', '111',

'10100011011000001010011100101110111'

]);

//=>

'' => false

'0' => true

'1' => true

'00' => false

'01' => false

'10' => true

'11' => true

'000' => false

'001' => false

'010' => false

'011' => false

'100' => true

'101' => true

'110' => true

'111' => true

'10100011011000001010011100101110111' => true

Our recognizer is finite, yet it recognizes an infinite number of finite strings, including those that are improbably long. And since the recognizer has a fixed and finite size, it follows that “binary numbers” is a regular language.

Now that we have some examples of regular languages. We see that they can be recognized with finite state automata, and we also see that it is possible for regular languages to have an infinite number of strings, some of which are arbitrarily long (but still finite). This does not, in principle, bar us from creating deterministic finite automatons to recognize them.

We can now think a little harder about the balanced parentheses problem. If “balanced parentheses” is a regular language, it must be possible to write a deterministic finite automaton to recognize a string with balanced parentheses.

But if it is not possible to write a deterministic finite automaton to recognize balanced parentheses, then balanced parentheses must be a kind of language that is more complex than a regular language, and must require a more powerful machine for recognizing its strings.

nested parentheses

Of all the strings that contain zero or more parentheses, there is a set that contains zero or more opening parentheses followed by zero or more closed parentheses, and where the number of opening parentheses exactly equals the number of closed parentheses.

The strings that happen to contain exactly the same number of opening parentheses as closed parentheses can just as easily be described as follows: A string belongs to the language if the string is (), or if the string is ( and ) wrapped around a string that belongs to the language.

We call these strings “nested parentheses,” and it is related to balanced parentheses: All nested parentheses strings are also balanced parentheses strings. Our approach to determining whether balanced parentheses is a regular language will use nested parentheses.

First, we will assume that there exists a deterministic finite automaton that can recognized balanced parentheses. Let’s call this machine B. Since nested parentheses are also balanced parentheses, B must recognize nested parentheses. Next, we will use nested parentheses strings to show that by presuming that B has a finite number of states, we create a logical contradiction.

This will establish that our assumption that there is a deterministic finite automaton—’B’—that recognizes balanced parentheses is faulty, which in turn establishes that balanced parentheses is not a regular language.4

Okay, we are ready to prove that a deterministic finite automaton cannot recognize nested parentheses, which in turn establishes that a deterministic finite automaton cannot recognize balanced parentheses.

balanced parentheses is not a regular language

Back to the assumption that there is a deterministic finite automaton that can recognize balanced parentheses, B. We don’t know how many states B has, it might be a very large number, but we know that there are a finite number of these states.

Now let’s consider the set of all strings that begin with one or more open parentheses: (, ((, (((, and so forth. Our DFA will always begin in the start state, and for each one of these strings, when B scans them, it will always end in some state.

There are an infinite number of such strings of open parentheses, but there are only a finite number of states in B, so it follows that there are at least two different strings of open parentheses that–when scanned–end up in the same state. Let’s call the shorter of those two strings p, and the longer of those two strings q.5

We can make a pretend function called state. state takes a DFA, a start state, and a string, and returns the state the machine is in after reading a string, or it returns halt if the machine halted at some point while reading the string.

We are saying that there is at least one pair of strings of open parentheses, p and q, such that p ≠ q, and state(B, start, p) = state(B, start, q). (Actually, there are an infinite number of such pairs, but we don’t need them all to prove a contradiction, a single pair will do.)

Now let us consider the string p’. p' consists of exactly as many closed parentheses as there are open parentheses in p. It follows that string pp' consists of p, followed by p'. pp' is a string in the balanced parentheses language, by definition.

String qp' consists of q, followed by p'. Since p has a different number of open parentheses than q, string qp' consists of a different number of open parentheses than closed parentheses, and thus qp' is not a string in the balanced parentheses language.

Now we run B on string pp', pausing after it has read the characters in p. At that point, it will be in state(B, start, p). It then reads the string p', placing it in state(B, state(B, start, p), p').

Since B recognizes strings in the balanced parentheses language, and pp' is a string in the balanced parentheses language, we know that state(B, start, pp') is recognized. And since state(B, start, pp') equals state(B, state(B, start, p), p'), we are also saying that state(B, state(B, start, p), p') is recognized.

What about running B on string qp'? Let’s pause after it reads the characters in q. At that point, it will be in state(B, start, q). It then reads the string p', placing it in state(B, state(B, start, q), p'). Since B recognizes strings in the balanced parentheses language, and qp' is not a string in the balanced parentheses language, we know that state(B, start, pq') must not equal recognized, and that state state(B, state(B, start, q), p') must not equal recognized.

