Interviewer: “Please whiteboard an algorithm that Counts the leaves in a tree/Solves Towers of Hanoi/Random pet recursion problem.”

Interviewee: “Ok… Scribble, scribble… That should do it.”

Interviewer: “That looks like it works, but can you convert it to an iterative solution?”

Interviewee: “Hmmmm…”

The good news is that every recursive algorithm can be implemented with iteration. Whether we should implement a recursive algorithm with iteration is, as they say, “an open problem,” and the factors going into that decision are so varied that there is no absolute “Always favour recursion” or “Never use recursion” answer.

However, what we can say with certainty is that knowing how to implement a recursive algorithm with iteration is deeply interesting! And as a bonus, this knowledge is useful when we do encounter one of the situations where we want to convert an algorithm that is normally recursive into an iterative algorithm.

Even if we never encounter this exact question in an interview.

recursion, see recursion

The shallow definition of a recursive algorithm is a function that directly or indirectly calls itself. Digging a little deeper, most recursive algorithms address the situation where the solution to a problem can be obtained by dividing it into smaller pieces that are similar to the initial problem, solving them, and then combining the solution.

This is known as “divide and conquer,” and here is an example: Counting the number of leaves in a tree. Our tree is represented as an object of type Tree that contains one ore more children. Each child is either a single leaf, represented as an object of class Leaf, or a subtree, represented as another object of type Tree.

So a tree that contains a single leaf is just new Tree(new Leaf()), while a tree contains three leaves might be new Tree(new Leaf(), new Leaf(), new Leaf()):

class Leaf {}

class Tree {

constructor(...children) {

this.children = children;

}

}

function countLeaves(tree) {

if (tree instanceof Tree) {

return tree.children.reduce(

(runningTotal, child) => runningTotal + countLeaves(child),

0

)

} else if (tree instanceof Leaf) {

return 1;

}

}

const sapling = new Tree(

new Leaf()

);

countLeaves(sapling)

//=> 1

const tree = new Tree(

new Tree(

new Leaf(), new Leaf()

),

new Tree(

new Tree(

new Leaf()

),

new Tree(

new Leaf(), new Leaf()

),

new Leaf()

)

);

countLeaves(tree)

//=> 6

This is a classic divide-and-conquer: Divide a tree up into its children, and count the leaves in child, then sum them to get the count of leaves in the tree.

For the vast majority of cases, recursive algorithms are just fine. This is especially true when the form of the algorithm matches the form of the data being manipulated. A recursive algorithm to “fold” the elements of a tree makes a certain amount of sense because the definition of a tree is itself recursive: A tree is either a left or another tree. And the function we just saw either returns 1 or the count of leaves in a tree.

But sometimes people want iterative algorithms. It could be that recursion eats up to much stack space, and they would rather consume heap space. It could be that they just don’t like recursive algorithms. Or… Who knows? Our purpose here is not to fall down a hole of discussing performance and optimization, we’d rather fall down a hole of exploring what kinds of interesting techniques we might use to transform recursion into iteration.

Let’s start with the simplest, and one that works remarkably well:

1: hide the recursion with iterators

Our algorithm above interleaves the mechanics of visiting every node in a tree with the particulars of what we want to do with leaf nodes. Let’s say that we want to be able to express that countLeaves is all about counting the number of nodes with a non-null leaf property, but we don’t want to clutter that up with recursion.

The easiest way to do that is to keep using recursion, but separate the concern of how to visit all the nodes in a tree from the concern of what we want to do with them. In JavaScript, we can make our trees into Iterables:

class Tree {

constructor(...children) {

this.children = children;

}

*[Symbol.iterator]() {

for (const child of this.children) {

yield child;

if (child instanceof Tree) {

yield* child;

}

}

}

}

function countLeaves(tree) {

let runningTotal = 0;

for (const child of tree) {

if (child instanceof Leaf) {

++runningTotal;

}

}

return runningTotal

}

Notice now that countLeaves is iterative. The recursion has been pushed into Tree’s iterator. It’s still recursive in the whole, but the code that knows how to count leaves is certainly iterative.

