A few weeks ago, I ordered a copy of the Sesquicentennial Edition of The Annotated Alice.

As is their wont, Amazon’s collaborative filters showed me other books that might be of interest to me, and I spotted a copy of Knots and Borromean Rings, Rep-Tiles, and Eight Queens: Martin Gardner’s Unexpected Hanging.

I nearly gasped out loud, savouring the memory of one of the earliest computer programs that I ever wrote from scratch, a program that searched for solutions to the eight queens puzzle.

Prelude: 1972 – 1977

This prelude is long on nostalgia and short on programming. If that does not interest you, feel free to skip straight to the description of the eight queens puzzle.

In the nineteen-seventies, I spent a lot of time in Toronto’s libraries. My favourite hangouts were the Sanderson Branch (which was near my home in Little Italy), and the “Spaced Out Library,” a non-circulating collection of science fiction and fantasy donated by Judith Merril, that was housed within St. George and College Street branch.1

I especially enjoyed reading back issues of Scientific American, and like many, I was captivated by Martin Gardner’s “Mathematical Games” columns. My mother had sent me to a day camp for gifted kids once, and it was organized like a university. The “students” self-selected electives, and I picked one called “Whodunnit.” It turned out to be a half-day exercise in puzzles and games, and I was hooked.

Where else would I learn about playing tic-tac-toe in a hypercube? Or about liars and truth-tellers? Or, as it happened, about Martin Gardner? I suspect the entire material was lifted from his collections of columns, and that suited me down to the ground.

One day we had a field trip to the University of Toronto’s High-Speed Job Stream, located in the Sanford Fleming Building2. This was a big room that had a line printer on one side of it, a punch card reader on the other, and lots and lots of stations for punching your own cards.

To run a job, you typed out your program, one line per card, and then stuck a header on the front that told the batch job what kind of interpreter or compiler to use. Those cards were brightly coloured, and had words like WATFIV or SNOBOL printed on them in huge letters.

You put header plus program into the hopper at the back, waited, and when it emerged from the reader, collected your punch cards and headed over to the large and noisy line printer. When the IBM 360 got around to actually running your job, it would print the results for you, and you would head over to a table to review the output and–nearly all of the time for me–find the typo or bug, update your program, and start all over again.

You can see equipment like this in any computer museum, so I won’t go into much more detail. Besides, the mechanics of running programs as batch jobs was not the interesting thing about the High Speed Job Stream. The interesting thing about the High Speed Job Stream was that there was no restriction on running jobs. You didn’t need an account or a password. Nobody stood at the door asking for proof that you were an undergrad working on an assignment.

So I’d go over there on a summer day and write software, and sometimes, I’d try to write programs to solve puzzles.

school

In the autumn of 1976, I packed my bags and went to St. Andrew’s College, a boarding school. One of the amazing things about “SAC” was that they had an actual minicomputer on the campus. For the time, this was unprecedented. In Ontario’s public school system, it was possible to take courses in programming, but they nearly all involved writing programs by filling in “bubble cards” with a pencil and submitting jobs overnight.

At SAC, there was a Nova 1220 minicomputer in a room with–oh glorious day–four ancient teletype machines hooked up to it with what I now presume were serial ports. It had various operating modes that were set by loading a 5MB removable hard disk (It was a 12” platter encased in a big protective plastic shell), and rebooting the machine by toggling bootstrap instructions into the front panel.

The mode set up for student use was a four-user BASIC interpreter. It had 16KB of RAM (yes, you read that right), and its simple model partitioned the memory so that each user got 4KB to themselves. You could type your program into the teletype, and its output would print on a roll of paper.

Saving programs on disc was not allowed. The teletypes had paper tape interfaces on the side, so to save a program we would LIST the source with the paper tape on, and it would punch ASCII or EBDIC codes onto the tape. We’d tear it off and take it with us. Later, to reload a program, we’d feed the tape into the teletype and it would act as if we were typing the program anew.

4KB was enough for assignments like writing a simple bubble sort, but I had discovered David Ahl by this time, and programs like “Super Star Trek” did not fit in 4KB. There was a 16KB single-user disc locked in a cabinet alongside programs for tabulating student results.