But state(B, start, p) is the same state as state(B, start, q)! And by the rules of determinism, then state(B, state(B, start, p), p') must be the same as state(B, state(B, start, q), p'). But we have established that state(B, state(B, start, p), p') must be recognized and that state(B, state(B, start, p), p') must not be recognized.

Contradiction! Therefore, our original assumption—that B exists—is false. There is no deterministic finite automaton that recognizes balanced parentheses. And therefore, balanced parentheses is not a regular language.

Deterministic Context-free Languages and Deterministic Pushdown Automata

deterministic pushdown automata

We now know that “balanced parentheses” cannot be recognized with one of the simplest possible computing machines, a finite state automaton. This leads us to ask, “What is the simplest form of machine that can recognize balanced parentheses?” Computer scientists have studied this and related problems, and there are a few ideal machines that are more powerful than a DFA, but less powerful than a Turing Machine.

All of them have some mechanism for encoding an infinite number of states by adding some form of “external state” to the machine’s existing “internal state.”This is very much like a program in a von Neumann machine. Leaving out self-modifying code, the position of the program counter is a program’s internal state, while memory that it reads and writes is its external state.6

The simplest machine that adds external state, which we might think of as being one step more powerful than a DFA, is called a Deterministic Pushdown Automaton, or “DPA.” A DPA is very much like our Deterministic Finite Automaton, but it adds an expandable stack as its external state.

There are several classes of Pushdown Automata, depending upon what they are allowed to do with the stack. A Deterministic Pushdown Automaton has the simplest and least powerful capability:

- When a DPA matches the current token, the value of the top of the stack, or both.

- A DPA can halt or choose the next state, and it can also push a symbol onto the top of the stack, pop the current symbol off the top of the stack, or replace the top symbol on the stack.

If a deterministic pushdown automata can recognize a language, the language is known as a deterministic context-free language. Is “balanced parentheses” a deterministic context-free language?

Can we write a DPA to recognize balanced parentheses? DPAs have a finite number of internal states. Our proof that balanced parentheses was not a regular language rested on the fact that any DFA could not recognize balanced parentheses with a finite number of internal states.

Does that apply to DPAs too? No.

A DPA still has a finite number of internal states, but because of its external stack, it can encode an infinite number of possible states. With a DFA, we asserted that if it is in a particular internal state, and it reads a string of tokens, it will end up halting or reaching a state, and given that internal state and that series of tokens, the DFA will always end up halting or always end up reaching the same end state.

This is not true of a DPA. A DPA can push tokens onto the stack, pop tokens off the stack, and make decisions based on the top token on the stack. As a result, we cannot determine the destiny of a DPA based on its internal state and sequence of tokens alone, we have to include the state of the stack.

Therefore, our proof that a DFA with finite number of internal states cannot recognize balanced parentheses does not apply to DPAs. If we can write a DPA to recognize balanced parentheses, then “balanced parentheses” is a deterministic context-free language.

balanced parentheses is a deterministic context-free language

Let’s start with a recognizer that can implement DPAs. Now that we have to track both the current internal state and external state in the form of a stack.

const END = Symbol('end');

class DeterministicPushdownAutomaton {

constructor(internal = 'start', external = []) {

this.internal = internal;

this.external = external;

this.halted = false;

this.recognized = false;

}

push(token) {

this.external.push(token);

return this;

}

pop() {

this.external.pop();

return this;

}

replace(token) {

this.external[this.external.length - 1] = token;

return this;

}

top() {

return this.external[this.external.length - 1];

}

hasEmptyStack() {

return this.external.length === 0;

}

transitionTo(internal) {

this.internal = internal;

return this;

}

recognize() {

this.recognized = true;

return this;

}

halt() {

this.halted = true;

return this;

}

consume(token) {

return this[this.internal](token);

}

static evaluate (string) {

let state = new this();

for (const token of string) {

const newState = state.consume(token);

if (newState === undefined || newState.halted) {

return false;

} else if (newState.recognized) {

return true;

} else {

state = newState;

}

}

const finalState = state.consume(END);

return !!(finalState && finalState.recognized);

}

}

function test (recognizer, examples) {

for (const example of examples) {

console.log(`'${example}' => ${recognizer.evaluate(example)}`);

}

}

Now, a stack implemented in JavaScript cannot actually encode an infinite amount of information. The depth of the stack is limited to 2^32 -1, and there are a finite number of different values we can push onto the stack. And then there are limitations like the the memory in our machines, or the number of clock ticks our CPUs will execute before the heat-death of the universe.

But our implementation shows the basic principle, and it’s good enough for any of the test strings we’ll write by hand.

