Alice and Bobbie were comparing notes after interviewing interns for an upcoming work term with their company, HipCo. Their interview process, although often maligned on social media, worked reasonably well for their purposes: They spent an hour with each candidate, devoting twenty minutes to introductions and some basic behavioural questions, about half an hour to a basic programming problem, and the remaining ten minutes or so was turned over to the candidate to ask them questions.

They quickly went over all of the the candidates but one. Alice held that back for the end of their meeting.

“And then there was Sharleen,” said Alice. “Sharleen has decent marks, is in third year, and raised no red flags in the behavioural questions.” Bobbie waited, expecting a revelation with respect to the programming problem, and was not disappointed.

“I asked our usual question, determining whether a string of brackets was a valid Dyck Word, that is, a word in the Dyck language.”

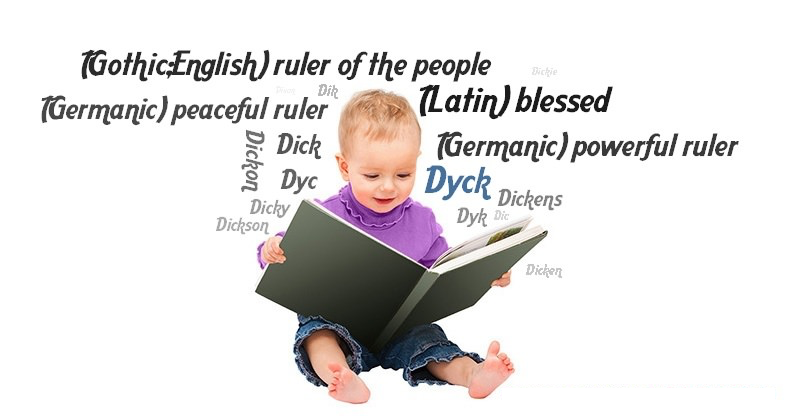

In the theory of formal languages of computer science, mathematics, and linguistics, a Dyck word is a balanced string of square brackets

[and]. The set of Dyck words forms the Dyck language.Dyck words and language are named after the mathematician Walther von Dyck. They have applications in the parsing of expressions that must have a correctly nested sequence of brackets, such as arithmetic or algebraic expressions.

[]is a Dyck Word, as are[][],[[]], and[[][]].][is not a Dyck Word, and neither are[]],[][][, or][][.Dyck words are easily explained to everyone with a basic grasp of arithmatic. If we take a valid arithmatic or algebraic expression that includes parenthesis, such as

a + (b + 2) - (c / (d - 1)), then remove everything except the parentheses, such as()(()), and finally turn them into square brackets,[][[]], what remains is a valid Dyck word if the orginal expression was properly parenthesized.

“Sharleen did write working code to determine whether a string was a valid Dyck Word. But it was unlike any solution I’ve ever seen before. She obviously didn’t memorize any of the solutions we find on those hack-the-job-interview web sites. Here’s what she presented to handle the simple case of only one type of parenthesis…”

determining whether a string is a valid dyck word

Here is Sharleen’s first solution:

function isDyckWord (before) {

if (before === '') return true;

const after = before.replace('[]','');

return (before !== after) && isDyckWord(after);

}

Having shared the solution with Bobbie, Alice continued.

“I was, I admit, surprised. Normally the first cut has some kind of stack, and then we ask abut optimizing to an integer. I asked about performance, and she cheerfully admitted that the solution was nearly maximally pessimum, with n-squared run time as the algorithm scans the string on every call to isDyckWord. But she pointed out that the solution is insanely simple, and she favours simplicity first, optimization second.”

“She was ridiculously complacent about this, so I poked at another problem. What, I asked her, would this do on when presented with a worst-case string, say one that consisted of 100,000 [s followed by 100,000 ]s? Was she not concerned with the possibility of a stack overflow?”

“Sharleen thought for a moment, then said that it depended very much upon the level of optimization in the JavaScript engine. A sufficiently smart just-in-time compiler would recognize that the call to isDyckWord(after) was effectively in tail position, and then use Tail Call Optimization to convert this recursive function into a loop.”

“But if it didn’t, Sharleen presented a trivial change:”

function isDyckWord (before) {

if (before === '') return true;

const after = before.replace('[]','');

if (before === after) {

return false;

} else {

return isDyckWord(after);

}

}

“JavaScript’s specification calls for Tail-Call Optimization, she explained, and thus this recursive function would be executed as a loop and not take up stack space proportional to the depth of the deepest nesting. I wondered aloud about space, and she was ready for my question: She explained that because this duplicated the string at each pass, it consumed space proportional to the size of the input, regardless of the depth of nesting.”

