In “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and ❤️ the State Machine,” we built an extremely basic state machine to model a bank account.

State machines, as we discussed, are a very useful tool for organizing the behaviour of domain models, representations of meaningful real-world concepts pertinent to a sphere of knowledge, influence or activity (the “domain”) that need to be modelled in software.

A state machine is an object, but it has a distinctive “behaviour.” It is always in exactly one of a finite number of states, and its behaviour is determined by its state, right down to what methods it has in each state and which other states a method may or may not transition the state machine to.

This is interesting! So interesting, that we are going to spend a few minutes looking strictly at state machine behaviour, and more specifically, at the interface a state machine has with the entities that use it.

Let’s get started.

our bank account state machine

Here’s a small variation on the “bank account” code we wrote:12

// The naïve state machine extracted from https://raganwald.com/2018/02/23/forde.html

// Modified to use weak maps for "private" state

const STATES = Symbol("states");

const STARTING_STATE = Symbol("starting-state");

const RESERVED = [STARTING_STATE, STATES];

const MACHINES_TO_CURRENT_STATE_NAMES = new WeakMap();

const MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES = new WeakMap();

const MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES = new WeakMap();

function getStateName (machine) {

return MACHINES_TO_CURRENT_STATE_NAMES.get(machine);

}

function getState (machine) {

return MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.get(machine)[getStateName(machine)];

}

function setState (machine, stateName) {

MACHINES_TO_CURRENT_STATE_NAMES.set(machine, stateName);

}

function transitionsTo (stateName, fn) {

return function (...args) {

const returnValue = fn.apply(this, args);

setState(this, stateName);

return returnValue;

};

}

function BasicStateMachine (description) {

const machine = {};

// Handle all the initial states and/or methods

const propertiesAndMethods = Object.keys(description).filter(property => !RESERVED.includes(property));

for (const property of propertiesAndMethods) {

machine[property] = description[property];

}

// now its states

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.set(machine, description[STATES]);

// what event handlers does it have?

const eventNames = Object.entries(MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.get(machine)).reduce(

(eventNames, [state, stateDescription]) => {

const eventNamesForThisState = Object.keys(stateDescription);

for (const eventName of eventNamesForThisState) {

eventNames.add(eventName);

}

return eventNames;

},

new Set()

);

// define the delegating methods

for (const eventName of eventNames) {

machine[eventName] = function (...args) {

const handler = getState(machine)[eventName];

if (typeof handler === 'function') {

return getState(machine)[eventName].apply(this, args);

} else {

throw `invalid event ${eventName}`;

}

}

}

// set the starting state

MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.set(machine, description[STARTING_STATE]);

setState(machine, MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.get(machine));

// we're done

return machine;

}

const account = BasicStateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[STATES]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0; },

placeHold: transitionsTo('held', () => undefined),

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

held: {

removeHold: transitionsTo('open', () => undefined),

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return 0; },

close: transitionsTo('closed', function () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

})

},

closed: {

reopen: transitionsTo('open', function () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

})

}

}

});

(code)

It’s simple, and it seems to work. What’s the problem?

reflecting on state machines

In computer science, reflection is the ability of a computer program to examine, introspect, and modify its own structure and behaviour at runtime.–Wikipedia

Remember we talked about objects exposing their interface? In JavaScript, we can use code to examine the methods a bank account responds to:

function methodsOf (obj) {

const list = [];

for (const key in obj) {

if (typeof obj[key] === 'function') {

list.push(key);

}

}

return list;

}

methodsOf(account)

//=> deposit, withdraw, availableToWithdraw, placeHold, close, removeHold, reopen

This is technically correct, because we wrote methods that delegated all of these “events” to the current state. But this is semantically wrong, because the whole idea behind a state machine is that the methods it responds to vary according to what state it is in.

For example, when an object is created, it is in ‘open’ state, and placehold, removeHold, and reopen are all invalid methods. Our interface is lying to the outside world about what methods the object truly supports. This is an artefact of our design: We chose to implement methods, but then throw invalid method if an object in a particular state was not supposed to respond to a particular event.

The ideal would be for it not to have these methods at all, so that the standard way that we use our programming language to determine whether an object responds to a method–testing for a member that is a function–just works.

