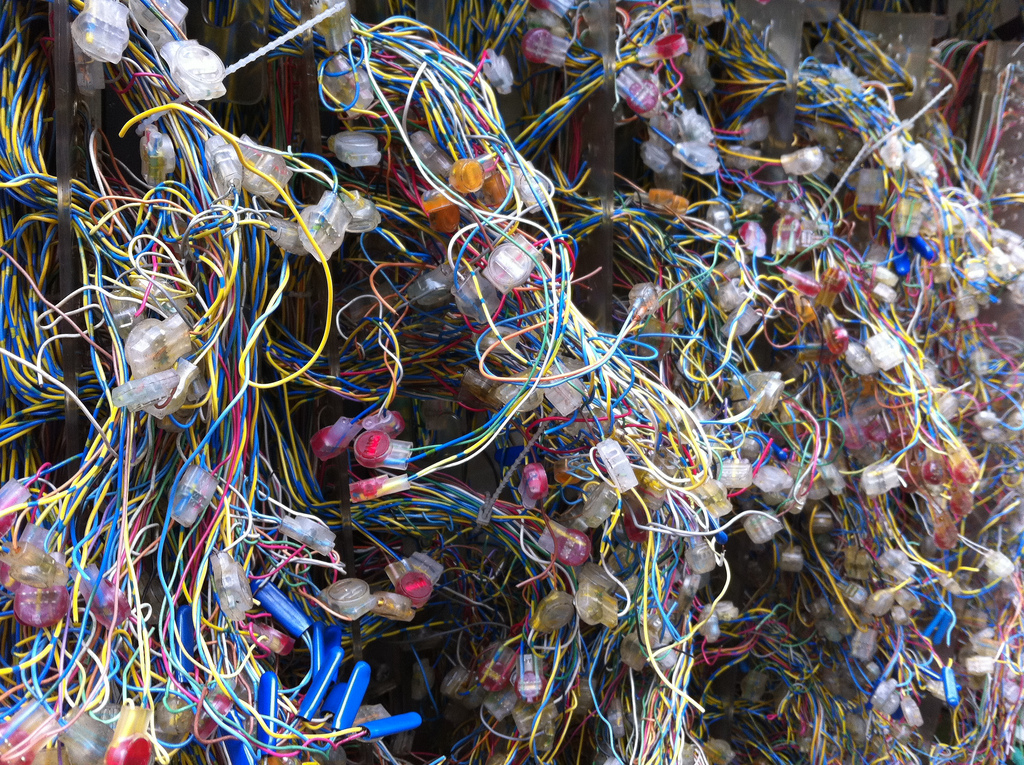

Mixins solve a very common problem in class-centric OOP: For non-trivial applications, there is a messy many-to-many relationship between behaviour and classes, and it does not neatly decompose into a tree. In this essay, we only touch lightly over the benefits of using mixins with classes, and in their stead we will focus on some of the limitations of mixins and ways to not just overcome them, but create designs that are superior to those created with classes alone.

(For more on why mixins matter in the first place, you may want to review Prototypes are Objects (and why that matters), Functional Mixins in ECMAScript 2015, and Using ES.later Decorators as Mixins.)

simple mixins

As noted above, for non-trivial applications, there is a messy many-to-many relationship between behaviour and classes. However, JavaScript’s single-inheritance model forces us to organize behaviour in trees, which can only represent one-to-many relationships.

The mixin solution to this problem is to leave classes in a single inheritance hierarchy, and to mix additional behaviour into individual classes as needed. Here’s a vastly simplified functional mixin for classes:1

function mixin (behaviour) {

let instanceKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(behaviour);

let typeTag = Symbol('isa');

function _mixin (clazz) {

for (let property of instanceKeys)

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, property, {

value: behaviour[property],

writable: true

});

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, typeTag, { value: true });

return clazz;

}

Object.defineProperty(_mixin, Symbol.hasInstance, {

value: (i) => !!i[typeTag]

});

return _mixin;

}

This is more than enough to do a lot of very good work in JavaScript, but it’s just the starting point. Here’s how we put it to work:

let BookCollector = mixin({

addToCollection (name) {

this.collection().push(name);

return this;

},

collection () {

return this._collected_books || (this._collected_books = []);

}

});

class Person {

constructor (first, last) {

this.rename(first, last);

}

fullName () {

return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;

}

rename (first, last) {

this.firstName = first;

this.lastName = last;

return this;