In defiance of all regulation, I would go in late, pick the cupboard’s lock, remove the disc I wanted, and boot up single-user mode. I could then work on customizing Super Star Trek or write programs to solve puzzles. Curiously, I never tampered with the student records. I was a morally vacant vessel at that point in my life: I’m not going to tell you that I had a moral code about these things. I think the truth is that I just didn’t care about marks.

The Eight Queens Puzzle

One of the things I worked on at school was writing new games. I made a Maharajah and the Sepoys program that would play the Maharajah while I played the standard chess pieces. It could beat me, which was enough AI for my purposes.

This got me thinking about something I’d read in a Martin Gardner book, the Eight Queens Puzzle. As Wikipedia explains, “The eight queens puzzle is the problem of placing eight chess queens on an 8×8 chessboard so that no two queens threaten each other. Thus, a solution requires that no two queens share the same row, column, or diagonal.”

By this time I knew a little about writing “generate and test” algorithms, as well as a little about depth-first search from writing games (like “Maharajah and the Sepoys”) that performed basic minimax searches for moves to make. So I set about writing a BASIC program to search for solutions. I had no formal understanding of computational complexity and running time, but what if I wrote a program and left it running all night?

The “most pessimum” approach looks something like this (BASIC has a for... next construct, but close enough):

for (let i0 = 0; i0 <= 7; ++i0) {

for (let j0 = 0; j0 <= 7; ++j0) {

for (let i1 = 0; i1 <= 7; ++i1) {

for (let j1 = 0; j1 <= 7; ++j1) {

// ...lots of loops elided...

for (let i7 = 0; i7 <= 7; ++i7) {

inner: for (let j7 = 0; j7 <= 7; ++j7) {

const board = [

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."]

];

const queens = [

[i0, j0],

[i1, j1],

[i2, j2],

[i3, j3],

[i4, j4],

[i5, j5],

[i6, j6],

[i7, j7]

];

for (const [i, j] of queens) {

if (board[i][j] != '.') {

// square is occupied or threatened

continue inner;

}

for (let k = 0; k <= 7; ++k) {

// fill row and column

board[i][k] = board[k][j] = "x";

const vOffset = k - i;

const hDiagonal1 = j - vOffset;

const hDiagonal2 = j + vOffset;

// fill diagonals

if (hDiagonal1 >= 0 && hDiagonal1 <= 7) {

board[k][hDiagonal1] = "x";

}

if (hDiagonal2 >= 0 && hDiagonal2 <= 7) {

board[k][hDiagonal2] = "x";

}

}

}

console.log(diagramOf(queens));

}

}

// ...lots of loops elided...

}

}

}

}

function diagramOf (queens) {

const board = [

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."]

];

for (const [i, j] of queens) {

board[i][j] = "Q";

}

return board.map(row => row.join('')).join("\n");

}

I believe I tried that, left the program running overnight, and when I came in the next morning before school it was still running. It was searching 8^16 (or more accurately, 64^8) candidates for a solution, that’s 281,474,976,710,656 loops. Given the speed of that minicomputer, I suspect the program would still be running today.

This will seem very obvious today, but one broad classification of algorithms for solving a problem like this is that of searching for solutions. It’s not the only one, but it’s the one I tried back then, and the one we’re going to focus on today. When you have a search problem, there are two ways to solve it more quickly: Search faster, and search a smaller problem space.

Although I didn’t use such words, I grasped that my first priority was searching a smaller space. So I thought about it for a bit. Then I had an insight of sorts: If I could think of the board as a one-dimensional ordered list of squares, I could reason as follows. If I pick a square for the leftmost queen, every other queen would have to come to the right of that queen.

By induction that would follow for the third and every subsequent queen. That is different than the worst-case brute force algorithm: After it picks a square for the first queen, each of the other queens can be in any position before or after it. But if we’re iterating through all of the possible positions for the first queen, it follows that we will already have iterated over any position with a queen before the first.

So this approach would eliminate a lot of duplicate positions to consider.

Although I didn’t have the education to articulate the idea properly, I was reasoning that what I wanted to search was the space of the number combinations of choosing 8 squares from 64 possibilities. That reduces the search space from 64^8 down to 4,426,165,368 candidate positions. That’s 63,593 times smaller, a big deal.