Furthermore, this lets us mix-and-match different collection types. Here’s a basket of yard waste:

class Twig {}

const yardWaste = new Set([

new Leaf(),

new Leaf(),

new Leaf(),

new Twig(),

new Twig()

])

countLeaves(yardWaste)

//=> 3

And of course, we can apply functions over iterables, for example:

function count (iterable) {

let runningTotal = 0;

for (const _ of iterable) {

++runningTotal;

}

return runningTotal;

}

function filter * (predicateFunction, iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

if (predicateFunction(element)) {

yield element;

}

}

}

function countLeaves (iterable) {

return count(

filter(

(element) => element instanceof Leaf,

iterable

)

);

}

This is great because our functions over iterables apply to a wide class of problems, not just recursive problems. So the takeaway is, one technique for turning recursive algorithms into iterative algorithms is to see whether we can recursively iterate. If so, separate the recursive iteration from the rest of the algorithm by writing an iterator.

2. abstract the recursion with higher-order recursive functions

Divide-and-conquer comes up a lot, but it’s not always directly transferrable to iteration. For example, we might want to recursively rotate a square. If we want to separate the mechanics of recursion from the “business logic” of rotating a square, we could move some of the logic into a higher-order function, multirec.

multirec is a template function that implements n-ary recursion:1

function mapWith (fn) {

return function * (iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

yield fn(element);

}

};

}

function multirec({ indivisible, value, divide, combine }) {

return function myself (input) {

if (indivisible(input)) {

return value(input);

} else {

const parts = divide(input);

const solutions = mapWith(myself)(parts);

return combine(solutions);

}

}

}

To use multirec, we plug four functions into its template:

- An

indivisiblepredicate function. It should report whether the problem we’re solving is too small to be divided. It’s simplicity itself for our counting leaves problem:node => node instanceof Leaf. - A

valuefunction that determines what to do with a value that is indivisible. For counting, we return1:leaf => 1 - A

dividefunction that breaks a divisible problem into smaller pieces.tree => tree.children - A

combinefunction that puts the result of dividing a problem up, back together.counts => counts.reduce((acc, c) => acc + c, 0)

Here we go:

const countLeaves = multirec({

indivisible: node => node instanceof Leaf,

value: leaf => 1,

divide: tree => tree.children,

combine: counts => [...counts].reduce((acc, c) => acc + c, 0)

})

Now, this does separate the implementation of a divide-and-conquer recursive algorithm from what we want to accomplish, but it’s still obvious that we’re doing a divide and conquer algorithm. Balanced against that, multirec can do a lot more than we can accomplish with a recursive iterator, like rotating squares, implementing HashLife, or even finding a solution to the Towers of Hanoi.

Speaking of the Towers of Hanoi… Not all recursive algorithms map neatly to recursive data structures. The recursive solution to the Towers of Hanoi is a good example. We’ll use multirec, demonstrating that we can separate the mechanics of recursion from our code for anything recursive, not just algorithms that work with trees. Let’s start with the function signature:

function hanoi (params) { // params = {disks, from, to, spare}

// ...

}

Our four elements will be:

- An

indivisiblepredicate function. In our case,({disks}) => disks == 1 - A

valuefunction that determines what to do with a value that is indivisible:({from, to}) => [from + " -> " + to] - A

dividefunction that breaks a divisible problem into smaller pieces.({disks, from, to, spare}) => [{disks: disks - 1, from, to: spare, spare: to}, {disks: 1, from, to, spare}, {disks: disks - 1, from: spare, to, spare: from}] - A

combinefunction that puts the result of dividing a problem up, back together.[...moves].reduce((acc, move) => acc.concat(move), [])