}

}

let Executive = BookCollector(

class extends Person {

constructor (title, first, last) {

super(first, last);

this.title = title;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.title} ${super.fullName()}`;

}

}

);

let president = new Executive('President', 'Barak', 'Obama');

president

.addToCollection("JavaScript Allongé")

.addToCollection("Kestrels, Quirky Birds, and Hopeless Egocentricity");

president.collection()

//=> ["JavaScript Allongé","Kestrels, Quirky Birds, and Hopeless Egocentricity"]

multiple inheritance

If you want to mix behaviour into a class, mixins do the job very nicely. But sometimes, people want more. They want multiple inheritance. Meaning, what they really want is for class Executive to inherit from Person and from BookCollector.

What’s the difference between Executive mixing BookCollector in and Executive inheriting from BookCollector?

- If

ExecutivemixesBookCollectorin, the propertiesaddToCollectionandcollectionbecome own properties ofExecutive’s prototype. IfExecutiveinherits fromBookCollector, they don’t. - If

ExecutivemixesBookCollectorin,Executivecan’t override methods ofBookCollector. IfExecutiveinherits fromBookCollector, it can. - If

ExecutivemixesBookCollectorin,Executivecan’t override methods ofBookCollector, and therefore it can’t make a method that overrides a method ofBookCollectorand then usessuperto call the original. IfExecutiveinherits fromBookCollector, it can.

If JavaScript had multiple inheritance, we could extend a class with more than one superclass:

class Todo {

constructor (name) {

this.name = name || 'Untitled';

this.done = false;

}

do () {

this.done = true;

return this;

}

undo () {

this.done = false;

return this;

}

toHTML () {

return this.name; // highly insecure

}

}

class Coloured {

setColourRGB ({r, g, b}) {

this.colourCode = {r, g, b};

return this;

}

getColourRGB () {

return this.colourCode;

}

}

let yellow = {r: 'FF', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

red = {r: 'FF', g: '00', b: '00'},

green = {r: '00', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

grey = {r: '80', g: '80', b: '80'};

let oneDayInMilliseconds = 1000 * 60 * 60 * 24;

class TimeSensitiveTodo extends Todo, Coloured {

constructor (name, deadline) {

super(name);

this.deadline = deadline;

}

getColourRGB () {

let slack = this.deadline - Date.now();

if (this.done) {

return grey;

}

else if (slack <= 0) {

return red;

}

else if (slack <= oneDayInMilliseconds){

return yellow;

}

else return green;

}

toHTML () {

let rgb = this.getColourRGB();

return `<span style="color: #${rgb.r}${rgb.g}${rgb.b};">${super.toHTML()}</span>`;

}

}

This hypothetical TimeSensitiveTodo extends both Todo and Coloured, and it overrides toHTML from Todo as well as overriding getColourRGB from Coloured.