Before we get into the code that implements the “combinations” approach, I’ll share what happened when I tested my conjecture using my clumsy code of the time…

digression: disaster strikes

As above, I had chosen not to halt the program when it found a solution. Perhaps I wanted to print all of the solutions. As it happened, my test code had a bug, but it didn’t manifest itself until the program was deeper into its search, and my “optimization” took it to the failure case more quickly.

But I didn’t know this, so I left the updated program running overnight, and once again returned before breakfast to see if it had found any solutions. When I entered the room, there was a horrible smell and a deafening clacking sound. The test function had failed at some point, and it was passing thousands of positions in rapid order.

The paper roll on the teletype had jammed at some point in the night and was no longer advancing, but the teletype had hammered through the paper and was hammering on the roller behind. Rolls of paper had emerged from the machine and lay in a heap around it. I consider it a very lucky escape that a spark hadn’t ignited the paper or its dust that hung in the air.

I shut everything down, cleaned up as best I could, and then set about finding the bug. Although I never did cause another “physical crash,” it took me days (or possibly weeks, I don’t quite remember, and I did have other things going on at the time) before I had improved my program to the point where it found solutions.

refactoring before rewriting

Now back to writing out an improved algorithm based on combinations rather than the most pessimum approach.

One of our go-to techniques for modifying programs is to begin my making sure that the thing we wish to change is refactored into its own responsibility, then we can make a change to just one thing. The code from above has the generating loops and testing code thrown together all higgledy-piggledy. That makes it awkward to change the generation or the testing independently.

We might begin be refactoring the code into a generator and consumer pattern. The generator lazily enumerates the search space, and the consumer filters it to select solutions:3

function * mostPessimumGenerator () {

for (let i0 = 0; i0 <= 7; ++i0) {

for (let j0 = 0; j0 <= 7; ++j0) {

for (let i1 = 0; i1 <= 7; ++i1) {

for (let j1 = 0; j1 <= 7; ++j1) {

// ...lots of loops elided...

for (let i7 = 0; i7 <= 7; ++i7) {

for (let j7 = 0; j7 <= 7; ++j7) {

const queens = [

[i0, j0],

[i1, j1],

[i2, j2],

[i3, j3],

[i4, j4],

[i5, j5],

[i6, j6],

[i7, j7]

];

yield queens;

}

}

// ...lots of loops elided...

}

}

}

}

}

function test (queens) {

const board = [

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."],

[".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."]

];

for (const [i, j] of queens) {

if (board[i][j] != '.') {

// square is occupied or threatened

return false;

}

for (let k = 0; k <= 7; ++k) {

// fill row and column

board[i][k] = board[k][j] = "x";

const vOffset = k-i;

const hDiagonal1 = j - vOffset;

const hDiagonal2 = j + vOffset;

// fill diagonals

if (hDiagonal1 >= 0 && hDiagonal1 <= 7) {

board[k][hDiagonal1] = "x";

}

if (hDiagonal2 >= 0 && hDiagonal2 <= 7) {

board[k][hDiagonal2] = "x";

}

board[i][j] = "Q";

}

}

return true;

}

function * filterWith (predicateFunction, iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

if (predicateFunction(element)) {

yield element;

}

}

}

function first (iterable) {

const [value] = iterable;

return value;

}

const solutionsToEightQueens = filterWith(test, mostPessimumGenerator());

diagramOf(first(solutionsToEightQueens))

//=> ...go to bed and catch some 💤...

With this in hand, we can make a faster “combinations” generator, and we won’t have to work around any of the other code.

the “combinations” algorithm

An easy way to implement choosing combinations of squares is to work with numbers from 0 to 63 instead of pairs of indices. Here’s a generator that does the exact thing we want:

function * mapWith (mapFunction, iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

yield mapFunction(element);

}

}

function * choose (n, k, offset = 0) {

if (k === 1) {

for (let i = 0; i <= (n - k); ++i) {

yield [i + offset];

}

} else if (k > 1) {

for (let i = 0; i <= (n - k); ++i) {

const remaining = n - i - 1;

const otherChoices = choose(remaining, k - 1, i + offset + 1);

yield * mapWith(x => [i + offset].concat(x), otherChoices);

