In this essay, we will take a look at some higher-order functions, with an eye to seeing how they can be used to make our programs more expressive, while balancing that against the need to limit the perceived complexity of our programs.

introduction: expressiveness

One of the most basic ideas in programming is that functions can invoke other functions.1

When a function invokes other functions, and when one function can be invoked by more than one other function, we have a very good thing. When we have a many-to-many relationship between functions, we have a more expressive power than when we have a one-to-many relationship. We have the ability to give each function a single responsibility, and name that responsibility. We also have the ability to ensure that one and only one function has that responsibility.

A many-to-many relationship between functions is what enables us to create a one-to-one relationship between functions and responsibilities.

Programmers often speak of languages as being expressive. Although there is no single universal definition for this word, most programmers agree that an important aspect of “expressiveness” is that the language makes it easy to write programs that are not unnecessarily verbose. If functions have many responsibilities, they become large and unwieldy. If the same responsibility needs to be implemented more than once, there is de facto redundancy.

Programs where functions have single responsibilities, and where responsibilities are implemented by single functions, avoid unnecessary verbosity.

Thus, facilitating the many-to-many relationship between functions makes it possible to write programs that are more expressive than those that do not have a many-to-many relationship between functions.

the dark side: perceived complexity

However, “With great power comes great responsibility.”2 The downside of a many-to-many relationship between functions is that the ‘space of things a program might do’ grows very rapidly as the size increases. “Expressiveness” is often in tension with “Perceived Complexity.”

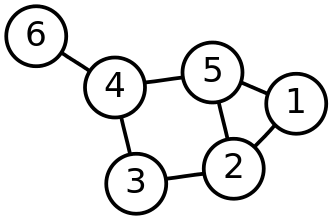

One way to think about this by analogy is to imagine we are drawing a graph. Each function is a vertex, and the calling relationship between them is an edge. Assuming that there is no “dead code,” every structured program forms a connected graph.

Given a known number of nodes, the number of different ways to draw a connected graph between them is the A001187 integer sequence. Its first eleven terms are: 1, 1, 1, 4, 38, 728, 26704, 1866256, 251548592, 66296291072, 34496488594816. Meaning that there are more than thirty-four trillion ways to organize a program with just ten functions.

This explosion of flexibility is so great that programmers have to temper it. The benefits of creating one-to-one relationships between functions and responsibilities can become overwhelmed by the difficulty of understanding programs with unconstrained potential complexity.

JavaScript has tools to help. Its blocks create namespaces, and so do its formal modules. It may soon have private object properties.

Namespaces constrain large graphs into many smaller graphs, each of which has a constrained set of ways they can be connected to other graphs. It’s still a large graph, but the number of possible ways to draw it is smaller, and by analogy, it is easier to sort out what it does, and how.

What we have described is a heuristic for designing good software systems: Provide the flexibility to use many-to-many relationships between entities, while simultaneously providing ways for programmers to intentionally limit the ways that entities can be connected.

But notice that we’re not saying that one mechanism does both jobs. No, we’re saying that one tool helps us increase expressivity, while another helps us limit the perceived complexity of our programs, and the two work in tension with each other.

Now that we’ve established our heuristic, let’s look at some higher-order functions, and see what they can tell us about expressiveness and perceived complexity.

Brown Mandelbrot, © 2008 docnic, Some rights reserved

higher-order functions

Functions that accept functions as parameters, and/or return functions as values, are called Higher-Order Functions, or “HOFs.” Languages that support HOFs also support the idea of functions as first-class values, and nearly always support the idea of dynamically creating functions.

HOFs give programmers even more ways to decompose and compose programs, and thus more ways to write programs where there is a one-to-one relationship between functions and responsibilities. Let’s look at an example.

Rumour has it that there are excellent companies that ask coöp students to write code as part of the interview process. A typical problem will ask the student to demonstrate their facility solving a problem that ought to be familiar to a computer science or computer engineering student.