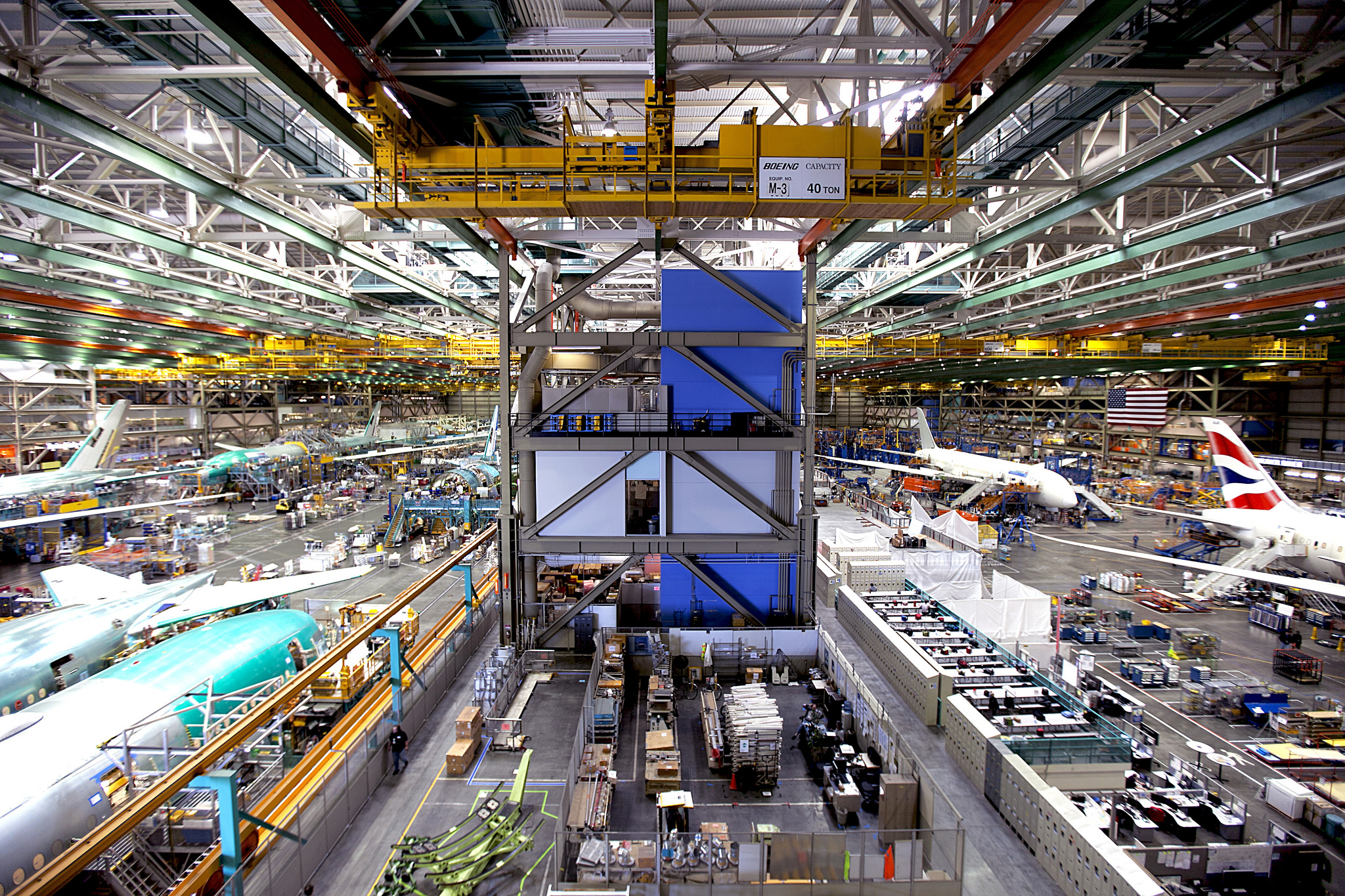

subclass factories

However, JavaScript does not have “true” multiple inheritance, and therefore this code does not work. But we can simulate multiple inheritance for cases like this. The way it works is to step back and ask ourselves, “What would we do if we didn’t have mixins or multiple inheritance?”

The answer is, we’d force a square multiple inheritance peg into a round single inheritance hole, like this:

class Todo {

// ...

}

class ColouredTodo extends Todo {

// ...

}

class TimeSensitiveTodo extends ColouredTodo {

// ...

}

By making ColouredTodo extend Todo, TimeSensitiveTodo can extend ColouredTodo and override methods from both. This is exactly what most programmers do, and we know that it is an anti-pattern, as it leads to duplicated class behaviour and deep class hierarchies.

But.

What if, instead of manually creating this hierarchy, we use our simple mixins to do the work for us? We can take advantage of the fact that classes are expressions, like this:

let Coloured = mixin({

setColourRGB ({r, g, b}) {

this.colourCode = {r, g, b};

return this;

},

getColourRGB () {

return this.colourCode;

}

});

let ColouredTodo = Coloured(class extends Todo {});

Thus, we have a ColouredTodo that we can extend and override, but we also have our Coloured behaviour in a mixin we can use anywhere we like without duplicating its functionality in our code. The full solution looks like this:

class Todo {

constructor (name) {

this.name = name || 'Untitled';

this.done = false;

}

do () {

this.done = true;

return this;

}

undo () {

this.done = false;

return this;

}

toHTML () {

return this.name; // highly insecure

}

}

let Coloured = mixin({

setColourRGB ({r, g, b}) {

this.colourCode = {r, g, b};

return this;

},

getColourRGB () {

return this.colourCode;

}

});

let ColouredTodo = Coloured(class extends Todo {});

let yellow = {r: 'FF', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

red = {r: 'FF', g: '00', b: '00'},

green = {r: '00', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

grey = {r: '80', g: '80', b: '80'};

let oneDayInMilliseconds = 1000 * 60 * 60 * 24;

class TimeSensitiveTodo extends ColouredTodo {

constructor (name, deadline) {

super(name);

this.deadline = deadline;