}

}

}

choose(5, 3)

//=>

[0, 1, 2]

[0, 1, 3]

[0, 1, 4]

[0, 2, 3]

[0, 2, 4]

[0, 3, 4]

[1, 2, 3]

[1, 2, 4]

[1, 3, 4]

[2, 3, 4]

We can now write choose(64, 8) to get all the ways to choose eight squares, and [Math.floor(n/8), n % 8] to convert a number from 0 to 63 into a pair of indices between 0 and 7:

const numberToPosition = n => [Math.floor(n/8), n % 8];

const numbersToPositions = queenNumbers => queenNumbers.map(numberToPosition);

const combinationCandidates = mapWith(numbersToPositions, choose(64, 8));

const solutionsToEightQueens = filterWith(test, combinationCandidates);

diagramOf(first(solutionsToEightQueens))

//=> ...go to bed and catch some 💤...

4,426,165,368 candidate solutions is still a tremendous size of space to search. It was definitely beyond my 1977 hardware.

But we can get faster. If we list the candidates out, we can see some of the problems right away. For example, the very first combination it wants to test is [[0, 0], [0, 1], [0, 2], [0, 3], [0, 4], [0, 5], [0, 6], [0, 7]]. The queens are all on the same row!

There is an easy fix for this and as a bonus, it gets us solutions really fast.

tree searching

In my original BASIC program way back in 1977, I built the board as I went, and marked the “threatened” squares. But instead of iterating over all the possible queen positions, as I added queens to the board I iterated over all the open positions. So after placing the first queen in the first open space, my board looked conceptually like this:

Qxxxxxxx

xx......

x.x.....

x..x....

x...x...

x....x..

x.....x.

x......x

The next queen I would try would be in the first “open” square, like this:

Qxxxxxxx

xxQxxxxx

xxxx....

x.xxx...

x.x.xx..

x.x..xx.

x.x...xx

x.x....x

I’d continue like this until there were eight queens, or I ran out of empty spaces. If I failed, I’d backtrack and try a different position for the last queen. If I ran out of different positions for the last queen, I’d try a different position for the second-to-last queen, and so on. This eliminated the problem of testing candidate solutions like [[0, 0], [0, 1], [0, 2], [0, 3], [0, 4], [0, 5], [0, 6], [0, 7]], because having placed [0,0], the next queen could not be placed on any square until [1, 2].

I did not know the words for it, but I was performing a depth-first search of a “tree” of positions. I was trying to find a path that was eight queens deep. And I was keeping the board updated to do so.

This method is interesting, because it is an “inductive” method that lends itself to recursive thinking. We begin with the solution for zero queens, and empty board. Then we successively search for ways to add one more queen to whatever we already have, backtracking if we run out of available spaces.

We can be clever in some ways. for example, we need only ever mark squares that come after the queen we are placing, as we never check any square earlier than the last queen we placed. Here’s an implementation similar to my 1977 approach, implemented as a class just to prove that we aren’t dogmatic about using functions for everything:

const OCCUPATION_HELPER = Symbol("occupationHelper");

class Board {

constructor () {

this.threats = [

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0

];

this.queenIndices = [];

}

isValid (index) {

return index >= 0 && index <= 63;

}

isAvailable (index) {

return this.threats[index] === 0;

}

isEmpty () {

return this.queenIndices.length === 0;

}

isOccupiable (index) {

if (this.isEmpty()) {

return this.isValid(index);

} else {

return this.isValid(index) && index > this.lastQueen() && this.isAvailable(index);

}

}

numberOfQueens () {

return this.queenIndices.length

}

hasQueens () {

return this.numberOfQueens() > 0;

}

queens () {

return this.queenIndices.map(index => [Math.floor(index / 8), index % 8]);

}

lastQueen () {

if (this.queenIndices.length > 0) {

return this.queenIndices[this.queenIndices.length - 1];

}

}

* availableIndices () {

for (let index = (this.isEmpty() ? 0 : this.lastQueen() + 1); index <= 63; ++index) {

if (this.isAvailable(index)) {

yield index;