One way to go about this is to replace all the delegation methods with prototype mongling. First, the new setState method:3

function setState (machine, stateName) {

MACHINES_TO_CURRENT_STATE_NAMES.set(machine, stateName);

Object.setPrototypeOf(machine, getState(machine));

}

Now we can remove all the code that writes the delegation methods:

function RefectiveStateMachine (description) {

const machine = {};

// Handle all the initial states and/or methods

const propertiesAndMethods = Object.keys(description).filter(property => !RESERVED.includes(property));

for (const property of propertiesAndMethods) {

machine[property] = description[property];

}

// now its states

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.set(machine, description[STATES]);

// set the starting state

MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.set(machine, description[STARTING_STATE]);

setState(machine, MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.get(machine));

// we're done

return machine;

}

How well does it work? Let’s try it with account = ReflectiveStateMachine({ ... }) more-or-less as before:

methodsOf(account)

//=> deposit, withdraw, availableToWithdraw, placeHold, close

account.placeHold()

methodsOf(account)

//=> removeHold, deposit, availableToWithdraw, close

(code)

Now we have a state machine that correctly exposes the shallowest part of its interface, the methods that it responds to at any one time. What else might other code be interested in? And why?

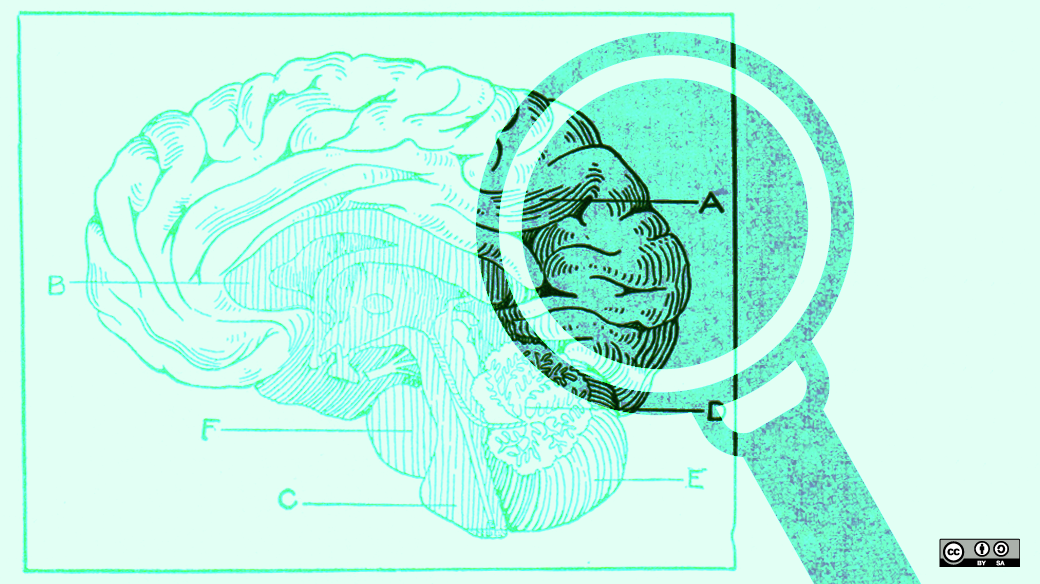

descriptions and diagrams for code

Two things have been proven to be consistently true since the dawn of human engineering:

- Using a diagram, schematic, blueprint, or other symbolic representation of work to be done helps us plan our work, do our work, verify that our work is correctly done, and understand our work.

- Diagrams, schematics, blueprints, and other symbolic representations of work invariably drift from the work over time, until their inaccuracies present more harm than good.

This is especially true of programming, where change happens rapidly and “documentation” lags woefully behind. In early days, researchers toyed with various ways of making executable diagrams for programs: Humans would draw a diagram that communicated the program’s behaviour, and the computer would interpret it directly.

Another approach has been to dynamically generate diagrams and comments of one form or another. Many modern programming frameworks can generate documentation from the source code itself, sometimes using special annotations as a kind of markup. The value of this approach is that when the code changes, so does the documentation.

Can we generate state transition diagrams from our source code?

