“Any sufficiently complicated model class contains an ad-hoc, informally-specified, bug-ridden, slow implementation of half of a state machine.”–former colleague1

Domain models are representations of meaningful real-world concepts pertinent to a sphere of knowledge, influence or activity (the “domain”) that need to be modelled in software. Domain models can represent concrete real-word objects, or more abstract things like meetings and incidents.

My colleague’s insight was that most domain models end up having a representation of various states. Over time, they build up a lot of logic around how and when they transition between these states, and that logic is smeared across various methods where it becomes difficult to understand and modify.

By recognizing when domain models should be represented first and foremost as state machines–or recognizing when to refactor domain models into state machines–we keep our models understandable and workable. We tame their complexity.

So, what are state machines? And how do they help?

finite state machines

A finite state machine, or simply a state machine, is a mathematical model of computation. It is an abstract machine that can be in exactly one of a finite number of states at any given time.

A state machine can change from one state to another in response to some external inputs; the change from one state to another is called a transition. A state machine is defined by a list of its states, its initial state, and the conditions for each transition.–Wikipedia

Well, that’s a mouthful. To put it in context from a programming (as opposed to idealized model of computation) point of view, when we program with objects, we build little machines. They have internal state and respond to messages or events from the rest of the program via the mechanism of their methods. (JavaScript also permits direct access to properties, but let’s consider the subset of programs that only interact with objects via methods.)

Most objects are designed to encapsulate some kind of state. Stateless objects are certainly a thing, but let’s put them aside and consider only objects that have state. Some such objects can be considered State Machines, some cannot. What distinguishes them?

First, a state machine has a notion of a state. All stateful objects have some kind of “state,” but a state machine reifies this and gives it a name. Furthermore, there are a finite number of possible states that a state machine can be in, and it is always in exactly one of these states.

For example let’s say that a bank account has a balance and it can be be one of open or closed. Its balance certainly is stateful, but it’s “state” from the perspective of a state machine is either open or closed.

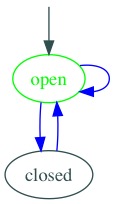

Second, a state machine formally defines a starting state, and allowable transitions between states. The aforementioned bank account starts in open state. It can transition from open to closed, and from time to time, from closed back to open. Sometimes, it transitions from a state back to itself, which we see in an arrow from open back to open. This can be displayed with a diagram, and such diagrams are a helpful way to document or brainstorm behaviour:

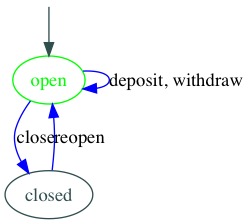

Third, a state machine transitions between states in response to events. Our bank account starts in open state. When open, a bank account responds to a close event by transitioning to the closed state. When closed, a bank account responds to the reopen event by transitioning to the open state. As noted, some transitions do not involve changes in state. When open, a bank account responds to deposit and withdraw events, and it transitions back to open state.

transitions

The events that trigger transitions are noted by labeling the transitions on the diagram:

We now have enough to create a naïve JavaScript object to represent what we know so far about a bank account. We will make each event a method, and the state will be a string:

let account = {

state: 'open',

balance: 0,

deposit (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.balance = this.balance + amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

withdraw (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.balance = this.balance - amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

close () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this.state = 'closed';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

reopen () {

if (this.state === 'closed') {

// ...restore balance if applicable

this.state = 'open';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

}

}

account.state

//=> open

account.close();

account.state

//=> closed

The first thing we observe is that our bank account handles different events in different states. In the open state, it handles the deposit, withdraw, and close event. In the closed state, it only handles the reopen event. The natural way of implementing events is as methods on the object, but now we are imbedding in each method a responsibility for knowing what state the account is in and whether that transition can be allowed or not.

It’s also not clear from the code alone what all the possible states are, or how we transition. What is clear is what each method does, in isolation. This is one of the “affordances” of a typical object-with-methods design: It makes it very easy to see what an individual method does, but not to get a higher view of how the methods are related to each other.