}

}

}

[OCCUPATION_HELPER] (index, action) {

const [row, col] = [Math.floor(index / 8), index % 8];

// the rest of the row

const endOfTheRow = row * 8 + 7;

for (let iThreatened = index + 1; iThreatened <= endOfTheRow; ++iThreatened) {

action(iThreatened);

}

// the rest of the column

const endOfTheColumn = 56 + col;

for (let iThreatened = index + 8; iThreatened <= endOfTheColumn; iThreatened += 8) {

action(iThreatened);

}

// diagonals to the left

const lengthOfLeftDiagonal = Math.min(col, 7 - row);

for (let i = 1; i <= lengthOfLeftDiagonal; ++i) {

const [rowThreatened, colThreatened] = [row + i, col - i];

const iThreatened = rowThreatened * 8 + colThreatened;

action(iThreatened);

}

// diagonals to the right

const lengthOfRightDiagonal = Math.min(7 - col, 7 - row);

for (let i = 1; i <= lengthOfRightDiagonal; ++i) {

const [rowThreatened, colThreatened] = [row + i, col + i];

const iThreatened = rowThreatened * 8 + colThreatened;

action(iThreatened);

}

return this;

}

occupy (index) {

const occupyAction = index => {

++this.threats[index];

};

if (this.isOccupiable(index)) {

this.queenIndices.push(index);

return this[OCCUPATION_HELPER](index, occupyAction);

}

}

unoccupy () {

const unoccupyAction = index => {

--this.threats[index];

};

if (this.hasQueens()) {

const index = this.queenIndices.pop();

return this[OCCUPATION_HELPER](index, unoccupyAction);

}

}

}

The Board class does nearly all the work. But here’s the function that finds solutions:

function * inductive (board = new Board()) {

if (board.numberOfQueens() === 8) {

yield board.queens();

} else {

for (const index of board.availableIndices()) {

board.occupy(index);

yield * inductive(board);

board.unoccupy();

}

}

}

Very simple, and it shows at a high level exactly how things work. This inductive approach is a big step forward over combinations: With no further improvements or pruning, it tries 118,968 queen placements, a forty-thousandfold improvement over the 4,426,165,368 candidates of the combinations approach. It still is a little wasteful. For example, more than 42,000 of those placements involve placing the first queen on indices 8 or later, which means the first row is empty, and none of them will ever work. It’s just spinning its wheels after finding all 92 positions.

Also, and unlike our true generate-and-test approach, it interleaves partial generation with testing, so it’s not possible to break it into two separate pieces. A more subtle problem is this: By identifying the places in which we were trying to “choose” positions or look for “permutations” of positions, we were able to extract single responsibilities, and make them explicit with names.

It’s also a lot more complex, mostly because it’s mutating a single board in place rather than working with immutable data structures.

But even so, checking 118,968 placements is quite achievable, even on 1977 hardware. We’ve broken out of theory and into practice. But we can get faster!

the “rooks” algorithm

Let’s digress and consider a simpler problem. What are all the ways that eight rooks can be placed on a chessboard such that they don’t threaten each other?

Obviously, no two rooks can be on the same column or row. So the “aha!” realization is that we want all the combinations of eight positions which have a unique column and a unique row.

Let’s start with the unique rows. Every time we generate a set of rooks, one will be on row 0, one on row 1, one on row 2, and so forth. So the candidate solutions can always be arranged to look like this:

[

[0, ?], [1, ?], [2, ?], [3, ?], [4, ?], [5, ?], [6, ?], [7, ?]

]

Now what about the columns? Since no two rooks can share the same column, the candidate solutions must all have a unique permutation of the numbers 0 through 7, something like this:

[

[?, 3], [?, 1], [?, 5], [?, 6], [?, 4], [?, 2], [?, 0], [?, 7]

]

We’ll need to be able to generate the permutations of the column numbers from 0 to 7, and assign them to the rows 0 through 7 in order. That way, each candidate will look something like this:

[

[0, 3], [1, 1], [2, 5], [3, 6], [4, 4], [5, 2], [6, 0], [7, 7]

]

It’s fairly easy to generate arbitrary permutations4 if we don’t mind splicing and reassembling arrays:

function * permutations (arr, prefix = []) {

if (arr.length === 1) {

yield prefix.concat(arr);