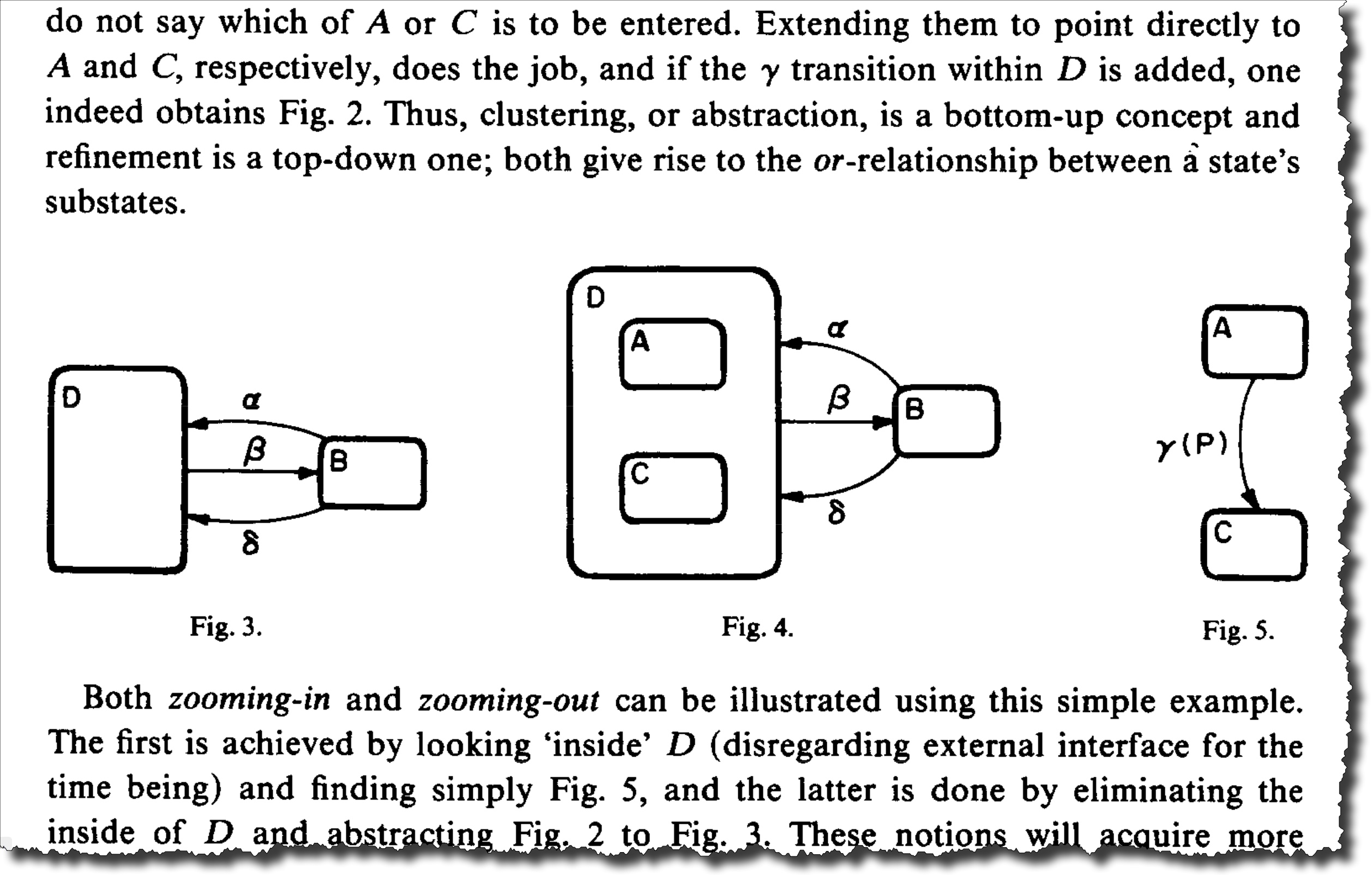

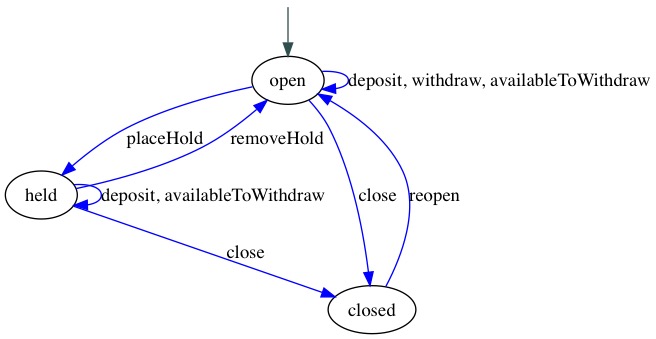

Well, we’re not going to write an entire graphics generation engine, although that would be a pleasant diversion. But what we will do is generate a kind of program that another engine can consume to produce our documentation. The diagrams in How I Learned to Stop Worrying and ❤️ the State Machine were generated with Graphviz, free software that generates graphs specified with the DOT graph description language.