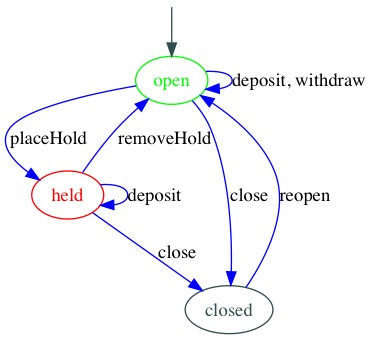

Let’s add a little functionality: A “hold” can be placed on accounts. Held accounts can accept deposits, but not withdrawals. And naturally, the hold can be removed. The new diagram looks like this:

And the code we end up with looks like this:

let account = {

state: 'open',

balance: 0,

deposit (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open' || this.state === 'held') {

this.balance = this.balance + amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

withdraw (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.balance = this.balance - amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

placeHold () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.state = 'held';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

removeHold () {

if (this.state === 'held') {

this.state = 'open';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

close () {

if (this.state === 'open' || this.state === 'held') {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this.state = 'closed';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

reopen () {

if (this.state === 'closed') {

// ...restore balance if applicable

this.state = 'open';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

}

}

To accomodate the new state, we had to update a number of different methods. This is not difficult when the requirements are in front of us, and it’s often a mistake to overemphasize whether it is easy or difficult to implement something when the requirements and the code are both well-understood.

However, we can see that the code does not do a very good job of documenting what is or isn’t possible for a held account. This organization makes it easy to see exactly what a deposit or withdraw does, at the expense of making it easy to see how held accounts work or the overall flow of accounts from state to state.

If we wanted to emphasize states, what could we do?

executable state descriptions

Directly compiling diagrams has been–so far–highly unproductive for programming. But there’s another representation of a state machine that can prove helpful: A transition table. Here’s our transition table for the naïve bank account:

| open | held | closed | |

|---|---|---|---|

| open | deposit, withdraw | placeHold | close |

| held | removeHold | deposit | close |

| closed | reopen |

In the leftmost column, we have the current state of the account. Each subsequent column is a destination state. At the intersection of the current state and a destination state, we have the event or events that transition the object from current to destination state. Thus, deposit and withdraw transition from open to open, while placeHold transitions the object from open to held. The start state is arbitrarily taken as the first state listed.

Like the state diagram, the transition table shows clearly which events are handled by which state, and the transitions between them. We can take this idea to our executable code: Here’s a version of our account that uses objects to represent table rows and columns.

const STATES = Symbol("states");

const STARTING_STATE = Symbol("starting-state");

const Account = {

balance: 0,

STARTING_STATE: 'open',

STATES: {

open: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

},

held: {

placeHold () {}

},

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

}

},

held: {

open: {

removeHold () {}

},

held: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; }

},

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

}

},

closed: {

open: {

reopen () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

}

}

}

}

};

This description isn’t executable, but it doesn’t take much to write an implementation organized along the same lines:

implementing a state machine that matches our description

In Mixins, Forwarding, and Delegation in JavaScript, we briefly touched on using late-bound delegation to create state machines. The principle is that instead of using strings for state, we’ll use objects that contain the methods we’re interested in. First, we’ll write out what those objects will look like:

const STATE = Symbol("state");

const STATES = Symbol("states");

const open = {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

placeHold () {

this[STATE] = this[STATES].held;

},

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this[STATE] = this[STATES].closed;

}

};

const held = {

removeHold () {

this[STATE] = this[STATES].open;

},

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this[STATE] = this[STATES].closed;

}

};

const closed = {

reopen () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

this[STATE] = this[STATES].open;

}

};

Now our actual account object stores a state object rather than a state string, and delegates all methods to it. When an event is invalid, we’ll get an exception. That can be “fixed,” but let’s not worry about it now:

const account = {

balance: 0,

[STATE]: open,

[STATES]: { open, held, closed },

deposit (...args) { return this[STATE].deposit.apply(this, args); },

withdraw (...args) { return this[STATE].withdraw.apply(this, args); },

close (...args) { return this[STATE].close.apply(this, args); },

placeHold (...args) { return this[STATE].placeHold.apply(this, args); },

removeHold (...args) { return this[STATE].removeHold.apply(this, args); },

reopen (...args) { return this[STATE].reopen.apply(this, args); }

};

Unfortunately, this regresses: We’re littering the methods with state assignments. One of the benefits of transition tables and state diagrams is that they communicate both the from_and _to states of each transition. Assigning state within methods does not make this clear, and introduces an opportunity for error.