Now how about a recognizer for balanced parentheses? Here is the state diagram:

Note that we have added some decoration to the arcs between internal states: Instead of just recognizing a single token, it recognizes a tuple of a token and the top of the stack. [] means it matches when the stack is empty, [(] means match when the top of the stack contains a (, and _ is a wild-card that matches any non-empty token. We have also added two optional instructions for the stack: v to push, and ^ to pop.

And here’s the code for the same DPA:

class BalancedParentheses extends DeterministicPushdownAutomaton {

start(token) {

if (token === '(') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === ')' && this.top() === '(') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === END && this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(BalancedParentheses, [

'', '(', '()', '()()', '(())',

'([()()]())', '([()())())',

'())()', '((())(())'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'(' => false

'()' => true

'()()' => true

'(())' => true

'([()()]())' => false

'([()())())' => false

'())()' => false

'((())(())' => false

Aha! Balanced parentheses is a deterministic context-free language.

Our recognizer is so simple, we can give in to temptation and enhance it to recognize multiple types of parentheses (we won’t bother with the diagram):

class BalancedParentheses extends DeterministicPushdownAutomaton {

start(token) {

if (token === '(') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === '[') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === '{') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === ')' && this.top() === '(') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === ']' && this.top() === '[') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === '}' && this.top() === '{') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === END && this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(BalancedParentheses, [

'', '(', '()', '()()', '{()}',

'([()()]())', '([()())())',

'())()', '((())(())'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'(' => false

'()' => true

'()()' => true

'{()}' => true

'([()()]())' => true

'([()())())' => false

'())()' => false

'((())(())' => false

Balanced parentheses with a finite number of pairs of parentheses is also a deterministic context-free language. We’re going to come back to deterministic context-free languages in a moment, but let’s consider a slightly different way to recognize balanced parentheses first.

recursive regular expressions

We started this essay by mentioning regular expressions. We then showed that a formal regular expression cannot recognize balanced parentheses, in that formal regular expressions can only define regular languages.

Regular expressions as implemented in programming languages–abbreviated rexen (singular regex)–are a different beast. Various features have been added to make them non-deterministic, and on some platforms, even recursive.

JavaScripts regexen do not support recursion, but the Oniguruma regular expression engine used by Ruby (and PHP) does support recursion. Here’s an implementation of simple balanced parentheses, written in Ruby:

/^(?'balanced'(?:\(\g'balanced'\))*)$/x

It is written using the standard syntax. Standard syntax is compact, but on more complex patterns can make the pattern difficult to read. “Extended” syntax ignores whitespace, which is very useful when a regular expression is complex and needs to be visually structured.

Extended syntax also allows comments. Here’s a version that can handle three kinds of parentheses:

%r{ # Start of a Regular expression literal.

^ # Match the beginning of the input

(?'balanced' # Start a non-capturing group named 'balanced'

(?: # Start an anonymous non-capturing group

\(\g'balanced'\) # Match an open parenthesis, anything matching the 'balanced'

# group, and a closed parenthesis. ( and ) are escaped

# because they have special meanings in regular expressions.

| # ...or...

\[\g'balanced'\] # Match an open bracket, anything matching the 'balanced'

# group, and a closed bracket. [ and ] are escaped

# because they have special meanings in regular expressions.

| # ...or...

\{\g'balanced'\} # Match an open brace, anything matching the 'balanced'

# group, and a closed bracket. { and } are escaped

# because they have special meanings in regular expressions.

)* # End the anonymous non-capturing group, and modify

# it so that it matches zero or more times.

) # End the named, non-capturing group 'balanced'

$ # Match the end of the input

}x # End of the regular expression literal. x is a modifier

# indicating "extended" syntax, allowing comments and

# ignoring whitespace.

These recursive regular expressions specify a deterministic context-free language, and indeed we already have developed deterministic pushdown automata that perform the same recognizing.

We know that recognizing these languages requires some form of state that is equivalent to a stack with one level of depth for every unclosed parenthesis. That is handled for us by the engine, but we can be sure that somewhere behind the scenes, it is consuming the equivalent amount of memory.

So we know that recursive regular expressions appear to be at least as powerful as deterministic pushdown automata. But are they more powerful? Meaning, is there a language that a recursive regular expression can match, but a DPA cannot?

Context-Free Languages and Pushdown Automata

nested parentheses

To demonstrate that recursive regular expressions are more powerful than DPAs, let’s begin by simplifying our balanced parentheses language. Here’s a three-state DPA that recognizes nested parentheses only, not all balanced parentheses.