The dot file to generate the transition graph for our bank account looks like this:

digraph Account {

start [label="", fixedsize="false", width=0, height=0, shape=none];

start -> open [color=darkslategrey];

open;

open -> open [color=blue, label="deposit, withdraw, availableToWithdraw"];

open -> held [color=blue, label="placeHold"];

open -> closed [color=blue, label="close"];

held;

held -> held [color=blue, label="deposit, availableToWithdraw"];

held -> open [color=blue, label="removeHold"];

held -> closed [color=blue, label="close"];

closed;

closed -> open [color=blue, label="reopen"];

}

We could generate this DOT file if we have a list of states, events, and the states those events transition to. Getting a list of states and events is easy. But what we don’t have is the starting state, nor do we have the states these methods (a/k/a “events”) transition to.

We could easily store the starting state for each state machine in a weak map. But what to do about the transitions? This is a deep problem. Throughout our programming explorations, we have repeatedly feasted on JavaScript’s ability for functions to consume other functions as arguments and return new functions. Using this, we have written many different kinds of decorators, including transitionsTo.

The beauty of functions returning functions is that closures form a hard encapsulation: The closure wrapping a function is available only functions created within its scope, not to any other scope. The drawback is that when we want to do some inspection, we cannot pierce the closure. We simply cannot tell from the function that transitionsTo returns what state it will transition to.

We have a few options. One is to use a different form of description that encodes the destination states without a transitionsTo function.

a new-old kind of notation for bank accounts

When we first formulated a notation for state machines, we considered a more declarative format that encoded states and transitions using nested objects. It looked a little like this:

const TRANSITIONS = Symbol("transitions");

const STARTING_STATE = Symbol("starting-state");

const account = TransitionOrientedStateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[TRANSITIONS]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0; },

held: {

placeHold () {}

},

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

}

},

held: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return 0; },

open: {

removeHold () {}

},

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

}

},

closed: {

open: {

reopen () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

}

}

}

}

});

This is touch more verbose, but we can write a StateMachine to do all the interpretation work. It will keep the description but translate the methods to use transitionsTo for us:

const MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS = new WeakMap();

function TransitionOrientedStateMachine (description) {

const machine = {};

// Handle all the initial states and/or methods

const propertiesAndMethods = Object.keys(description).filter(property => !RESERVED.includes(property));

for (const property of propertiesAndMethods) {

machine[property] = description[property];

}

// set the transitions for later reflection

MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.set(machine, description[TRANSITIONS]);

// create its top-level state prototypes

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.set(machine, Object.create(null));

for (const state of Object.keys(MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.get(machine))) {

const stateObject = Object.create(null);

const stateDescription = MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.get(machine)[state];

const nonTransitioningMethods = Object.keys(stateDescription).filter(name => typeof stateDescription[name] === 'function');

const destinationStates = Object.keys(stateDescription).filter(name => typeof stateDescription[name] !== 'function');

for (const nonTransitioningMethodName of nonTransitioningMethods) {

const nonTransitioningMethod = stateDescription[nonTransitioningMethodName];

stateObject[nonTransitioningMethodName] = nonTransitioningMethod;

}

for (const destinationState of destinationStates) {

const destinationStateDescription = stateDescription[destinationState];

const transitioningMethodNames = Object.keys(destinationStateDescription).filter(name => typeof destinationStateDescription[name] === 'function');

for (const transitioningMethodName of transitioningMethodNames) {

const transitioningMethod = destinationStateDescription[transitioningMethodName];

stateObject[transitioningMethodName] = transitionsTo(destinationState, transitioningMethod);

}

}

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.get(machine)[state] = stateObject;

}

// set the starting state

MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.set(machine, description[STARTING_STATE]);

setState(machine, MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.get(machine));

// we're done

return machine;

}

And now we can write a getTransitions function that extracts the structure of the transitions:

function getTransitions (machine) {

const description = { [STARTING_STATE]: MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.get(machine) };

const transitions = MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.get(machine);

for (const state of Object.keys(transitions)) {

const stateDescription = transitions[state];

description[state] = Object.create(null);

const selfTransitions = [];

for (const descriptionKey of Object.keys(stateDescription)) {

const innerDescription = stateDescription[descriptionKey];

if (typeof innerDescription === 'function' ) {

selfTransitions.push(descriptionKey);

} else {

const destinationState = descriptionKey;

const transitionEvents = Object.keys(innerDescription);

description[state][destinationState] = transitionEvents;