To fix this, we’ll write a transitionsTo decorator to handle the state changes.2

const STATE = Symbol("state");

const STATES = Symbol("states");

function transitionsTo (stateName, fn) {

return function (...args) {

const returnValue = fn.apply(this, args);

this[STATE] = this[STATES][stateName];

return returnValue;

};

}

const open = {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

placeHold: transitionsTo('held', () => undefined),

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

};

const held = {

removeHold: transitionsTo('open', () => undefined),

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

};

const closed = {

reopen: transitionsTo('open', function () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

})

};

const account = {

balance: 0,

[STATE]: open,

[STATES]: { open, held, closed },

deposit (...args) { return this[STATE].deposit.apply(this, args); },

withdraw (...args) { return this[STATE].withdraw.apply(this, args); },

close (...args) { return this[STATE].close.apply(this, args); },

placeHold (...args) { return this[STATE].placeHold.apply(this, args); },

removeHold (...args) { return this[STATE].removeHold.apply(this, args); },

reopen (...args) { return this[STATE].reopen.apply(this, args); }

};

Now we have made it quite clear which methods belong to which states, and which states they transition to.

We could stop right here if we wanted to: This is a pattern that is remarkably easy to write by hand, and for many cases, it is far easier to read and maintain than having various if and/or switch statements littering every method. But since we’re enjoying ourselves, what would it take to automate the process of implementing this naïve state machine pattern from descriptions?

compiling descriptions into state machines

Code that writes code does add a certain complexity, but it also enables us to arrange our code such that it is organized more appropriately for our problem domain. Managing stateful entities is one of the hardest problems in programming3, so it’s often worth investing in a little infrastructure work to arrive at an easier to understand and extend program.

The first thing we’ll do is “begin with the end in mind.” We wish to be able to write something like this:

const STATES = Symbol("states");

const STARTING_STATE = Symbol("starting-state");

function transitionsTo (stateName, fn) {

return function (...args) {

const returnValue = fn.apply(this, args);

this[STATE] = this[STATES][stateName];

return returnValue;

};

}

const account = StateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[STATES]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

placeHold: transitionsTo('held', () => undefined),

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

held: {

removeHold: transitionsTo('open', () => undefined),

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

closed: {

reopen: transitionsTo('open', function () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

})

}

}

});

What does StateMachine do?

const RESERVED = [STARTING_STATE, STATES];

function StateMachine (description) {

const machine = {};

// Handle all the initial states and/or methods

const propertiesAndMethods = Object.keys(description).filter(property => !RESERVED.includes(property));

for (const property of propertiesAndMethods) {

machine[property] = description[property];

}

// now its states

machine[STATES] = description[STATES];

// what event handlers does it have?

const eventNames = Object.entries(description[STATES]).reduce(

(eventNames, [state, stateDescription]) => {

const eventNamesForThisState = Object.keys(stateDescription);

for (const eventName of eventNamesForThisState) {

eventNames.add(eventName);

}

return eventNames;

},

new Set()

);

// define the delegating methods

for (const eventName of eventNames) {

machine[eventName] = function (...args) {

const handler = this[STATE][eventName];

if (typeof handler === 'function') {

return this[STATE][eventName].apply(this, args);

} else {

throw `invalid event ${eventName}`;

}

}

}

// set the starting state

machine[STATE] = description[STATES][description[STARTING_STATE]];

// we're done

return machine;

}

let’s summarize

We began with this simple code for a bank account that behaved like a state machine:

let account = {

state: 'open',

close () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this.state = 'closed';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

reopen () {

if (this.state === 'closed') {

// ...restore balance if applicable

this.state = 'open';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

}

};