}

getColourRGB () {

let slack = this.deadline - Date.now();

if (this.done) {

return grey;

}

else if (slack <= 0) {

return red;

}

else if (slack <= oneDayInMilliseconds){

return yellow;

}

else return green;

}

toHTML () {

let rgb = this.getColourRGB();

return `<span style="color: #${rgb.r}${rgb.g}${rgb.b};">${super.toHTML()}</span>`;

}

}

let task = new TimeSensitiveTodo('Finish blog post', Date.now() + oneDayInMilliseconds);

task.toHTML()

//=> <span style="color: #FFFF00;">Finish blog post</span>

The key snippet is let ColouredTodo = Coloured(class extends Todo {});, it turns behaviour into a subclass that can be extended and overridden. We can turn this pattern into a function:

let subclassFactory = (behaviour) => {

let mixBehaviourInto = mixin(behaviour);

return (superclazz) => mixBehaviourInto(class extends superclazz {});

}

Using subclassFactory, we wrap the class we want to extend, instead of the class we are declaring. Like this:

let subclassFactory = (behaviour) => {

let mixBehaviourInto = mixin(behaviour);

return (superclazz) => mixBehaviourInto(class extends superclazz {});

}

let ColouredAsWellAs = subclassFactory({

setColourRGB ({r, g, b}) {

this.colourCode = {r, g, b};

return this;

},

getColourRGB () {

return this.colourCode;

}

});

class TimeSensitiveTodo extends ColouredAsWellAs(ToDo) {

constructor (name, deadline) {

super(name);

this.deadline = deadline;

}

getColourRGB () {

let slack = this.deadline - Date.now();

if (this.done) {

return grey;

}

else if (slack <= 0) {

return red;

}

else if (slack <= oneDayInMilliseconds){

return yellow;

}

else return green;

}

toHTML () {

let rgb = this.getColourRGB();

return `<span style="color: #${rgb.r}${rgb.g}${rgb.b};">${super.toHTML()}</span>`;

}

}

The syntax of class TimeSensitiveTodo extends ColouredAsWellAs(ToDo) says exactly what we mean: We are extending our Coloured behaviour as well as extending ToDo.2

another way forward

The solution subclass factories offer is emulating inheritance from more than one superclass. That, in turn, makes it possible to override methods from our superclass as well as the behaviour we want to mix in. Which is fine, but we don’t actually want multiple inheritance!

It’s just that we’re looking at an overriding/extending methods problem, but we’re holding an inheritance-shaped hammer. So it looks like a multiple-inheritance nail. But what if we address the problem of overriding and extending methods directly, rather than indirectly via multiple inheritance?

simple overwriting with simple mixins

We start by noting that in the first pass of our mixin function, we blindly copied properties from the mixin into the class’s prototype, whether the class defined those properties or not. So if we write:

let RED = { r: 'FF', g: '00', b: '00' },

WHITE = { r: 'FF', g: 'FF', b: 'FF' },

ROYAL_BLUE = { r: '41', g: '69', b: 'E1' },

LIGHT_BLUE = { r: 'AD', g: 'D8', b: 'E6' };

let BritishRoundel = mixin({

shape () {

return 'round';

},

roundels () {

return [RED, WHITE, ROYAL_BLUE];

}

})

let CanadianAirForceRoundel = BritishRoundel(class {

roundels () {

return [RED, WHITE, LIGHT_BLUE];

}

});

new CanadianAirForceRoundel().roundels()

//=> [

{"r":"FF","g":"00","b":"00"},

{"r":"FF","g":"FF","b":"FF"},

{"r":"41","g":"69","b":"E1"}

]

Our CanadianAirForceRoundel’s third stripe winds up being regular blue instead of light blue, because the roundels method from the mixin BritishRoundel overwrites its own. (Yes, this is a ridiculous example, but it gets the point across.)

We can fix this by not overwriting a property if the class already defines it. That’s not so hard:

function mixin (behaviour) {

let instanceKeys = Reflect.ownKeys(behaviour);

let typeTag = Symbol('isa');

function _mixin (clazz) {

for (let property of instanceKeys)

if (!clazz.prototype.hasOwnProperty(property)) {

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, property, {

value: behaviour[property],

writable: true

});

}

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, typeTag, { value: true });

return clazz;

}

Object.defineProperty(_mixin, Symbol.hasInstance, {

value: (i) => !!i[typeTag]

});

return _mixin;

}

Now we can override roundels in CanadianAirForceRoundel while mixing shape in just fine:

new CanadianAirForceRoundel().roundels()

//=> [

{"r":"FF","g":"00","b":"00"},

{"r":"FF","g":"FF","b":"FF"},

{"r":"AD","g":"D8","b":"E6"}

]

The method defined in the class is now the “definition of record,” just as we might expect. But it’s not enough in and of itself.

combining advice with simple mixins

The above adjustment to ‘mixin’ is fine for simple overwriting, but what about when we wish to modify or extend a method’s behaviour while still invoking the original? Recall that our TimeSensitiveTodo example performed a simple override of getColourRGB, but its implementation of toHTML used super to invoke the method it was overriding.

