Preface (2023)

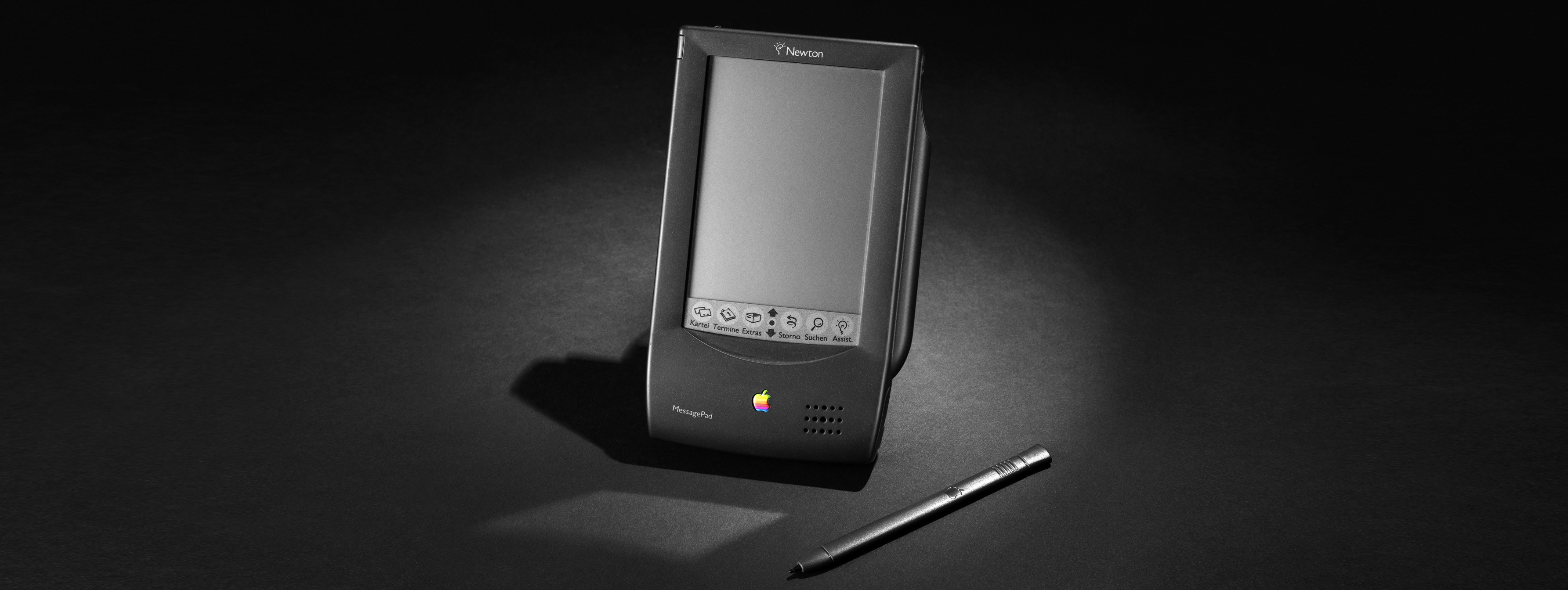

The following described the cryptographic protocol and algorithm used by nCrypt Light back in 1993-94. I wrote nCrypt Light in the hope of creating a strong cryptography app for the orginal Newton MessagePad 100. Rolling your own crypto is well-understood to be the complete opposite of implementing secure cryptography, so this is presented purely for nostalgia and amusement purposes.

The MessagePad at that time had messaging and email if connected to a network of some kind, but it did not have strong, secure protocol for ensuring the privacy of messages or documents. My business partner and I thought there might be a market for encrypting messages much as Telegram or Signal do today. Our first goal was to ship a symmetrical encryption app (where sender and receiver must share a passphrase as the secret), and he hoped to write a public-key app later.

Between other business commitments, quickly discovering how little I understood about cryptography, and the fact that the Newton did not become the next big platform, we never wrote another line of Newton code. I lost the source code (written in NewtonScript), but from time to time I look around and discover it’s still possible to download the app from FTP sites.

On the plus side, we uploaded it to various sites, one of which was CompuServe. A few months later, I received a cheque: Someone had not just downloaded our app, but paid us the optional USD 25 for it! That was the very first time something I wrote “on spec” for the world to try, made any money, and I still have the original physical cheque in my memory box.

And here is the original text, which has been hosted for all these years by Peter Conrad. You can find it here.