}

}

if (selfTransitions.length > 0) {

description[state][state] = selfTransitions;

}

}

return description;

}

getTransitions(account)

//=> {

open: {

open: ["deposit", "withdraw", "availableToWithdraw"],

held: ["placeHold"],

closed: ["close"]

},

held: {

open: ["removeHold"],

held: ["deposit", "availableToWithdraw"],

closed: ["close"]

},

closed: {

open: ["reopen"]

},

Symbol(starting-state): "open"

}

🎉‼️

With getTransitions in hand, we’re ready to generate a DOT file from the symbolic description:

function dot (machine, name) {

const transitionsForMachine = getTransitions(machine);

const startingState = transitionsForMachine[STARTING_STATE];

const dot = [];

dot.push(`digraph ${name} {`);

dot.push('');

dot.push(' start [label="", fixedsize="false", width=0, height=0, shape=none];');

dot.push(` start -> ${startingState} [color=darkslategrey];`);

for (const state of Object.keys(transitionsForMachine)) {

dot.push('');

dot.push(` ${state}`);

dot.push('');

const stateDescription = transitionsForMachine[state];

for (const destinationState of Object.keys(stateDescription)) {

const events = stateDescription[destinationState];

dot.push(` ${state} -> ${destinationState} [color=blue, label="${events.join(', ')}"];`);

}

}

dot.push('}');

return dot.join("\r");

}

dot(account, "Account")

//=>

digraph Account {

start [label="", fixedsize="false", width=0, height=0, shape=none];

start -> open [color=darkslategrey];

open

open -> open [color=blue, label="deposit, withdraw, availableToWithdraw"];

open -> held [color=blue, label="placeHold"];

open -> closed [color=blue, label="close"];

held

held -> open [color=blue, label="removeHold"];

held -> held [color=blue, label="deposit, availableToWithdraw"];

held -> closed [color=blue, label="close"];

closed

closed -> open [color=blue, label="reopen"];

}

}

(code)

We can feed this .dot file to Graphviz, and it will produce the image we see right in this blog post, and that’s exactly how it was generated:

So. We now have a way of drawing state transition diagrams for state machines. Being able to extract the semantic structure of an object–like the state transitions for a state machine–is a useful kind of reflection, and one that exists at a higher semantic level than simply reporting on things like the methods an object responds to or the properties it has.

should a state machine hide the fact that it’s a state machine?

People talk about information hiding as separating the responsibility for an object’s “implementation” from its “interface.” The question here is whether an object’s states, transitions between states, and methods in each state are part of its implementation, or whether they are part of its interface, its contracted behaviour.

One way to tell is to ask ourselves whether changing those things will break other code. If we can change the transitions of a state machine without changing any other code in an app, it’s fair to say that the transitions are “just implementation details,” Just as changing a HashMap class to use a Cuckoo Hash instead of a Hash Table doesn’t require us to change any of the code that interacts with our HashMap.

So how about our bank accounts? Consider the following sequence:

account.availableToWithdraw()

//=> 0

account.deposit(42);

account.availableToWithdraw()

//=> ???

Does the second .availableToWithdraw() return forty-two? Or zero? That depends upon whether the account is open or held, and that isn’t a private secret that only the account knows about. We know this, because people openly talk about whether accounts are open, held, or closed. People build processes around the account’s state, and it’s certainly part of the account’s design that the .placeHold method transitions an account into held state.

From this, we get that accounts should certainly behave like state machines. And from that, it’s reasonable that other pieces of code ought to be able to dynamically inspect an account’s current state, as well as its complete graph of states and transitions. That’s as much a part of its public interface as any particular method.4

It follows that in addition to our ReflectiveStateMachine function, we ought to also make both getTransitions and getStateName “public” functions that every other entity can interact with. setState, on the other hand, is best left as a “private” function: To preserve the proper business logic, other entities should invoke methods that perform the appropriate transitions, not directly change state.

We can even create public functions like:

function isStateMachine (object) {

return MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.has(object);

}

So, now we have an understanding of a state machine, the behaviour it contractually guarantees, and how it might be organized such that it can expose its contract dynamically to other code.

But speaking of behaviour…

it’s never as simple as it seems in a blog post

One of the reasons we don’t see as many explicit state machines “in the wild” as we’d expect is that there is a perception that state machines are great when we’ve performed an exhaustive “Big Design Up Front” analysis, and have perfectly identified all of the states and transitions.