“I pulled out the question of an Extended Dyck Language that consists of multiple types of parentheses. Using the conventional solution of tracking the last seen opening parenthesis on a stack, we can convert the stack to a count when there is only one kind of parenthesis. But if we introduce additional types, e.g. [](){}, the stack must be used, and the solution requires space proportional to the deepest nesting.”

“I asked if she could create a solution for multiple parentheses, and if so, what space would it require? With a few keystrokes, Sharleen added the two new types of parentheses:”

function isExtendedDyckLanguageWord (before) {

if (before === '') return true;

const after = before.replace('[]','').replace('()','').replace('{}','');

if (before === after) {

return false;

} else {

return isExtendedDyckLanguageWord(after);

}

}

“I could see at once that this solution was likewise in tail call form and would require space proportional to the size of the input, as before.”

Bobbie was amazed at this idiosyncratic solution. “Well,” Bobbie said at last, “at least you weren’t discussing deterministic vs. non-deterministic pattern matching and its relationship to pushdown automata.”

“No,” Alice admitted, “the opposite. This solution was remarkably simple, even if it is the least performant thing I’ve ever seen. Sharleen had an outrageous amount of confidence to present this in an interview and cheerfully admit to its shortcomings.”

“So?” Asked Bobbie, “Did you press her to write a faster solution?”

“No,” Alice replied, “By this time I was sure that she was trolling me, and I’ll be damned if I was going to let her whip out a fast solution. So instead, I asked her what about JavaScript implementations–like V8 at this time–that don’t support TCO? In that case, she would still have a stack overflow.”

Bobbie pointed out that Alice had clearly gone beyond what was necessary to determine if Sharleen would be an effective intern. “I know,” said Alice, “But I was now all-in on wrangling this solution with Sharleen. I had well and truly fallen for the troll bait.” Bobbie admitted that she was likewise curious about whether Sharleen had an answer for this problem.

“Well,” Alice said, “Sharleen remembered that the code could be converted to use a trampoline, and asked if she could do a web search for the general approach. I assented, and thank god, she fell into a rabbit hole: She wound up reading some weird article about recursive combinators, and ran out of time before she could finish.”

Bobbie made a wry face. “Interviews are not supposed to be battles for intellectual superiority.” Alice’s face fell. “True, true. I got caught up in the moment. But come on, Sharleen was surely having a little joke at our expense.”

“Yes,” agreed Bobbie, “I expect she was. And why not? Interviewers pull a lot of stupid stunts, if once in a while a candidate trolls us with a joke solution, it’s 100% understandable. So any ways, did you do the standard thing and explain that she was free to finish the refactoring on her own time and email it to you?”

“I sure did,” said Alice, “And about twenty minutes later she had texted me a gist.”

sharleen’s trampolining solution

And here’s Sharleen’s solution, building upon a widowbird, a recursive combinator that implements trampolining:

const widowbird =

fn => {

class Thunk {

constructor (args) {

this.args = args;

}

evaluate () {

return fn(...this.args);

}

}

return (...initialArgs) => {

let value = fn(

(...args) => new Thunk(args),

...initialArgs

);

while (value instanceof Thunk) {

value = value.evaluate();

}

return value;

};

};

const isExtendedDyckLanguageWord =

widowbird(

(myself, before) => {

if (before === '') return true;

const after = before.replace('[]','').replace('()','').replace('{}','');

if (before === after) {

return false;

} else {

return myself(myself, after);

}

}

);

Alice and Bobbie started at the solution in all its glory. “Well,” said Bobbie, “This is amazingly clever, and amusingly so when you consider how bad its performance is!”

“Yes,” agreed Alice. “There is no question that Sharleen has the horsepower to write code. And she understands the tradeoffs. But do we have any concern that she’ll be too clever?”

Bobbie shook her head. “Interviews are necessarily artificial scenarios. It’s dangerous to jump to conclusions about somebody’s behaviour on-the-job based on a few lines of code written in an interview. That’s what we have the behavioural questions for. You said she was fine with the behavioural questions?”

Alice nodded.

“Well then,” said Bobbie, “The question is not whether we’ll make her an offer, it’s whether you were sufficiently interesting that she will accept.”

(discuss on reddit)