Our adjustment will not allow a method in the class to invoke the body of a method in a mixin. So we can’t use it to implement TimeSensitiveTodo. For that, we need a different tool, method advice.

Method advice is a powerful tool in its own right: It allows us to compose method functionality in a declarative way. Here’s a simple “override” function that decorates a class:

let override = (behaviour, ...overriddenMethodNames) =>

(clazz) => {

if (typeof behaviour === 'string') {

behaviour = clazz.prototype[behaviour];

}

for (let overriddenMethodName of overriddenMethodNames) {

let overriddenMethodFunction = clazz.prototype[overriddenMethodName];

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, overriddenMethodName, {

value: function (...args) {

return behaviour.call(this, overriddenMethodFunction.bind(this), ...args);

},

writable: true

});

}

return clazz;

};

It takes behaviour in the form of a name of a method or a function, and one or more names of methods to override. It overrides each of the methods with the behaviour, which is invoked with the overridden method’s function as the first argument.

This allows us to invoke the original without needing to use super. And although we don’t show all the other use cases here, it is handy for far more than overriding mixin methods, it can be used to decompose methods into separate responsibilities.

Using override, we can decorate methods with any arbitrary functionality. We’d use it like this:

class Todo {

constructor (name) {

this.name = name || 'Untitled';

this.done = false;

}

do () {

this.done = true;

return this;

}

undo () {

this.done = false;

return this;

}

toHTML () {

return this.name; // highly insecure

}

}

let Coloured = mixin({

setColourRGB ({r, g, b}) {

this.colourCode = {r, g, b};

return this;

},

getColourRGB () {

return this.colourCode;

}

});

let yellow = {r: 'FF', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

red = {r: 'FF', g: '00', b: '00'},

green = {r: '00', g: 'FF', b: '00'},

grey = {r: '80', g: '80', b: '80'};

let oneDayInMilliseconds = 1000 * 60 * 60 * 24;

let TimeSensitiveTodo = override('wrapWithColour', 'toHTML')(

Coloured(

class extends Todo {

constructor (name, deadline) {

super(name);

this.deadline = deadline;

}

getColourRGB () {

let slack = this.deadline - Date.now();

if (this.done) {

return grey;

}

else if (slack <= 0) {

return red;

}

else if (slack <= oneDayInMilliseconds){

return yellow;

}

else return green;

}

wrapWithColour (original) {

let rgb = this.getColourRGB();

return `<span style="color: #${rgb.r}${rgb.g}${rgb.b};">${original()}</span>`;

}

}

)

);

let task = new TimeSensitiveTodo('Finish blog post', Date.now() + oneDayInMilliseconds);

task.toHTML()

//=> <span style="color: #FFFF00;">Finish blog post</span>

With this solution, we’ve used our revamped mixin function to support getColourRGB overriding the mixin’s definition, and we’ve used override to support wrapping functionality around the original toHTML method.

As a final bonus, if we are using a transpiler that supports ES.who-knows-when, we can use the proposed class decorator syntax:

@override('wrapWithColour', 'toHTML')

@Coloured

class TimeSensitiveTodo extends Todo {

constructor (name, deadline) {

super(name);

this.deadline = deadline;

}

getColourRGB () {

let slack = this.deadline - Date.now();

if (this.done) {

return grey;

}

else if (slack <= 0) {

return red;

}

else if (slack <= oneDayInMilliseconds){

return yellow;

}

else return green;

}

wrapWithColour (original) {

let rgb = this.getColourRGB();

return `<span style="color: #${rgb.r}${rgb.g}${rgb.b};">${original()}</span>`;

}

}

This is extremely readable.

method advice beyond extending mixin methods

override in and of itself is not spectacular. But most functionality that extends the behaviour of a method doesn’t process the result of the original. Most extensions do some work before the method is invoked, or do some work after the method is invoked.