Here’s a simplified state diagram that just handles round parentheses:

And here’s the full code handling all three kinds of parentheses:

class NestedParentheses extends DeterministicPushdownAutomaton {

start(token) {

switch(token) {

case END:

return this.recognize();

case '(':

return this

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

case '[':

return this

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

case '{':

return this

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

}

}

opening(token) {

if (token === '(') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === '[') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === '{') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === ')' && this.top() === '(') {

return this

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

} else if (token === ']' && this.top() === '[') {

return this

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

} else if (token === '}' && this.top() === '{') {

return this

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

}

}

closing(token) {

if (token === ')' && this.top() === '(') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === ']' && this.top() === '[') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === '}' && this.top() === '{') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === END && this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(NestedParentheses, [

'', '(', '()', '()()', '{()}',

'([()])', '([))',

'(((((())))))'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'(' => false

'()' => true

'()()' => false

'{()}' => true

'([()])' => true

'([))' => false

'(((((())))))' => true

And here is the equivalent recursive regular expression:

nested = %r{

^

(?'nested'

(?:

\(\g'nested'\)

|

\[\g'nested'\]

|

\{\g'nested'\}

)?

)

$

}x

def test pattern, strings

strings.each do |string|

puts "'#{string}' => #{!(string =~ pattern).nil?}"

end

end

test nested, [

'', '(', '()', '()()', '{()}',

'([()])', '([))',

'(((((())))))'

]

#=>

'' => true

'(' => false

'()' => true

'()()' => false

'{()}' => true

'([()])' => true

'([))' => false

'(((((())))))' => true

So far, so good. Of course they both work, nested parentheses is a subset of balanced parentheses, so we know that it’s a deterministic context-free language.

But now let’s modify our program to help with documentation, rather than math. Let’s make it work with quotes.

context-free languages

Instead of matching open and closed parentheses, we’ll match quotes, both single quotes like ' and double quotes like "".7

Our first crack is to modify our existing DPA by replacing opening and closing parentheses with quotes. We’ll only need two cases, not three:

Here’s our DPA:

class NestedQuotes extends DeterministicPushdownAutomaton {

start(token) {

switch(token) {

case END:

return this.recognize();

case '\'':

return this

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

case '"':

return this

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

}

}

opening(token) {

if (token === '\'' && this.top() === '\'') {

return this

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

} else if (token === '"' && this.top() === '"') {

return this

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

} else if (token === '\'') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token === '"') {

return this.push(token);

}

}

closing(token) {

if (token === '\'' && this.top() === '\'') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === '"' && this.top() === '"') {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === END && this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.recognize();

}

}

}

test(NestedQuotes, [

``, `'`, `''`, `""`, `'""'`,

`"''"`, `'"'"`, `"''"""`,

`'"''''''''''''''''"'`

]);

//=>

'' => true

''' => false

'''' => false

'""' => false

''""'' => false

'"''"' => false

''"'"' => false

'"''"""' => false

''"''''''''''''''''"'' => false

NestedQuotes does not work. What if we modify our recursive regular expression to work with single and double quotes?

quotes = %r{

^

(?'balanced'

(?:

'\g'balanced''

|

"\g'balanced'"

)?

)

$

}x

test quotes, [

%q{}, %q{'}, %q{''}, %q{""}, %q{'""'},

%q{"''"}, %q{'"'"}, %q{"''"""},

%q{'"''''''''''''''''"'}

]

#=>

%q{} => true

%q{'} => false

%q{''} => true

%q{""} => true

%q{'""'} => true

%q{"''"} => true

%q{'"'"} => false

%q{"''"""} => false

%q{'"''''''''''''''''"'} => true

The recursive regular expression does work! Now, we may think that perhaps we went about writing our deterministic pushed automaton incorrectly, and there is a way to make it work, but no. It will never work on this particular problem.

This particular language–nested single and double quotes quotes–is a very simple example of the “palindrome” problem. We cannot use a deterministic pushdown automaton to write a recognizer for palindromes that have at least two different kinds of tokens.

And that tells us that there is a class of languages that are more complex than deterministic context-free languages. The are context-free languages, and they are a superset of deterministic context-free languages.

why deterministic pushdown automata cannot recognize palindromes

Why can’t a deterministic pushdown automaton recognize our nested symmetrical quotes language? For the same reason that deterministic pushdown automata cannot recognize arbitrarily long palindromes.