Encumbering this simple example with meta-programming to declare a state machine may not have been worthwhile, so we won’t jump to the conclusion that we ought to have written it differently. However, code being code, requirements were discovered, and we ended up writing:

let account = {

state: 'open',

balance: 0,

deposit (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.balance = this.balance + amount;

} else if (this.state === 'held') {

this.balance = this.balance + amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

withdraw (amount) {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.balance = this.balance - amount;

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

placeHold () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

this.state = 'held';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

removeHold () {

if (this.state === 'held') {

this.state = 'open';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

close () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this.state = 'closed';

}

if (this.state === 'held') {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

this.state = 'closed';

} else {

throw 'invalid event';

}

},

reopen () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

throw 'invalid event';

} else if (this.state === 'closed') {

// ...restore balance if applicable

this.state = 'open';

}

}

}

Faced with more complexity, and the dawning realization that things are going to inexorably become more complex over time, we refactored our code from an ad-hoc, informally-specified, bug-ridden, slow implementation of half of a state machine to this example:

const account = StateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[STATES]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

placeHold: transitionsTo('held', () => undefined),

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

held: {

removeHold: transitionsTo('open', () => undefined),

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

closed: {

reopen: transitionsTo('open', function () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

})

}

}

});

how does this help?

Let’s finish our examination of state machines with a small change. We wish to add an availableToWithdraw method. It returns the balance (if positive and for accounts that are open and not on hold). The old way would be to write a single method with an if statement:

let account = {

// ...

availableToWithdraw () {

if (this.state === 'open') {

return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0;

} else if (this.state === 'held') {

return 0;

} else {

throw 'invalid method';

}

}

}

As discussed, this optimizes for understanding availableToWithdraw, but makes it harder to understand how open and held accounts differ from each other. It combines multiple responsibilities in the availableToWithdraw method: Understanding everything about account states, and implementing the functionality for each of the applicable states.

The “state machine way” is to write:

const account = StateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[STATES]: {

open: {

// ...

availableToWithdraw () { return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0; }

},

held: {

// ...

availableToWithdraw () { return 0; }

}

}

});

This emphasizes the different states and the characteristics of an account in each state, and it separates the responsibilities: States and transitions are handled by our “state machine” organization, and each of the two functions handles just the mechanics of reporting the correct amount available for withdrawal.

“So much complexity in software comes from trying to make one thing do two things.”–Ryan Singer

We can obviously extend our code to generate ES2015 classes, incorporate before- and after- method decorations, tackle validating models in general and transitions in particular, and so forth. Our code here was written to illustrate the basic idea, not to power the next Startup Unicorn.

But for now, our lessons are:

-

It isn’t always necessary to build architecture to handle every possible future requirement. But it is a good idea to recognize that as the code grows and evolves, we may wish to refactor to the correct choice in the future. While we don’t want to do it too early, we also don’t want to do it too late.

-

Organizing things that behave like state machines along state machine lines separates responsibilities and decomposes methods into smaller pieces, each of which is focused on implementing the correct behaviour for a single state.

(discuss on hacker news, /r/programming, /r/javascript, or edit this page)

New!: More State Machine ❤️: From Reflection to Statecharts

p.s. State was popularized as one of the twenty-three design patterns articulated by the “Gang of Four.” The implementation examples tend to be somewhat specific to a certain style of OOP language, but it is well-worth a review.

javascript allongé, the six edition

If you enjoyed this essay, you’ll ❤️ JavaScript Allongé, the Six Edition. It’s 100% free to read online!

notes

-

My colleague may or may not have said those exact words, but they introduced me to the idea of considering domain models as state machines by default, and my understanding has been crisper ever since. ↩

-

At this moment, syntactic sugar for decorators are not yet fully accepted as a JavaScript standard. In this essay we’ll stick with ES2015 syntax, but feel free to use

@transitionsTo('open')syntax if your toolchain supports the proposed syntactic sugar. ↩ -

Programmers are congenitally unable to resist quoting Phil Karlton when they hear the words “hard,” “problem,” and “computer.” Let’s rise above that today. ↩