The description below is © 1994 CustomWare, Inc. and Reginald Braithwaite-Lee. That copyright overrides the create commons license that applies to the remainder of this blog. Note the use of pseudocode in the description: At the time, we were concerned that sharing source code directly could place us in jeopardy of the laws of the time, which considered cryptography a munition covered by strict export restrictions backed by draconian penalties for noncompliance.

Introduction

nCrypt Light (“nCrypt”) is a password protection application for the Apple Newton. A derivative application, incorporating public key cryptographic techniques, is currently being developed. nCrypt Light is an enabling architecture; cryptographic protocols are “installed” into nCrypt, and those protocols become available for users.

nCrypt’s architecture is composed of layers. At the highest level is the nCrypt application. nCrypt makes use of protocols. Protocols implement an algorithm and supporting procedures such as key generation, message padding, and error detection. Protocols make use of algorithms. At this time, nCrypt includes one protocol, the Alternating Stop and Go Generator (“Stop & Go”), built-in. Another, an implementation of Bruce Schneier’s Blowfish, is available as a “drop-in” module.

This document describes the Stop & Go protocol, with an emphasis on providing details useful to cryptanalysts searching for weaknesses. Notes indicatate where nCrypt’s implementation of Stop & Go differs from this description. Two future documents are planned:The first will describe nCrypt’s binary to text translation formats and the second will describe how developers may write other “drop-in” algorithms.

Both nCrypt (the Newton application) and the cryptographic algorithms used by nCrypt are works-in-progress. This document is published in order to foster analysis which will improve the the specific cryptographic techniques used in nCrypt as well as to improve Cryptography in general.

The Stop & Go protocol is constructed from independant modules. The most basic, the Secure Message Authentication Code (“SMAC”), is a key-dependant varient of NIST’s Secure Hash Algorithm (“SHA”). SMAC is used to build the Stop & Go algorithm. The keys needed for the Stop & Go protocol are generated from passphrases using a salt and SHA.

CustomWare hereby places its interest in the cryptographic techniques used in Stop & Go (“SMAC” and “Stop & Go”) in the public domain, with no restrictions on their use (CustomWare does not indemnify users from any consequences of such use: before proceeding, perform a thorough patent search and consult qualified legal counsel). nCrypt (the application) remains the proprietary property of CustomWare and may only be used and distributed as allowed by the license agreement accompanying nCrypt.

The Secure Message Authentication Code

The Secure Message Authentication Code (“SMAC”) is a modification of the Secure Hash Algorithm (“SHA”).[^1] SHA is an 80 round hash which securely compresses a 512 bit value to a 160 bit result. It is conjectured that:

Given any message, 2^160 operations are required to discover another message which generates the same hash result.

2^80 operations are required to find any two messages which generate the same hash value.

SHA makes use of five 32 bit buffers which are initialized to 0xa67452301, 0xEFCDAB89, 0x98BADCFE, 0x10325476, and 0xC3D2E1F0. The input material is repeatedly mixed into the buffer, then the original buffer contents are added (modulo 32) to the result. When more than one 512 bit block is to be hashed, the result of one block’s hash is used as the buffer for the next.

SMAC makes use of a 160 bit key, which is divided into five 32 bit buffers. The key is used instead of SHA’s initial buffer values. Every time SMAC is used to compress a 512 bit value to a 160 bit result, the internal buffers are reset to the key value. No other modification has ben made to the algorithm. SMAC’s keys are defined either as values produced by hashing bit strings with SHA, or as output from SMAC.

We conjecture that setting the internal buffers to cryptographically secure values produced by SHA or SMAC produces a hash which is as secure as SHA. Our reasoning is that this operation is equivalent to prepending SMAC’s inputs with key material before hashing.

The Alternating Stop and Go Generator Algorithm

The Alternating Stop and Go Generator (“Stop & Go”) is based on a stream cipher described by Schneier[^2] from a paper presented by Günther[^3]. Stop & Go uses three generators (“rL”, “rR”, & “rA”) constructed from SMACs. The output of Stop & Go is independant of the plaintext; it is a large generator which outputs 160 bits per round.

Each generator consists of a register and a SMAC function. The keys for all three generators in nCrypt are identical. If more key material is available, using independant keys could increase security. Also, generating separate keys by “expanding” a single key could increase security.

Each generator maintains its own 512 bit shift register. The registers are initially loaded as follows: rL is loaded with 0xFFFF...FFFF. rR is loaded with 0x0000...0000. rA is loaded with 0xAAAA...AAAA. (The generator shift registers should not be confused with SMAC’s internal register.) Stop & Go’s generators work by repeatedly “clocking:” clocking a generator generates a 160 bit result from the generator’s shift register. The shift register is the modified by discarding the first 160 bits and appending 160 bits of material.