Like so:

const hanoi = multirec({

indivisible: ({disks}) => disks == 1,

value: ({from, to}) => [from + " -> " + to],

divide: ({disks, from, to, spare}) => [

{disks: disks - 1, from, to: spare, spare: to},

{disks: 1, from, to, spare},

{disks: disks - 1, from: spare, to, spare: from}

],

combine: moves => [...moves].reduce(

(acc, move) => acc.concat(move), [])

});

hanoi({disks: 3, from: 1, to: 3, spare: 2})

//=>

["1 -> 3", "1 -> 2", "3 -> 2",

"1 -> 3", "2 -> 1", "2 -> 3",

"1 -> 3"]

3. convert recursion to iteration with tail calls

Some recursive algorithms are much simpler than traversing a tree or generating solutions to the Towers of Hanoi. For example, the algorithm for computing Fibonacci numbers.

No, not that algorithm, the one we are thinking of involves matrix exponentiation, and you can read all about it here. In the middle of that algorithm, we have the need to multiply matrices by each other. We’ll repeat the same logic here, only using integers so that we can focus on the recursion.

Let’s start with a generic function for multiplying one or more numbers:

const multiply = (...numbers) => numbers.reduce((x, y) => x * y);

multiply(1, 2, 3, 4, 5)

//=> 120

If we want to find the exponent of a number, the naïve algorithm is to multiply it by itself repeatedly. We’ll use unnecessarily clever code to implement the trick, like this:

const multiply = (...numbers) => numbers.reduce((x, y) => x * y);

const repeat = (times, value) => new Array(times).fill(value);

const naivePower = (exponent, number) =>

multiply(...repeat(exponent, number));

naivePower(3, 2)

//=> 8

Besides the obvious of dropping down into the language’s library routines, there is a valuable optimization available. Exponentiation should not require “O-n” operations, it should be “O-log2-n.” We get there with recursion:

const power = (exponent, number) => {

if (exponent === 0) {

return 1;

} else {

const halfExponent = Math.floor(exponent / 2);

const extraMultiplier = exponent %2 === 0 ? 1 : number;

const halves = power(halfExponent, number);

return halves * halves * extraMultiplier;

}

}

power(16, 2)

//=> 65536

Instead of performing 15 multiplications, the recursive algorithm performs four multiplications. That saves a lot of stack, if that’s our concern with recursion. But there is an interesting opportunity here. The stack is needed because after power calls itself, it does a bunch more work before returning a result.

If we can find a way for power to avoid doing anything except returning the result of calling itself, we have a couple of optimizations available to ourselves. So let’s arrange things such that when power calls itself, it returns the result right away. The “one weird trick”” is to supply an extra parameter, so that the work gets done eventually, but not after power calls itself:2

const power = (exponent, number, acc = 1) => {

if (exponent === 0) {

return acc;

} else {

const halfExponent = Math.floor(exponent / 2);

const extraMultiplier = exponent %2 === 0 ? 1 : number;

return power(

halfExponent,

number * number,

acc * extraMultiplier

);

}

}

Our power functions recursion is now a tail call meaning that when it calls itself, it returns that result right away, it doesn’t do anything else with it. Because it doesn’t do anything with the result, behind the scenes the language doesn’t have to store a bunch of information in a stack frame. In essence, it can treat the recursive call like a GOTO instead of a CALL.

Many functional languages optimize this case. While our code may look like recursion, in such a language, our implementation of power it would execute in constant stack space, just like a loop.

Alas, tail calls in JavaScript have turned out to be a contentious issue. At the time of this writing, Safari is the only browser implementing tail call optimization. So, while this is a valid optimization in some languages, and might be useful for a Safari-only application in JavaScript, it would be nice if there was something useful we could do now that we’ve done all the work of transforming power into tail-recursive form.

Like… Convert it to a loop ourselves.