So in addition to override, or toolbox should include before and after method advice. before invokes the behaviour first, and if its return value is undefined or truthy, it invokes the decorated method:

let before = (behaviour, ...decoratedMethodNames) =>

(clazz) => {

if (typeof behaviour === 'string') {

behaviour = clazz.prototype[behaviour];

}

for (let decoratedMethodName of decoratedMethodNames) {

let decoratedMethodFunction = clazz.prototype[decoratedMethodName];

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, decoratedMethodName, {

value: function (...args) {

let behaviourValue = behaviour.apply(this, ...args);

if (behaviourValue === undefined || !!behaviourValue)

return decoratedMethodFunction.apply(this, args);

},

writable: true

});

}

return clazz;

};

before should be used to decorate methods with setup or validation behaviour. Its “partner” is after, a decorator that runs behaviour after the decorated method is invoked:

let after = (behaviour, ...decoratedMethodNames) =>

(clazz) => {

if (typeof behaviour === 'string') {

behaviour = clazz.prototype[behaviour];

}

for (let decoratedMethodName of decoratedMethodNames) {

let decoratedMethodFunction = clazz.prototype[decoratedMethodName];

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, decoratedMethodName, {

value: function (...args) {

let decoratedMethodValue = ecoratedMethodFunction.apply(this, args);

behaviour.apply(this, ...args);

return decoratedMethodValue;

},

writable: true

});

}

return clazz;

};

With before, after, and override in hand, we have several advantages over traditional method overriding. First, before and after do a better job of declaring our intent when decomposing behaviour. And second, method advice allows us to add behaviour to multiple methods at once, focusing responsibility for cross-cutting concerns, like this:

const mustBeLoggedIn = () => {

if (currentUser() == null)

throw new PermissionsException("Must be logged in!");

}

const mustBeMe = () => {

if (currentUser() == null || !currentUser().person().equals(this))

throw new PermissionsException("Must be me!");

}

@HasAge

@before(mustBeMe, 'setName', 'setAge', 'age')

@before(mustBeLoggedIn, 'fullName')

class Person {

setName (first, last) {

this.firstName = first;

this.lastName = last;

}

fullName () {

return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;

}

};

Mixins allow us to have a many-to-many relationship between behaviour and classes. Method advice is similar: It makes a many-to-many relationship between behaviour and methods particularly easy to declare.

After using mixins and method advice on a regular basis, instead of using superclasses for shared behaviour, we use mixins and method advice instead. Superclasses are then relegated to those cases where we need to build behaviour into the constructor.

wrapping up

A simple mixin can cover many cases, but when we wish to override or extend method behaviour, we need to either use the subclass factory pattern or incorporate method advice. Method advice offers benefits above and beyond overriding mixin methods, especially if we use before and after in addition to override.

That being said, subclass factories are most convenient of we are comfortable with hierarchies of superclasses and with using super to extend method behaviour. Subclass factories work best when we don’t have a lot of behaviour that needs to be shared between different methods.

Method advice permits us to use a simpler approach to mixins, and makes it easy to have a many-to-many relationship between methods and behaviour, and it makes it easy to factor the responsibility for cross-cutting concerns out of each method.

No matter which approach we use, we find ourselves needing shallower and shallower class hierarchies when we use mixins to their fullest. Which demonstrates the power of working with simple constructs (like mixins and decorators) in JavaScript: We do not need nearly as much of the heavyweight OOP apparatus borrowed from 30 year-old languages, we just need to use the language we already have, in ways that cut with its grain.

(discuss on hacker news)

more reading:

- Prototypes are Objects (and why that matters)

- Classes are Expressions (and why that matters)

- Functional Mixins in ECMAScript 2015

- Using ES.later Decorators as Mixins

- Method Advice in Modern JavaScript

super()considered hmmm-ful- JavaScript Mixins, Subclass Factories, and Method Advice

- This is not an essay about ‘Traits in Javascript’

notes:

-

A production-ready implementation would handle more than just methods. For example, it would allow you to mix getters and setters into a class, and it would allow us to attach properties or methods to the target class itself, and not just instances. But this simplified version handles methods, simple properties, “mixin properties,” and

instanceof, and that is enough for the purposes of investigating OO design questions. ↩ -

Justin Fagnani named this pattern “subclass factory” in his essay “Real” Mixins with JavaScript Classes. It’s well worth a read, and his implementation touches on other matters such as optimizing performance on modern JavaScript engines. ↩