Before any encryption is performed, the Stop & Go protocols requires that the plaintext be padded to a multiple of 512 bits. (The padding mechanism is unspecified; nCrypt’s implementation pads plaintext with a repeated byte value equal to the number of bytes of padding). Once the padding has been completed, all three generators are “clocked”. The results of rL & rR are XORed to produce a “mask.” The mask is XORed with the first block of plaintext to produce the first block of ciphertext.

For the second and each subsequent block of plaintext, a bit from the result of rA is used to determine whether to clock rL or rR.These “alternation” bits are taken from consecutive bit positions in rA’s result. The mask from the previous round is pushed through the generator’s shift register and a new result is obtained. The results from both generators (one new and one previous) are then XORed together to produce a new mask.

Should more than 160 blocks need to be encrypted, rA is clocked to produce 160 more bits for alternation. The first bit of rA’s new result is then used to clock rL or rR and the resulting mask is used for the next block of plaintext.

Generating Session Keys from Passphrases

Generating a Session Key

Session keys consist of five 32-bit values. Session keys should be unique for each message generated by the cipher. The Stop & Go protocol generates session keys for passphrase-protection by concatenating a passphrase with a unique salt and hashes the two together using SHA. The process is repeated a variable number of times and the result, a 160-bit value, is used as the session key. The number of iterations is not considered secure and is transmitted with the ciphertext.

The unique salt is the result returned by Newton’s TimeInSeconds() function, which is the number of seconds elapsed since Midnight, January 1, 1904. This number need not be secure and is transmitted with the ciphertext.

The Stop & Go protocol currently performs four iterations when encrypting, and can handle any number of iterations when decrypting. nCrypt’s implemntation of the Stop & Go protocol does not perform a fast passphrase check. After decrypting the entire ciphertext, the Stop & Go protocol checks the last block for well-formed padding. CustomWare has experimented with a fast passphrase check and may incorporate this feature into a future version of the Stop & Go protocol .

The Stop & Go protocol allows for variable effective keylengths from 8 to 160 bits, (for practical reasons, nCrypt’s implementation of the Stop & Go protocol restricts keylengths to multiples of 8). In all cases, the Stop & Go protocol generates a 160 bit session key using the method described above. When encrypting, the Stop & Go protocol checks the desired length and performs one of two operations:

- If 160 bits of effective keylength are required, the Stop & Go protocol uses the 160 bit session key as is and proceeds without further operations on the session key

- If fewer than 160 bits of effective keylength are required, the Stop & Go protocol truncates the session key to the desired length and hashes the truncated key with SHA. The resulting 160 bits are used as the session key

- The number of bits of effective keylength are not considered secure and are transmitted with the ciphertext.

nCrypt’s shareware implementation of the Stop & Go protocol only encrypts with 40 bits of effective keylength. It can decrypt messages created with any number of effective bits of keylength.

Cryptanalytic Comments

The basis for the security of Stop & Go is the conjecture that the difficulty of guessing the initial buffer value given a chosen SMAC register and a known output is as difficult as guessing a SMAC register given a known initial buffer and a known output. Could this conjecture be false?

Peter Gutman (pgut01@cs.aukuni.ac.nz) pointed out that rA and rB could enter the same state (i.e. their registers become identical) which would produce an extremely weak sequence. A possible improvement would be to check for this possibility and immediately clock again should this happen.

The XORing of rL and rR could assist an attacker using differential cryptanalysis.[^4]

Bill Stewart (bill.stewart@pleasantonca.ncr.com) suggested that the use of TimeInSeconds() as the salt value could be too limited a range of salt values; an attacker using a dictionary attack against a weak passphrase may not be sufficiently hampered if the range of possible salts is too small. A possible improvement would be to concatenate additional information to TimeInSeconds() such as the plaintext, a range of memory in the Newton, or other values and hash the result with SHA into a 160 bit salt. This may add significantly to the number of possible salt values and frustrate dictionary precomputation.

Bill Stewart also suggested incorporating passphrase material into each iteration of the session key generation process.

The use of highly regular initial registers for rL, rR and rA could assist an attacker in cryptanalizing the session key. Possible improvements would be:

- Expand the session key and use key material for the initial registers. We conjecture that this approach necessitates splitting the key material into parts which are generated separately: the key material used to generate the initial registers should be independant of the key material used to generate the keys for each generator.