Let’s consider a simple palindrome language. In this language, there are only two tokens, 0, and 1. In our language, any even-length palindrome is valid, such as 00, 1001, and 000011110000. We aren’t going to do a formal proof here, but let’s imagine that there is a DPA that can recognize this language, we’ll call this DPA P.8

Let’s review for a moment how DPAs (like FSAs) work. There can only be a finite number of internal states. And there can only be a finite set of symbols that it manipulates (there might be more symbols than tokens in the language it recognizes, but still only a finite set.)

Now, depending upon how P is organized, it may push one symbol onto the stack for each token it reads, or it might push a token every so many tokens. For example, it could encode four bits of information about the tokens read as a single hexadecimal 0 through F. Or 256 bits as the hexadecimal pairs 00 through FF, and so on. or it might just store one bit of information per stack element, in which case it’s “words” would only have one bit each.

So the top-most element of the P’s external stack can contain an arbitrary, but finite amount of information. And P’s internal state can hold an arbitrary, but finite amount of information. There are fancy ways to get at elements below the topmost element, but to do so, we must either discard the top-most element’s information, or store it in P’s finite internal state temporarily, and then push it back.

That doesn’t actually give P any more recollection than storing state on the top of the stack and in its internal state. We can store more information than can be held in P’s internal state and on the top of P’s external stack, but to access more information, we must permanently discard information from the top of the stack.9

So let’s consider what happens when we feed P a long string of 0s and 1s that is “incompressible,” or random in an information-theoretic sense. Each token in our vocabulary of 1s and 0s represents an additional bit of information. We construct a string long enough that P must store some of the string’s information deep enough in the stack to be inaccessible without discarding information:

Now we begin to feed it the inverse of the string read so far. What does P do?

If P is to recognize a palindrome, it must eventually dig into the “inaccessible” information, which means discarding some information. So let’s feed it enough information such that it discards some information. Now we give it a token that is no longer part of the inverse of the original string. What does P do now? We haven’t encountered the END, so P cannot halt and declare that the string is not a palindrome. After all, this could be the beginning of an entirely new palindrome, we don’t know yet.

But since P has discarded some information in order to know whether to match an earlier possible palindrome, P does not now have enough information to match a larger palindrome. Ok, so maybe P shouldn’t have discarded information to match the shorter possible palindrome. If it did not do so, P would have the information required to match the longer possible palindrome.

But that breaks any time the shorter palindrome is the right thing to recognize.

Now matter how we organize P, we can always construct a string large enough that P must discard information to correctly recognize one possible string, but not discard information in order to correctly recognize another possible string.

Since P is deterministic, meaning it always does exactly one thing in response to any token given a particular state, P cannot both discard and simultaneously not discard information, therefore P cannot recognize languages composed of palindromes.

Therefore, no DPA can recognize languages composed of palindromes.

pushdown automata

We said that there is no deterministic pushdown automaton that can recognize a palindrome language like our symmetrical quotes language. And to reiterate, we said that this is the case because a deterministic pushdown automaton cannot simultaneously remove information from its external storage and add information to its external storage. If we wanted to make a pushdown automaton that could recognize palindromes, we could go about it in one of two ways:

- We could relax the restrictions on what an automaton can do with the stack in one step. e.g. access any element or store a stack in an element of the stack. Machine that can do more with the stack than a single

push,pop, orreplaceare called Stack Machines. - We could relax the restriction that a deterministic pushdown automata must do one thing, or another, but not both.

Let’s consider the latter option. Deterministic machines must do one and only one thing in response to a token and the top of the stack. That’s what makes them “deterministic.” In effect, their logic always looks like this:

start (token) {

if (token === this.top()) {

return this.pop();

} else if (token === '0' || token === '1') {

return this.push(token);

} else if (token == END and this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.recognize();

} else if (token == END and this.hasEmptyStack()) {

return this.halt();

}

}

Such logic pops, recognizes, halts, or pushes the current token, but it cannot do more than one of these things simultaneously. But what if the logic looked like this?

* start (token) {

if (token === this.top()) {

yield this.pop();

}

if (token === '0' || token === '1') {

yield this.push(token);

}

if (token == END and this.hasEmptyStack()) {

yield this.recognize();

}

if (token == END and this.hasEmptyStack()) {

yield this.halt();

}

}

This logic is formulated as a generator that yields one or more outcomes. It can do more than one thing at a time. It expressly can both pop and push the current token when it matches the top of the stack. How will this work?

implementing pushdown automata

We will now use this approach to write a recognizer for the “even-length binary palindrome” problem. We’ll use the same general idea as our NestedParentheses language, but we’ll make three changes:

- Our state methods will be generators;

- We evaluate all the possible actions and

yieldeach one’s result; - We add a call to

.fork()for each result, which as we’ll see below, means that we are cloning our state and making changes to the clone.