4. convert tail-recursive functions into loops

Here’s power again:

const power = (exponent, number, acc = 1) => {

if (exponent === 0) {

return acc;

} else {

const halfExponent = Math.floor(exponent / 2);

const extraMultiplier = exponent %2 === 0 ? 1 : number;

return power(

halfExponent,

number * number,

acc * extraMultiplier

);

}

}

If we don’t want to leave the tail call optimization up to the compiler, with a tail-recursive function there’s a simple transformation we can perform: We wrap the whole thing in a loop, we reassign the parameters rather than passing parameters, and we use continue instead of invoking ourselves.

Like this:

const power = (exponent, number, acc = 1) => {

while (true) {

if (exponent === 0) {

return acc;

} else {

const halfExponent = Math.floor(exponent / 2);

const extraMultiplier = exponent %2 === 0 ? 1 : number;

[exponent, number, acc] =

[halfExponent, number * number, acc * extraMultiplier];

continue;

}

}

}

The continue is superfluous, but when converting other functions it becomes essential. With a bit of cleaning up, we get:

const power = (exponent, number, acc = 1) => {

while (exponent > 0) {

const halfExponent = Math.floor(exponent / 2);

const extraMultiplier = exponent %2 === 0 ? 1 : number;

[exponent, number, acc] =

[halfExponent, number * number, acc * extraMultiplier];

}

return acc;

}

So we know that for a certain class of recursive function, we can convert it to iteration in two steps:

- Convert it to tail-recursive form.

- Convert the tail-recursive function into a loop that rebinds its parameters.

And presto, we get an algorithm that executes in constant stack space! Or do we?

Unfortunately, it is not always possible to execute a recursive function in constant space. power worked, because it is an example of linear recursion: At each step of the way, we execute on one piece of the bigger problem and then combine the result in a simple way with the rest of the problem.

Linearly recursive algorithms are often associated with lists. Every fold, unfold, filter and other algorithm can be expressed as linear recursion, and it can also be expressed as an iteration in constant space. But not all recursive algorithms are linear. Some are “n-ary,” where n > 1. In other words, at each step of the way they must call themselves more than once before combining the results.

Such algorithms can be transformed into loops, but the mechanism by which we store data to be worked on later will necessarily grow in some relation to the size of the problem.

5. implement multirec with our own stack

It is possible to convert n-ary recursive algorithms to iterative versions, but not in constant space. What we can do, however, is move the need for “stacking” our intermediate results and work to be done out of the system stack and into our own explicit stack. Let’s give it a try.

We could look at directly implementing something like Towers of Hanoi with a stack, but let’s maintain our separation of concerns. Instead of implementing Towers of Hanoi directly, we’ll implement multirec with a stack, and then trust that our existing Towers of Hanoi implementation will work without any changes.

That particular choice gives us the power of being able to express Towers of Hanoi as a divide-and-conquer algorithm, while implementing it using a stack on the heap. That’s terrific if our only objection to multirec is the possibility of a stack overflow.3

Our new multirec has its own stack, and is clearly iterative. It’s one big loop:

function multirec({ indivisible, value, divide, combine }) {

return function (input) {

const stack = [];

if (indivisible(input)) {

// the degenerate case

return value(input);

} else {

// the iterative case

const parts = divide(input);

const solutions = [];

stack.push({parts, solutions});

}

while (true) {

const {parts, solutions} = stack[stack.length - 1];

if (parts.length > 0) {

const subproblem = parts.pop()

if (indivisible(subproblem)) {

solutions.unshift(value(subproblem));

} else {

// going deeper

stack.push({

parts: divide(subproblem),

solutions: []

})

}

} else {

stack.pop(); // done with this frame

const solution = combine(solutions);

if (stack.length === 0) {

return solution;

} else {

stack[stack.length - 1].solutions.unshift(solution);

}

}

}

}

}

With this version of multirec, our Towers of Hanoi and countLeaves algorithms both have switched from being recursive to being iterative with their own stack. That’s the power of separating the specification of the divide-and-conquer algorithm from its implementation.