} else if (arr.length > 1) {

for (let i = 0; i < arr.length; ++i) {

const chosen = arr[i];

const remainder = arr.slice(0, i).concat(arr.slice(i+1, arr.length))

yield * permutations(remainder, prefix.concat([chosen]));

}

}

}

permutations([1, 2, 3])

//=> [1, 2, 3], [1, 3, 2], [2, 1, 3], [2, 3, 1], [3, 1, 2], [3, 2, 1]

And now we can apply our permutations generator to generating candidate solutions to the rooks problem:

const solutionsToEightRooks = mapWith(

ii => ii.map((i, j) => [i, j]),

permutations([0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7])

);

Array.from(solutionsToEightRooks).length

//=> 40320

How do we apply this to solving the eight queens problem? Well, the set of all solutions to the eight queens problem is a subset of the set of all solutions to solving the eight rooks problem, so let’s search the set of all solutions to the eight rooks problem, and cut the search space down from 118,968 to 40,320!

const solutionsToEightQueens = filterWith(test, solutionsToEightRooks);

diagramOf(first(solutionsToEightQueens))

//=>

Q.......

......Q.

....Q...

.......Q

.Q......

...Q....

.....Q..

..Q.....

This is great! We’ve made a huge performance improvement simply by narrowing the “search space.” We’re down to 8! permutations of queens on unique rows and columns, just 40,320 different permutations to try.

programming digression: speeding up the testing

We’ve certainly sped things up by being smarter about the candidates we submit for testing. But what about the testing itself? The algorithm of filling in squares on a chess board very neatly matches how we might do this mentally, but it is quite slow. How can we make it faster?

For starters, if we know that we are only submitting solutions to the “eight rooks” problem, we need never test whether queens threaten each other on rows and columns. That cuts our testing workload roughly in half!

But what about diagonal attacks? Observe:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

If we sum the row and column number (row + col), we get a number representing the position of one of a queen’s diagonals. We can thus use:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

Instead of the entire chessboard! Simply compute the diagonal number for each queen and put an ‘x’ in this one-dimensional array. That’s much faster than putting an ‘x’ in every square of a diagonal.

What about the other diagonal?

| 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 |

| 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

Ah! We can sum the row with the inverse of the column number (row + 7 - col). If we use two of these one-dimensional arrays, we can check both diagonal attacks much more quickly than tediously marking chessboard squares. Like this:

function testDiagonals (queens) {

const nesw = [".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."];

const nwse = [".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", ".", "."];

if (queens.length < 2) return true;

for (const [i, j] of queens) {

if (nwse[i + j] !== '.' || nesw[i + 7 - j] !== '.') return false;

nwse[i + j] = 'x';

nesw[i + 7 - j] = 'x';

}

return true;

}

const solutionsToEightQueens = filterWith(testDiagonals, solutionsToEightRooks);

diagramOf(first(solutionsToEightQueens))

//=>

Q.......

......Q.

....Q...

.......Q

.Q......

...Q....

.....Q..

..Q.....

Checking diagonals without filling in squares is a specialized optimization, of course.5 Now we have coupled the test with the generation algorithm. In a larger software project, we might decouple things so that we can use them in different places in different ways.

But when we come along to optimize something like this, the coupling makes it harder to reuse components, and it makes the program harder to change. Luckily for us, this isn’t an essay about writing large software projects.

tree searching solutions to the rooks problem

The code we wrote for generating solutions to the rooks problem enumerates every permutation of eight squares that don’t share a common row or column. But many of those, of course, share a diagonal. For example, here are the first eight solutions it generates:

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [5, 5], [6, 6], [7, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [5, 5], [7, 6], [6, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [6, 5], [5, 6], [7, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [6, 5], [7, 6], [5, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [7, 5], [5, 6], [6, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [4, 4], [7, 5], [6, 6], [5, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [5, 4], [4, 5], [6, 6], [7, 7]]

[[0, 0], [1, 1], [2, 2], [3, 3], [5, 4], [4, 5], [7, 6], [6, 7]]

We can see at a glance that any solution beginning with [0,0], [1,1] is not going to work, so why bother generating all of the myriad candidates that are disqualified from the very first thing we check?