Many programmers believe that in a more agile, incremental process, we’re constantly discovering requirements and methods. We may not know that we have a state machine until later in the process, and things being messy, a domain model may not fit neatly into the state machine model even if it appears to have states.

For example, instead of being told that a bank account might be open, held, or closed, we might be told something different:

- A bank account is either open or closed;

- An open bank account is either held or not held;

So now we are told that an account doesn’t have one single state, it has two flags: open/closed and held/not-held. That doesn’t fit the state machine model at all, and refactoring it into open/held/closed may not be appropriate. This is an extremely simple example, but impedance mismatches like this are common, and over time a model may accrete a half-dozen or more toggles and enumerations that represent little states within the domain model’s larger state.

This is maddening, because we know how to model open/closed as a state machine, and if we didn’t have to worry about closed accounts, we also know how to model held/not-held as a state machine.

What to do?

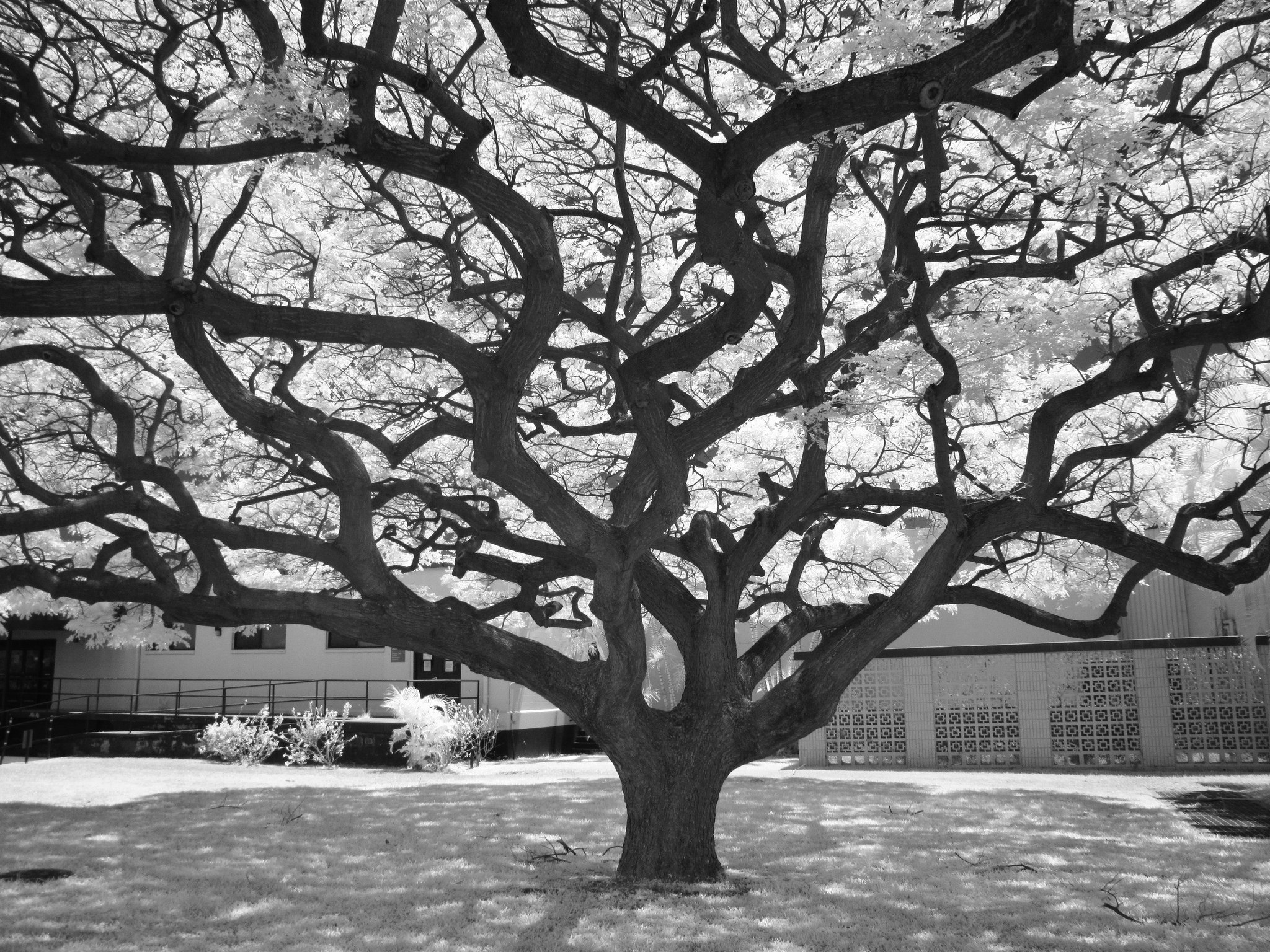

i heard you liked state machines, so…

If we look at a bank account as having two flags, and between their possible settings there are three valid states, we don’t see a state machine. We see a stateful object. But hidden in our implementation is a clue as to how we can solve this semantically.