class BinaryPalindrome extends PushdownAutomaton {

* start (token) {

if (token === '0') {

yield this

.fork()

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

}

if (token === '1') {

yield this

.fork()

.push(token)

.transitionTo('opening');

}

if (token === END) {

yield this

.fork()

.recognize();

}

}

* opening (token) {

if (token === '0') {

yield this

.fork()

.push(token);

}

if (token === '1') {

yield this

.fork()

.push(token);

}

if (token === '0' && this.top() === '0') {

yield this

.fork()

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

}

if (token === '1' && this.top() === '1') {

yield this

.fork()

.pop()

.transitionTo('closing');

}

}

* closing (token) {

if (token === '0' && this.top() === '0') {

yield this

.fork()

.pop();

}

if (token === '1' && this.top() === '1') {

yield this

.fork()

.pop();

}

if (token === END && this.hasEmptyStack()) {

yield this

.fork()

.recognize();

}

}

}

Now let’s modify DeterministicPushdownAutomaton to create PushdownAutomaton. We’ll literally copy the code from class DeterministicPushdownAutomaton { ... } and make the following changes:10

class PushdownAutomaton {

// ... copy-pasta from class DeterministicPushdownAutomaton

consume(token) {

return [...this[this.internal](token)];

}

fork() {

return new this.constructor(this.internal, this.external.slice(0));

}

static evaluate (string) {

let states = [new this()];

for (const token of string) {

const newStates = states

.flatMap(state => state.consume(token))

.filter(state => state && !state.halted);

if (newStates.length === 0) {

return false;

} else if (newStates.some(state => state.recognized)) {

return true;

} else {

states = newStates;

}

}

return states

.flatMap(state => state.consume(END))

.some(state => state && state.recognized);

}

}

The new consume method calls the internal state method as before, but then uses the array spread syntax to turn the elements it yields into an array. The fork method makes a deep copy of a state object.11

The biggest change is to the evaluate static method. we now start with an array of one state. As we loop over the tokens in the string, we take the set of all states and flatMap them to the states they return, then filter out any states that halt.

If we end up with no states that haven’t halted, the machine fails to recognize the string. Whereas, if any of the states lead to recognizing the string, the machine recognizes the string. If not, we move to the next token. When we finally pass in the END token, if any of the states returned recognize the string, then we recognize the string.

So does it work?

test(BinaryPalindrome, [

'', '0', '00', '11', '0110',

'1001', '0101', '100111',

'01000000000000000010'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'0' => false

'00' => true

'11' => true

'0110' => true

'1001' => true

'0101' => false

'100111' => false

'01000000000000000010' => true

Indeed it does, and we leave as “exercises for the reader” to perform either of these two modifications:

- Modify

Binary Palindrometo recognize both odd- and even-length palindromes, or; - Modify

Binary Palindromeso that it recognizes nested quotes instead of binary palindromes.

Our pushdown automaton works because when it encounters a token, it both pushes the token onto the stack and compares it to the top of the stack and pops it off if it matches. It forks itself each time, so it consumes exponential space and time. But it does work.

And that shows us that pushdown automata are more powerful than deterministic pushdown automata, because they can recognize languages that deterministic pushdown automata cannot recognize: Context-free languages.

deterministic context-free languages are context-free languages

Pushdown automata are a more powerful generalization of deterministic pushdown automata: They can recognize anything a deterministic pushdown automaton can recognize, and using the exact same diagram.

We can see this by writing a pushdown automaton to recognize a deterministic context-free language. Here is the state diagram:

And here is our code. As noted before, in our implementation, it is almost identical to the implementation we would write for a DPA:

class LOL extends PushdownAutomaton {

* start (token) {

if (token === 'L') {

yield this

.fork()

.transitionTo('l');

}

}

* l (token) {

if (token === 'O') {

yield this

.fork()

.transitionTo('lo');

}

}

* lo (token) {

if (token === 'L') {

yield this

.fork()

.transitionTo('lol');

}

}

* lol (token) {

if (token === 'O') {

yield this

.fork()

.transitionTo('lo');

}

if (token === END) {

yield this

.fork()

.recognize();

}

}

}

test(LOL, [

'', 'L', 'LO', 'LOL', 'LOLO',

'LOLOL', 'LOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOL',

'TROLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLO'

]);

//=>

'' => false

'L' => false

'LO' => false

'LOL' => true

'LOLO' => false

'LOLOL' => true

'LOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLOL' => true

'TROLOLOLOLOLOLOLOLO' => false

But we needn’t ask anyone to “just trust us on this.” Here’s an implementation of PushdownAutomaton that works for both deterministic and general pushdown automata:

class PushdownAutomaton {

constructor(internal = 'start', external = []) {

this.internal = internal;

this.external = external;

this.halted = false;

this.recognized = false;