- Abandon the SMAC functions and use SHA for all three generators, but expand the key material to fill the three registers with different initial states.

- Devise a “chosen register” attack in which an attacker can discover information about a SMAC’s registers from the result when the attacker gets to choose the input. Determine the worst possible register values for this type of attack and use those for the initial states.

- nCrypt is implemented on an Apple Newton MessagePad. The Newton’s “operating system” is completely dynamic and may relocate objects at any time, without warning. An attacker with access to a Newton used to generate ciphertext may be able to recover the plaintext or even the passphrase from RAM. For this reason, CustomWare suggest that nCrypt only be used to generate messages for secure transmission or storage on other systems.

PseudoCode

FUNCTION Stop&Go IS LAMBDA( paddedBinary, sessionKey, bitsInKey )

BEGIN

TEMPORARY i, j;

TEMPORARY mask BECOMES nil;

TEMPORARY resultL BECOMES nil;

TEMPORARY resultR BECOMES nil;

TEMPORARY alternationBits BECOMES -1;

TEMPORARY shiftRegisterL BECOMES NEW-BINARY( 64 );

TEMPORARY shiftRegisterR BECOMES NEW-BINARY( 64 );

TEMPORARY shiftRegisterA BECOMES NEW-BINARY( 64 );

FOR-EACH-VALUE-OF i BECOMES 0 TO 63 IN-STEPS-OF 2 DO BEGIN

shiftRegisterL AT i BECOMES 0x0000;

shiftRegisterR AT i BECOMES 0xFFFF;

shiftRegisterA AT i BECOMES 0xAAAA

END;

IF bitsInKey < 160 THEN

sessionKey BECOMES SecureHashOf( bitsInKey N-BITS-FROM sessionKey

AT 0 BITS);

TEMPORARY AA BECOMES 32-BITS-FROM sessionKey AT 0 BYTES;

TEMPORARY BB BECOMES 32-BITS-FROM sessionKey AT 4 BYTES;

TEMPORARY CC BECOMES 32-BITS-FROM sessionKey AT 8 BYTES;

TEMPORARY DD BECOMES 32-BITS-FROM sessionKey AT 12 BYTES;

TEMPORARY EE BECOMES 32-BITS-FROM sessionKey AT 16 BYTES;

TEMPORARY cryptBinary BECOMES NEW-BINARY( length(paddedBinary) );

TEMPORARY lenPadded BECOMES length(paddedBinary);

FOR-EACH-VALUE-OF i BECOMES 0 TO lenPadded-20 IN-STEPS-OF 20 DO

BEGIN

IF alternationBits < 0 THEN BEGIN

TEMPORARY resultA BECOMES SecureMACOf( AA, BB, CC, DD, EE,

shiftRegisterA );

DROP-20-BYTES-FROM shiftRegisterA;

APPEND resultA TO shiftRegisterA;

alternationBits BECOMES 159

END;

TEMPORARY switch BECOMES 1-BIT-FROM resultA AT alternationBits

BITS;

alternationBits BECOMES alternationBits - 1;

IF switch = 0 THEN

resultL BECOMES nil

else

resultR BECOMES nil;

IF LOGICAL-NOT resultL THEN BEGIN

IF mask THEN BEGIN

DROP-20-BYTES-FROM shiftRegisterL;

APPEND mask TO shiftRegisterL

END;

resultL BECOMES SecureMACOf( AA, BB, CC, DD, EE, shiftRegisterL );

END;

IF LOGICAL-NOT resultR THEN BEGIN

IF mask THEN BEGIN

DROP-20-BYTES-FROM shiftRegisterR;

APPEND mask TO shiftRegisterR

END;

resultR BECOMES SecureMACOf( AA, BB, CC, DD, EE, shiftRegisterR );

END;

mask BECOMES BITWISE-XOR( resultL, resultR );

cryptBinary FROM i TO i+19 BECOMES BITWISE-XOR( mask,

paddedBinary FROM i TO i+19 );

END;

RETURN cryptBinary

END

Bibliography

- “SHA: The Secure Hash Algorithm,” William Stallings, Dr. Dobb’s Journal, April 1994, pp. 32-34.

- “Applied Cryptography,” Bruce Schneier, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, pp. 360-361.

- “Alternating Step Generators Controlled by de Bruijn Sequences,” C. G. Gunther, Advances in Cryptology[EUROCRYPT ]87 Proceedsings, Springer-Verlag, 1988, pp. 5-14.

- “Differential Cryptanalysis,” Eli Bihem & Adi Shamir, Springer-Verlag, 1993