6. implementing depth-first iterators with our own stack

We can use a similar approach for iteration. Recall our Tree class:

class Tree {

constructor(...children) {

this.children = children;

}

*[Symbol.iterator]() {

for (const child of this.children) {

yield child;

if (child instanceof Tree) {

yield* child;

}

}

}

}

Writing an iterator for a recursive data structure was useful for hiding recursion in the implementation, and it was also useful because we have many patterns, library functions, and language features (like for..of) that operate on iterables. However, the recursive implementation uses the system’s stack.

What about using our own stack, as we did with multirec? That would produce a nominally iterative solution:

class Tree {

constructor(...children) {

this.children = children;

}

*[Symbol.iterator]() {

let stack = [...this.children].reverse();

while (stack.length > 0) {

const child = stack.pop();

yield child;

if (child instanceof Tree) {

stack = stack.concat([...child.children].reverse());

}

}

}

}

And once again, we have no need to change any function relying on Tree being iterable to get a solution that does not consume the system stack.

7. implementing breadth-first iterators with a queue

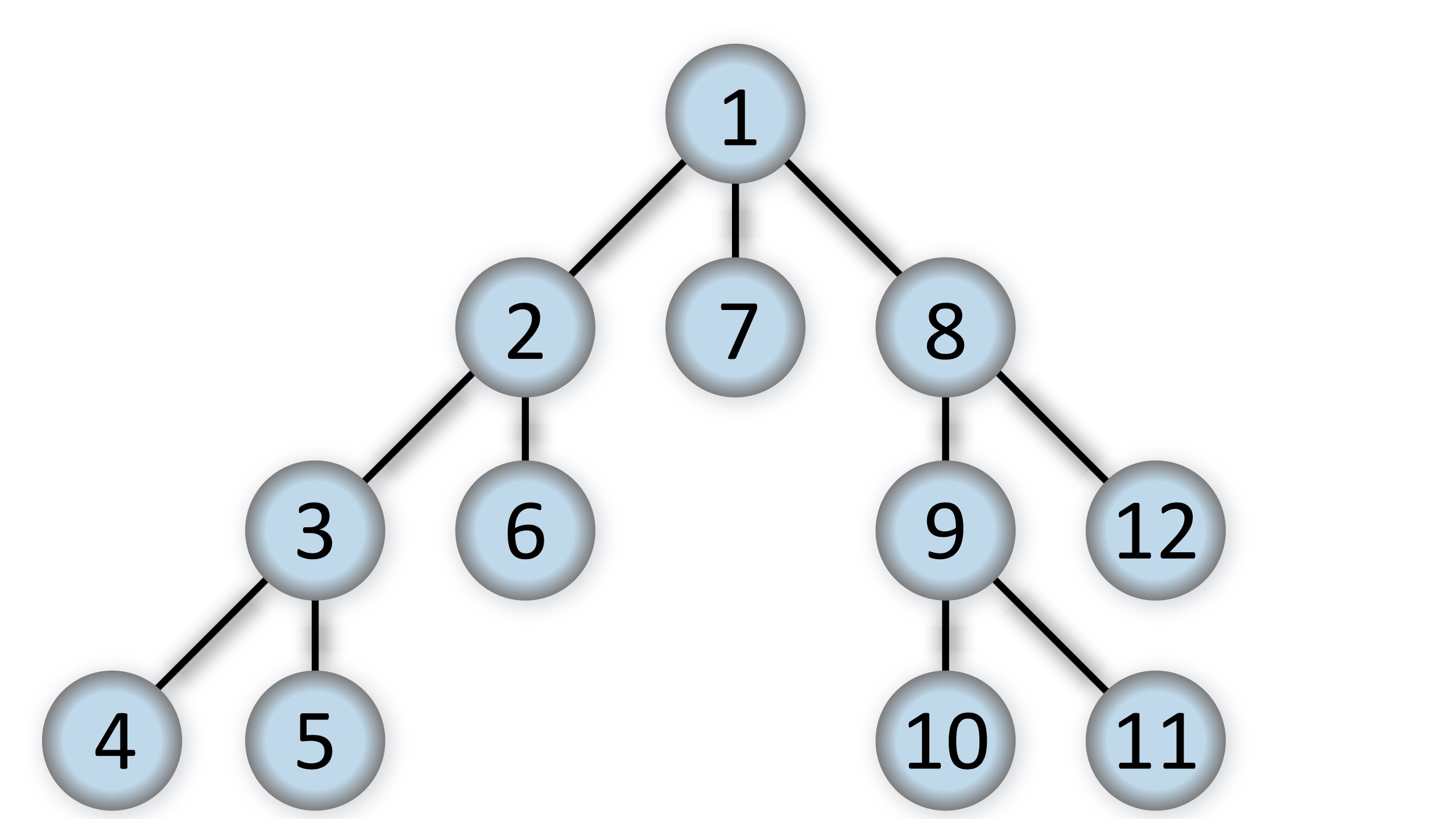

Our stack-based iterator performs a depth-first search:

By Alexander Drichel - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

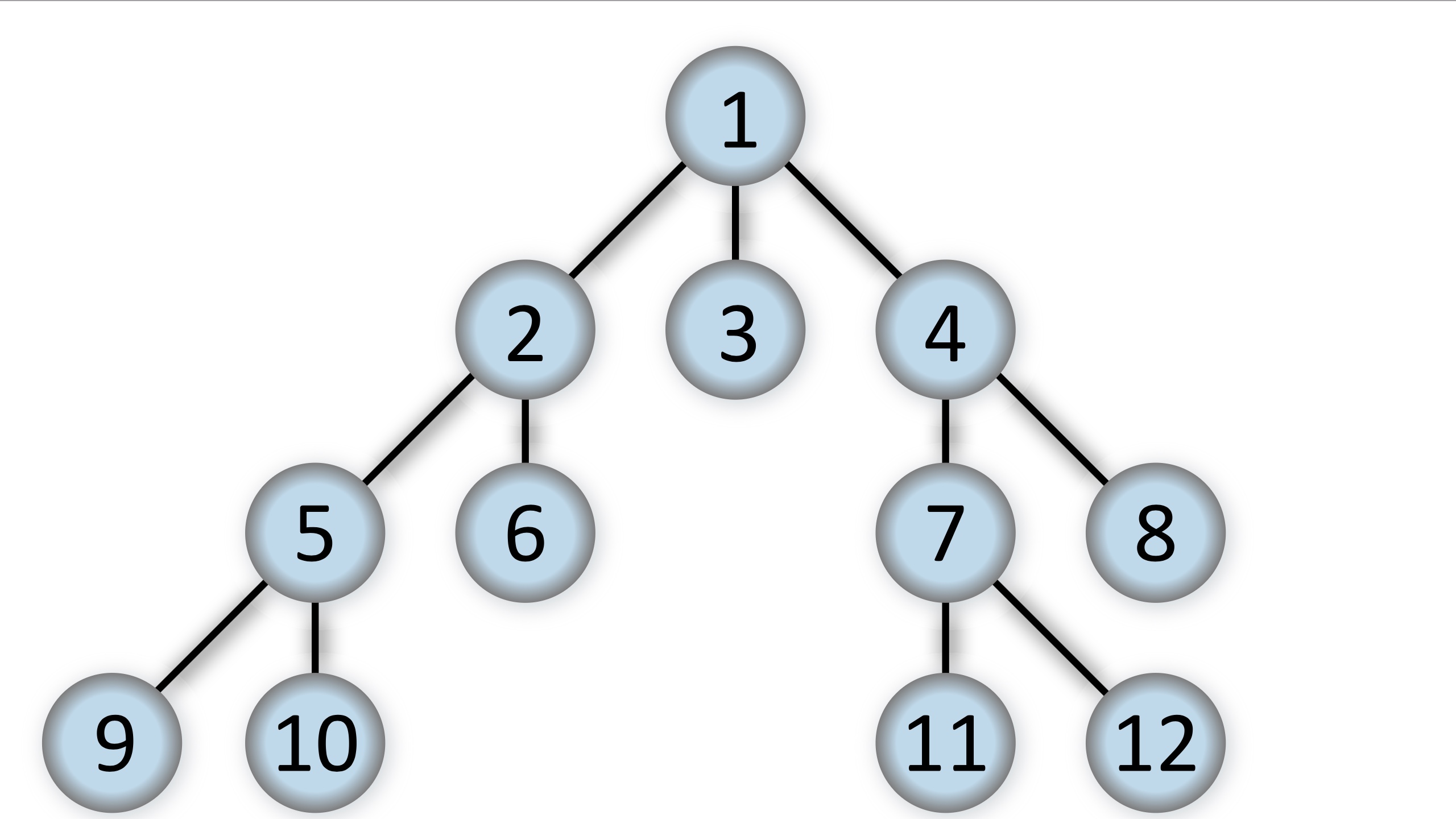

But for certain algorithms, we want to perform a breadth-first search:

By Alexander Drichel - Own work, CC BY 3.0

We can accomplish this using a queue instead of a stack:

class Tree {

constructor(...children) {

this.children = children;

}

*[Symbol.iterator]() {

let queue = [...this.children];

while (queue.length > 0) {

const child = queue.shift();

yield child;

if (child instanceof Tree) {

queue = queue.concat([...child.children]);

}

}

}

}

And once again, we have no need to change any function relying on Tree being iterable to get a solution that does not consume the system stack.

wrap-up

We’ve just seen seven different ways to get recursion out of our functions. The first two (“hide the recursion with iterators” and “abstract the recursion with higher-order recursive functions”) didn’t eliminate recursion altogether, but moved the recursion out of our code.

“Convert recursion to iteraction with tail calls” arranged our code such that a suitable programming language implementation would convert our recursive code into iteration automatically. “Convert tail-recursive functions into loops” showed how to do this manually for the case where the language wouldn’t do it for us, or if we’re allergic to recursion for other reasons.

The last three (“implement multirec with our own stack,” “implementing depth-first iterators with our own stack,” and “implementing breadth-first iterators with a queue”) showed how to manage our own storage when working with n-ary recursive algorithms. And we saw that by converting our iterators and multirec to iteration, we’d get iteration “for free” for all our other code, thanks to the refactoring in the first two approaches.