}

isDeterministic () {

return false;

}

push(token) {

this.external.push(token);

return this;

}

pop() {

this.external.pop();

return this;

}

replace(token) {

this.external[this.external.length - 1] = token;

return this;

}

top() {

return this.external[this.external.length - 1];

}

hasEmptyStack() {

return this.external.length === 0;

}

transitionTo(internal) {

this.internal = internal;

return this;

}

recognize() {

this.recognized = true;

return this;

}

halt() {

this.halted = true;

return this;

}

consume(token) {

const states = [...this[this.internal](token)];

if (this.isDeterministic()) {

return states[0] || [];

} else {

return states;

}

}

fork() {

return new this.constructor(this.internal, this.external.slice(0));

}

static evaluate (string) {

let states = [new this()];

for (const token of string) {

const newStates = states

.flatMap(state => state.consume(token))

.filter(state => state && !state.halted);

if (newStates.length === 0) {

return false;

} else if (newStates.some(state => state.recognized)) {

return true;

} else {

states = newStates;

}

}

return states

.flatMap(state => state.consume(END))

.some(state => state && state.recognized);

}

}

Now if we want to show that an automaton written in non-deterministic style has the same semantics as an automaton written for our original DeterministicPushdownAutomaton class, we can write it like this:

class LOL extends PushdownAutomaton {

isDeterministic () {

return true;

}

// rest of states remain exactly the same

...

}

We can even experiment with something like BinaryPalindrome. By implementing isDeterministic() and alternating between having it return true and false, we can see that the language it recognizes is context-free but not deterministically context-free:

class BinaryPalindrome extends PushdownAutomaton {

isDeterministic () {

return true;

}

...

}

test(BinaryPalindrome, [

'', '0', '00', '11', '0110',

'1001', '0101', '100111',

'01000000000000000010'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'0' => false

'00' => false

'11' => false

'0110' => false

'1001' => false

'0101' => false

'100111' => false

'01000000000000000010' => false

class BinaryPalindrome extends PushdownAutomaton {

isDeterministic () {

return false;

}

...

}

test(BinaryPalindrome, [

'', '0', '00', '11', '0110',

'1001', '0101', '100111',

'01000000000000000010'

]);

//=>

'' => true

'0' => false

'00' => true

'11' => true

'0110' => true

'1001' => true

'0101' => false

'100111' => false

'01000000000000000010' => true

Now, since context-free languages are the set of all languages that pushdown automata can recognize, and since pushdown automata can recognize all languages that deterministic pushdown automata can recognize, it follows that the set of all deterministic context-free languages is a subset of the set of all context-free languages.

Which is implied by the name, but it’s always worthwhile to explore some of the ways to demonstrate its truth.

The End

summary

We’ve seen that formal languages (those made up of unambiguously defined strings of symbols) come in at least three increasingly complex families, and that one way to quantify that complexity is according to the capabilities of the machines (or “automata”) capable of recognizing strings in the language.

Here are the three families of languages and automata that we reviewed:

| Language Family | Automata Family | Example Language(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Regular | Finite State | Binary Numbers, LOL |

| Deterministic Context-free | Deterministic Pushdown | Balanced Parentheses |

| Context-free | Pushdown | Palindromes |

An obvious question is, Do you need to know the difference between a regular language and a context-free language if all you want to do is write some code that recognizes balanced parentheses?

The answer is, Probably not. Consider cooking. A food scientist knows all sorts of things about why certain recipes do what they do. A chef de cuisine (or “chef”) knows how to cook and improvise recipes. Good chefs end up acquiring a fair bit of food science in their careers, and they know how to apply it, but they spend most of their time cooking, not thinking about what is going on inside the food when it cooks.

There are some areas where at least a smattering of familiarity with this particular subject is helpful. Writing parsers, to give one example. Armed with this knowledge, and but little more, the practising programmer knows how to design a configuration file’s syntax or a domain-specific language to be amenable to parsing by an LR(k) parser, and what implications deviating from a deterministic context-free language will have on the performance of the parser.

But on a day-to-day basis, if asked to recognize balanced parentheses?

The very best answer is probably /^(?'balanced'(?:\(\g'balanced'\))*)$/x for those whose tools support recursive regular expressions, or a simple loop with a counter or a stack.