As implemented, state machines are objects that delegate their behaviour to a state object. There’s one state object for each possible state.

The state object for closed state has just one method, reopen. Our problem with the state object for open state is that it has two different behaviours, depending on whether the account is held or not-held.

That sounds very familiar!

What we are describing is that a bank account has two states. One of them, closed, is a simple object. But the other, open, is itself a state machine! It has two states, held, and not-held.

If we allow state object to be state machines, we can actually model our bank account exactly as our business users describe it.

But first, we’re going to need a bigger notation.5

a bigger notation for state machines

Let’s look at what we want to model. For starters, we want an account that has open and closed states, and we want to describe what is guaranteed to be the case for each state:

const account = HierarchalStateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[TRANSITIONS]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; }

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

}

},

closed: {

open: {

reopen () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

}

}

}

}

});

And if we were thinking about a state machine nested within the open state, it would look like this:

HierarchalStateMachine({

[STARTING_STATE]: 'not-held',

[TRANSITIONS]: {

['not-held']: {

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0; },

held: {

placeHold () {}

}

},

held: {

availableToWithdraw () { return 0; },

['not-held']: {

removeHold () {}

}

}

});

It’s a state machine with two states. In not-held, it supports withdraw, availableToWithdraw, and placewHold. In held, it supports availableToWithdraw and removeHold. It does not need support deposit, because our top-level state machine does that.

So now, we need a way to put the second notation inside the first notation, perhaps like this:

const INNER = Symbol("inner");

const account = HierarchalStateMachine({

balance: 0,

[STARTING_STATE]: 'open',

[TRANSITIONS]: {

open: {

deposit (amount) { this.balance = this.balance + amount; },

closed: {

close () {

if (this.balance > 0) {

// ...transfer balance to suspension account

}

}

},

[INNER]: {

[STARTING_STATE]: 'not-held',

[TRANSITIONS]: {

['not-held']: {

withdraw (amount) { this.balance = this.balance - amount; },

availableToWithdraw () { return (this.balance > 0) ? this.balance : 0; },

held: {

placeHold () {}

}

},

held: {

availableToWithdraw () { return 0; },

['not-held']: {

removeHold () {}

}

}

}

}

},

closed: {

open: {

reopen () {

// ...restore balance if applicable

}

}

}

}

});

using prototypical inheritance to model hierarchal state machines

Here’s what we want to happen: When an account enters open state, as per usual, its prototype will be set to its open state object. That will have a deposit and close method. But what will the open state object’s prototype be? Ah! That will be the inner state machine that has held and not-held methods. And every time the object enters the open state, the inner state machine will enter the not-held state.

So the prototype chain will look something like this:

account -> open -> open.inner -> open.inner.not-held

If the account is held, it will change to:

account -> open -> open.inner -> open.inner.held

And if it is closed, it will change to:

account -> closed

The first thing we’re going to need is to slightly modify our state machine to take a prototype as an argument, and then make sure that every stateObject we create for it points to that prototype:

function HierarchalStateMachine (description, prototype = Object.prototype) {

// ...

for (const state of Object.keys(MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.get(machine))) {

const stateObject = Object.create(prototype);

// ...

}

// ...

}

Armed with this, we can look for [INNER] in any state description. If we don’t find one, the state is going to be whatever we construct for our stateObject.

But if we do find an [INNER], we will recursively construct a state machine from its description, but have its prototype be the stateObject we have constructed. And our state is going to be the inner state machine:

function HierarchalStateMachine (description, prototype = Object.prototype) {

// ...

for (const state of Object.keys(MACHINES_TO_TRANSITIONS.get(machine))) {

const stateObject = Object.create(prototype);

// ...

const innerStateMachineDescription = stateDescription[INNER];

// ...

if (innerStateMachineDescription == null) {

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.get(machine)[state] = stateObject;

} else {

const innerStateMachine = HierarchalStateMachine(

innerStateMachineDescription,

stateObject

);

MACHINES_TO_NAMES_TO_STATES.get(machine)[state] = innerStateMachine;

}

}

// ...