For example, merging two sorted lists. This is something a student will have at least looked at, and it does have some applicability to modern service architectures. Here’s a naïve implementation:

function merge ({ list1, list2 }) {

if (list1.length === 0 || list2.length === 0) {

return list1.concat(list2);

} else {

let atom, remainder;

if (list1[0] < list2[0]) {

atom = list1[0];

remainder = {

list1: list1.slice(1),

list2

};

} else {

atom = list2[0],

remainder = {

list1,

list2: list2.slice(1)

};

}

const left = atom;

const right = merge(remainder);

return [left, ...right];

}

}

merge({

list1: [1, 2, 5, 8],

list2: [3, 4, 6, 7]

})

//=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]

And here’s a function that finds the sum of a list of numbers:

function sum(list) {

if (list.length === 0) {

return 0;

} else {

const [atom, ...remainder] = list;

const left = atom;

const right = sum(remainder);

return left + right;

}

}

sum([42, 3, -1])

//=> 44

We’ve written them so that both have the same structure, they are linearly recursive. Can we extract this structure?

linrec

Linear recursion has a simple form:

- Look at the input. Can we break an element off?

- If not, what value do we return?

- If we can break a chunk off, divide the input into the element and a remainder

- Run our linearly recursive function on the remainder, then

- Combine our chunk with the result of our linearly recursive function on the remainder

Both of our examples above have this form, and we will write a higher-order function to implement linear recursion. To get started with our extraction, it helps to take an example of the function we want to implement, and extract its future parameters as constants:

function sum(list) {

const indivisible = (list) => list.length === 0;

const value = () => 0;

const divide = (list) => {

const [atom, ...remainder] = list;

return { atom, remainder }

};

const combine = ({ left, right }) => left + right;

if (indivisible(list)) {

return value(list);

} else {

const { atom, remainder } = divide(list);

const left = atom;

const right = sum(remainder);

return combine({ left, right });

}

}

We’re just about ready to make our higher-order function. Our penultimate step is to rename sum to myself, and list to input:

function myself (input) {

const indivisible = (list) => list.length === 0;

const value = () => 0;

const divide = (list) => {

const [atom, ...remainder] = list;

return { atom, remainder }

};

const combine = ({ left, right }) => left + right;

if (indivisible(input)) {

return value(input);

} else {

const { atom, remainder } = divide(input);

const left = atom;

const right = myself(remainder);

return combine({ left, right });

}

}

The final step is to turn our constant functions into parameters of a function that returns our myself function:

function linrec({ indivisible, value, divide, combine }) {

return function myself (input) {

if (indivisible(input)) {

return value(input);

} else {

const { atom, remainder } = divide(input);

const left = atom;

const right = myself(remainder);

return combine({ left, right });

}

}

}

const sum = linrec({

indivisible: (list) => list.length === 0,

value: () => 0,

divide: (list) => {

const [atom, ...remainder] = list;

return { atom, remainder }

},

combine: ({ left, right }) => left + right

});

And now we can exploit the similarities between sum and merge, by using linrec to write merge as well:

const merge = linrec({

indivisible: ({ list1, list2 }) => list1.length === 0 || list2.length === 0,

value: ({ list1, list2 }) => list1.concat(list2),

divide: ({ list1, list2 }) => {

if (list1[0] < list2[0]) {

return {

atom: list1[0],

remainder: {

list1: list1.slice(1),

list2

}

};

} else {

return {

atom: list2[0],

remainder: {

list1,

list2: list2.slice(1)

}

};

}

},

combine: ({ left, right }) => [left, ...right]

});

But why stop there?

binrec

binrec is a higher-order function for implementing binary recursion. Remember our coöp student implementing a merge between sorted lists? One of the cool things you can do with a merge function is write a merge sort, and advanced students are often asked to at least sketch out how it would work.

binrec is actually simpler than linrec in at least one respect, because instead of having an element and a remainder, binrec divides a problem into two parts and applies the same algorithm to both halves:

function binrec({ indivisible, value, divide, combine }) {

return function myself (input) {

if (indivisible(input)) {

return value(input);