*Detail of Robarts Library © 2006 Andrew Louis. Used with permission, all rights reserved.

further reading

If you enjoyed reading this introduction to formal languages and automata that recognize them, here are some interesting avenues to pursue:

Formal languages are actually specified with formal grammars, not with informal descriptions like “palindrome,” or, “binary number.” The most well-known formal grammar is the regular grammar, which defines a regular language. Regular grammars begat the original regular expressions.

Balanced parentheses has been discussed in this blog before: Pattern Matching and Recursion discusses building a recognizer out of composeable pattern-matching functions, while Alice and Bobbie and Sharleen and Dyck discusses a cheeky little solution to the programming problem.

For those comfortable with code examples written in Ruby, the general subject of ideal computing machines and the things they can compute is explained brilliantly and accessibly in Tom Stuart’s book Understanding Computation.

a bonus problem

Enthusiastic readers can try their hand at writing a function or generator that prints/generates all possible valid balanced parentheses strings. Yes, such a function will obviously run to infinity if left unchecked, a generator will be easier to work with.

The main thing to keep in mind is that such a generator must be arranged so that every finite balanced parentheses string must be output after a finite number of iterations. The following pseudo-code will not work:

function * balanced () {

yield ''; // the only valid string with no top-level pairs

for (let p = 0, true; ++p) {

// yield every balanced parentheses string with p top-level parentheses

}

}

A generator function written with this structure would first yield an infinite number of strings with a single top-level pair of balanced parentheses, e.g. (), (()), ((())), (((()))), .... Therefore, strings like ()() and ()()(), which are both valid, would not appear within a finite number of iterations.

It’s an interesting exercise, and very much related to grammars and production rules.

discussions

Discuss this essay on hacker news, proggit, or /r/javascript.

Notes

-

Formal regular expressions were invented by Stephen Kleene. ↩

-

There are many ways to write DFAs in JavaScript. In How I Learned to Stop Worrying and ❤️ the State Machine, we built JavaScript programs using the state pattern, but they were far more complex than a deterministic finite automaton. For example, those state machines could store information in properties, and those state machines had methods that could be called.

Such “state machines” are not “finite” state machines, because in principle they can have an infinite number of states. They have a finite number of defined states in the pattern, but their properties allow them to encode state in other ways, and thus they are not finite state machines. ↩ -

To demonstrate that “If there are a finite number of strings in a language, there must be a DFA that recognizes that language,” take any syntax for defining a DFA, such as a table. With a little thought, one can imagine an algorithm that takes as its input a finite list of acceptable strings, and generates the appropriate table. ↩

-

This type of proof is known as “Reductio Ad Absurdum,” and it is a favourite of logicians, because quidquid Latine dictum sit altum videtur. ↩

-

An interesting thing to note is for any DFA, there must be an infinite number of pairs of different strings that lead to the same state, this follows form the fact that the DFA has a finite number of states, but we can always find more finite strings than there are states in the DFA.

But for this particular case, where we are talking about strings that consist of a single symbol, and of different lengths, it follows that the DFA must contain at least one loop. ↩ -

No matter how a machine is organized, if it has a finite number of states, it cannot recognized balanced parenthese by our proof above. Fr example, if we modify our DFA to allow an on/off flag for each state, and we have a finite number of states, our machine is not more powerful than a standard DFA, it is just more compact: Its definition is

log2the size of a standard DFA, but it still has a finite number of possible different states. ↩ -

For this pattern, we are not interested in properly typeset quotation marks, we mean the single and double quotes that don’t have a special form for opening and closing, the kind you find in programming languages that were designed to by reproducible by telegraph equipment:

'and". If we could use the proper “quotes,” then our language would be a Dyck Language, equivalent to balanced parentheses. ↩ -

The even-length palindrome language composes of

0s and1s is 100% equivalent to the nested quotes language, we’re just swapping0for', and1for", because they’re easier for this author’s eyes to read. ↩ -

In concatenative programming languages, such as PostScript, Forth, and Joy, there are

DUPandSWAPoperations that, when used in the right combination, can bring an element of the stack to the top, and then put it back where it came from. One could construct a DPA such that it has the equivalent ofDUPandSWAPoperations, but since a DPA can only perform onepush,pop, orreplacefor each token it consumes, the depth of stack it can reach is limited by its ability to store the tokens it is consuming in its internal state, which is finite. For any DPA, there will always be some depth of stack that is unreachable without discarding information. ↩ -

If we were really strict about OO and inheritance, we might have them both inherit from a common base class of

AbstractPushdownAutomaton, but “Aint nobody got time for elaborate class hierarchies.” ↩ -

This code makes a number of unnecessary copies of states, we could devise a scheme to use structural sharing and copy-on-write semantics, but we don’t want to clutter up the basic idea right now. ↩