}

One final thing. When we set the state for a state machine, we have to figure out whether the state machine can handle it, or whether it should delegate that to a nested state machine:

function setState (machine, stateName) {

const currentState = getState(machine);

if (hasState(machine, stateName)) {

setDirectState(machine, stateName)

} else if (isStateMachine(currentState)) {

setState(currentState, stateName);

} else {

console.log(`illegal transition to ${stateName}`, machine);

}

}

function setDirectState (machine, stateName) {

MACHINES_TO_CURRENT_STATE_NAMES.set(machine, stateName);

const newState = getState(machine);

Object.setPrototypeOf(machine, newState);

if (isStateMachine(newState)) {

setState(newState, MACHINES_TO_STARTING_STATES.get(newState));

}

}

Ta da!

(code)

There is, of course, much more work to be done. What should getCurrentState actually return? How will it show that an account might be in both open and not-held states? What about drawing DOT diagrams? How should our getTransitions and dot functions work to produce a nested state transitions diagram?

But before we do that work, perhaps we should look at the work that already exists:

statecharts

In the 1980s, David Harel invented the statechart notation for specifying and programming reactive systems. In addition to formalizing hierarchal state machines, statechart notation covers many other important topics like concurrency and parallel execution.

Harel’s original paper explains the entire idea.

Statecharts have a formal SCXML notation, and a number of actively maintained libraries implementing executable statecharts, including xstate, which bills itself as “functional, stateless JavaScript finite state machines and statecharts.” You may also want to take a look at the delightfully readable (but unfinished) statecharts.github.io project. There’s plenty to review in Wikipedia’s article on UML State Machines as well.

There’s a lot to digest!

But we’ve gotten the general idea, and that is enough for now. Now that we’ve done the work, let’s turn to the most pressing question: What is it good for? Why should we care?

rubber duck design

Hierarchal state machines seem like an awful lot of work for a model with a handful of methods, but let’s take a step back and think about the general principles involved. First, hierarchal state machines help us model the way people think about states more closely than if we had to translate what they are saying to a simple “flat” state machine.

Second, hierarchal state machines open up opportunities for composing state machines out of smaller parts. Being able to decompose and recompose models is a programming superpower.

Third, having a “meta-model”–whether it be hierarchal state machines or flat state machines–for constructing domain models provides an unexpected process benefit we might call “Rubber Duck Design.”

In software engineering, rubber duck debugging or rubber ducking is a method of debugging code. The name is a reference to a story in the book The Pragmatic Programmer in which a programmer would carry around a rubber duck and debug their code by forcing themselves to explain it, line-by-line, to the duck. Many other terms exist for this technique, often involving different inanimate objects.

Many programmers have had the experience of explaining a problem to someone else, possibly even to someone who knows nothing about programming, and then hitting upon the solution in the process of explaining the problem.

Rubber duck design works just like rubber duck debugging: The act of explaining the design prompts our brains to think through the thing we’re modelling more thoroughly than if we just stare at the code. What makes state machines–whether hierarchal or flat–particularly effective for this is that they force us to “explain to the computer” all of the states and transitions the entity we’re modelling will have.

As an incredibly fecund bonus, we also get dynamically generated diagrams and a cleaner form of self-documenting code in the form of the descriptions that makes it easier for others to read and modify our domain objects.

Whether we use the complete and rather heavyweight SCXML or build ourself a lightweight alternative, in many cases, modelling domain objects as state machines is a win.

(discuss on reddit)

javascript allongé, the six edition

If you enjoyed this essay, you’ll ❤️ JavaScript Allongé, the Six Edition. It’s 100% free to read online!

notes

-

Banking software is not actually written with objects that have methods like

.depositfor soooooo many reasons, but this toy example describes something most people understand on a basic level, even if they aren’t familiar with the needs of banking infrastructure, correctness, and so forth. ↩ -

We’re also using a slightly different pattern for associating state machines with their states, based on weak maps. ↩

-

mongle: v, to molest or disturb. ↩

-

Of course, we could implement a state machine in some other way, such that it behaves like a state machine but is implemented in some other fashion. That would be changing its implementation and not its interface. We could, for example, rewrite our

StateMachinefunction to generate a collection of actors communicating with asynchronous method passing. The value of our curent approach is that the implementation strongly mirrors the interface, which has certain benefits for readability. ↩ -

Or a bigger boat! ↩