} else {

let { left, right } = divide(input);

left = myself(left);

right = myself(right);

return combine({ left, right });

}

}

}

const mergeSort = binrec({

indivisible: (list) => list.length <= 1,

value: (list) => list,

divide: (list) => ({

left: list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

right: list.slice(list.length / 2)

}),

combine: ({ left: list1, right: list2 }) => merge({ list1, list2 })

});

mergeSort([1, 42, 4, 5])

//=> [1, 4, 5, 42]

From binrec, we can derive multirec, which divides the problem into an arbitrary number of symmetrical parts:

function mapWith (fn) {

return function * (iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

yield fn(element);

}

};

}

function multirec({ indivisible, value, divide, combine }) {

return function myself (input) {

if (indivisible(input)) {

return value(input);

} else {

const parts = divide(input);

const solutions = mapWith(myself)(parts);

return combine(solutions);

}

}

}

const mergeSort = multirec({

indivisible: (list) => list.length <= 1,

value: (list) => list,

divide: (list) => [

list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

list.slice(list.length / 2)

],

combine: ([list1, list2]) => merge({ list1, list2 })

});

There are an infinitude of higher-order functions we could explore, but these are enough for now. Let’s return to thinking about the relationship between expressiveness and perceived complexity.

the relationship between higher-order functions, expressiveness, and complexity

In typical programming, functions invoke each other, and by creating many-to-many relationships between functions, we increase expressiveness by making sure that one and only one functions implements any one responsibility. If two functions implement the same responsibility, we are less DRY, and less expressive.

How do higher-order functions come into this? Well, as we saw, merge and sum have different responsibilities in the solution domain–merging lists and summing lists. But they share a common implementation structure, linear recursion. Therefore, they both are responsible for implementing a linearly recursive algorithm.

By extracting this algorithm into linrec, we once again make sure that one and only one entity–linrec is responsible for implementing linear recursion. Thus, we find that a feature like first-class functions does give us the power of greater expressiveness, as it gives us at least one more way to create many-to-many relationships between functions.

And we also know that this can increase perceived complexity if we do not also temper this increased expressiveness with language features or architectural designs that allow us to define groups of functions that have rich relationships within themselves, but only limited relationships with other groups.

Photo © 2010 Denis Mihailov, some rights reserved

one-to-many and many-to-many

There’s more to it than that. Let’s compare binrec and multirec. Or rather, let’s compare how we write mergeSort using binrec and multirec:

const mergeSort1 = binrec({

indivisible: (list) => list.length <= 1,

value: (list) => list,

divide: (list) => ({

left: list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

right: list.slice(list.length / 2)

}),

combine: ({ left: list1, right: list2 }) => merge({ list1, list2 })

});

const mergeSort2 = multirec({

indivisible: (list) => list.length <= 1,

value: (list) => list,

divide: (list) => [

list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

list.slice(list.length / 2)

],

combine: ([list1, list2]) => merge({ list1, list2 })

});

The interesting thing for us are the functions we supply as arguments. Let’s name them:

const hasAtMostOne = (list) => list.length <= 1;

const Identity = (list) => list;

const bisectLeftAndRight = (list) => ({

left: list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

right: list.slice(list.length / 2)

});

const bisect = (list) => [

list.slice(0, list.length / 2),

list.slice(list.length / 2)

];

const mergeLeftAndRight = ({ left: list1, right: list2 }) => merge({ list1, list2 });

const mergeBisected = ([list1, list2]) => merge({ list1, list2 });

Looking at the names and at what the functions do, it seems that some, namely hasAtMostOne, Identity, and bisect feel like general-purpose functions that we might find ourselves using throughout one or many programs. And in fact, they can often be found in general-purpose function utility libraries. They express universal operations on lists.

Whereas, bisectLeftAndRight, and mergeLeftAndRight, seem more specialized. They are unlikely to be used anywhere else. mergeBisected is a toss-up. We might need it elsewhere, we might not.

We can also say that there is a many-to-many relationship between functions in our programs and the hasAtMostOne, Identity, and bisect functions. Functions like mergeSort2 call many other functions, and functions like bisect can be called by many other functions.