So now, if we’re ever in an interview and our interlocutor asks, “Can you convert this algorithm to use iteration,” we can reply, “Sure! But there are at least seven different ways to do that, depending upon what we want to accomplish…”4

(Discuss on reddit and hacker news. If you like this kind of thing, JavaScript Allongé is exactly the kind of thing you’ll like.)

notes

-

There is more about

multirec,linrec, and another function,binrec, in From Higher-Order Functions to Libraries And Frameworks. ↩ -

Refactoring recursive functions into “tail recursive functions” has been practiced from the early days of Lisp, and there are a number of practical techniques we can learn to apply. An excellent guide that touches on both tail-recursive refactoring and on converting recursion to iteration is Tom Moertel’s Tricks of the trade: Recursion to Iteration series. ↩

-

Many, many years ago, I wanted to implement a Towers of Hanoi solver in BASIC. The implementation I was using allowed calling subroutines, however subroutines were non-reëntrant. So it was impossible for a subroutine to invoke itself. I wound up implementing a stack of my own in an array, and that, as they say, was that. (You read this note correctly: Forty years ago, non-reëntrant subroutines were a thing in widely available implementations.) ↩

-

Actually there are at least two more, but this blog post is already long enough. I’ve written elsewhere about using trampolines to implement tail-call optimization in JavaScript, and then there is the deeply fascinating subject of conversion to continuation-passing style. ↩