And as noted in the beginning, this “many-to-many-ness” contributes to expressiveness and to ensuring that we can write software where there is a one-to-one relationship between entities and responsibilities. For example, bisect is the authority on bisecting lists. We can arrange to write all of our code to invoke bisect, rather than duplicating its functionality.

Our heuristic is that the more general-purpose the interface and behavioural “contract” that a function provides, and the more focused and simple a responsibility it has, the greater its “many-to-many-ness.” Therefore, when we write higher-order functions like multirec, we should strive to design them to accept general-purpose parameters with simple responsibilities.

But we can also write functions like bisectLeftAndRight and mergeLeftAndRight. But when we do, there will be a one-to-many relationship, because we have little use for them outside of our specific merge application. This does allow us to structure our code and extract commonality like how to perform a binary recursion, but by limiting the many-to-many-ness of our program, we limit its expressiveness.

Unfortunately, this limitation of expressiveness does not directly translate to limiting the perceived complexity of our programs. We can tell from detailed inspection that a function like bisectLeftAndRight will not be useful elsewhere in the program, but if we do not employ a tool like module scoping to enforce this and make it obvious at a glance, we do not really limit its perceived complexity.

From this we can observe that many programming techniques, such as writing highly specialized interfaces for functions, or having complex responsibilities, can serve to limit a program’s expressiveness without providing the benefit of limiting its perceived complexity.

Framework, © 2006 kaz k, some rights reserved

what higher-order functions tell us about frameworks and libraries

Roughly speaking, both frameworks and libraries are collections of classes, functions, and other code that we blend with our own code to write programs. But frameworks are designed to call our code, while libraries are designed to be called by our code.

Frameworks typically expect us to write functions or create entities with very specific, proprietary interfaces and behavioural contracts. For example, Ember requires us to extend its own base classes for things like component classes, instead of using ordinary JavaScript ES-6 classes. As we noted above, when we have specific interfaces, we limit the expressiveness of our programs, but not the incidental complexity.

The underlying assumption is that we are writing code for the framework, so the framework’s author is not concerned with setting-up a many-to-many relationship between the framework’s code and our code. For example, we cannot use JavaScript mixins, subclass factories, or method advice with the classes we write in Ember. We have to use the specific, proprietary meta-programming facilities that Ember provides, or are provided in specific plugins written for Ember.

Framework-oriented code tends to be more one-to-many than many-to-many, and thus tends to be less expressive.

Whereas, libraries are designed to be called by our code. And more importantly, by the code of many, many different teams, each of whom have their own programming style and approach. This leads library authors in general to write functions with generic interfaces and simple responsibilities.

Library-oriented code tends to be more many-to-many than one-to-many, and thus can be more expressive.

Is framework-oriented code a bad thing? It’s a tradeoff. Frameworks provide standard ways to do things. Frameworks hold out the promise of doing more things for us, and especially doing more complex things for us.

Ideally, although our code may be less expressive with a framework, our goal should be that we write less code against a framework than we would using libraries, and that we use other mechanisms to limit the perceived complexity of our code.

But from our exploration of linrec, binrec, and multirec, we can see that higher-order functions teach us something about specific and general interfaces, and that teaches us something about the tradeoffs between using frameworks and libraries.

afterward

There is more to read about multirec in the follow-up essay, Why recursive data structures?, and the final chapter, Time, Space, and Life As We Know It.

An early draft of this post was reviewed by Jinny Kim and Peter Sobot. Thank you.

Have an observation? Spot an error? You can open an issue, discuss this on reddit, or even edit this post yourself.

And hey: If you like this essay, you’ll love JavaScript Allongé. It’s free to read online!

notes

-

Although this essay is going to talk about functions, everything we look at is applicable to methods and by analogy, to classes. We’re just sticking to talking about functions for simplicity’s sake. ↩

-

“Ils doivent envisager qu’une grande responsabilité est la suite inséparable d’un grand pouvoir.”—quoteinvestigator.com ↩