If we think of the rooks code as generating a tree of candidate positions rather than a flat list, we can adapt it for the eight queens problem by checking partial solutions as we go, and pruning entire subtrees that couldn’t possibly work. In essence, we’re combining my original tree search with the rooks solution that I didn’t know about.

This algorithm builds solutions one row at a time, iterating over the open columns, and checking for diagonal attacks. If there are none, it recursively calls itself to add another row. When it reaches eight rows, it yields the solution. It finds all 92 solutions by searching just 5,508 positions (Of which eight are the degenerate case of having just one queen on the first row):

const without = (array, element) =>

array.filter(x => x !== element);

function * inductiveRooks (

queens = [],

candidateColumns = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7]

) {

if (queens.length === 8) {

yield queens;

} else {

for (const chosenColumn of candidateColumns) {

const candidateQueens = queens.concat([[queens.length, chosenColumn]]);

const remainingColumns = without(candidateColumns, chosenColumn);

if (testDiagonals(candidateQueens)) {

yield * inductiveRooks(candidateQueens, remainingColumns);

}

}

}

}

This has the best of both worlds: It takes advantage of the “rooks” optimization and the “inductive” approach to pruning subtrees. And although it isn’t a pure pipeline, it does break the generation apart from the testing. So it’s not only faster, it’s also simpler.

I wish I’d thought of this approach in 1977!

bonus: exploiting symmetry

Something else comes to mind when thinking about reducing the size of the tree to search. There is symmetry to the queen moves, and as a consequence, the positions we find have rotational symmetry, and they also have reflective symmetry on either horizontal or vertical axes.

One way to exploit this begins with noting that every valid arrangement also has another valid arrangement that is symmetrical under vertical reflection, like these two mirror images of each other:

Q....... .......Q

......Q. .Q......

....Q... ...Q....

.......Q Q.......

.Q...... ......Q.

...Q.... ....Q...

.....Q.. ..Q.....

..Q..... .....Q..

Thus, every time we discover a valid arrangement, we can go ahead and make a vertical mirror image of it. That saves us work if we can also avoid generating and testing that mirror image arrangement.

So the $64,000 question is, “Can we avoid the work of generating both positions and their mirror images?”

Note the following numbered positions:

1234....

........

........

........

........

........

........

........

The “inductive” approach calculates every possible arrangement that has a queen in position 1 before computing those with a queen in position 2, then 3, then 4. When it has done so, it has computed half of the possible arrangements. But as we noted above, we can simply make a mirror image copy of each solution found, and thus we do not need to search all of the possible mirror arrangements.

Therefore, when we have searched all of the arrangements with a queen in positions one through four, we have essentially already searched all of these arrangements as well:

....4321

........

........

........

........

........

........

........

We thus know every possible solution that has a queen in one of the first four squares, plus every possible solution that does not have a queen in any of the first four squares. This is every possibility, and we need compute no further. Therefore, we can cut the search in half simply by only doing half the work, and then reflecting the solutions:

function * halfInductive () {

for (const candidateQueens of [[[0, 0]], [[0, 1]], [[0, 2]], [[0, 3]]]) {

yield * inductive(candidateQueens);

}

}

function verticalReflection (queens) {

return queens.map(

([row, col]) => [row, 7 - col]

);

}

function * flatMapWith (fn, iterable) {

for (const element of iterable) {

yield * fn(element);

}

}

const withReflections = flatMapWith(

queens => [queens, verticalReflection(queens)], halfInductive());

Array.from(withReflections).length

//=> 92

Now we’re really getting lazy: We only have to evaluate 2,750 candidate positions, a far, far smaller number than the original worst-case, most-pessimum, 281,474,976,710,656 tests. How much smaller? One hundred billion times smaller!

Mind you, a fairer comparison is to the combinations approach, which required 4,426,165,368 tests. A tree of 2,750 candidate positions is more than 1.5 million times smaller. We’ll take it!6

obtaining fundamental solutions

Now that we’ve had a look at exploiting vertical symmetry to do less work but still generate all of the possible solutions, including those that are reflections and rotations of each other, what about going the other way?

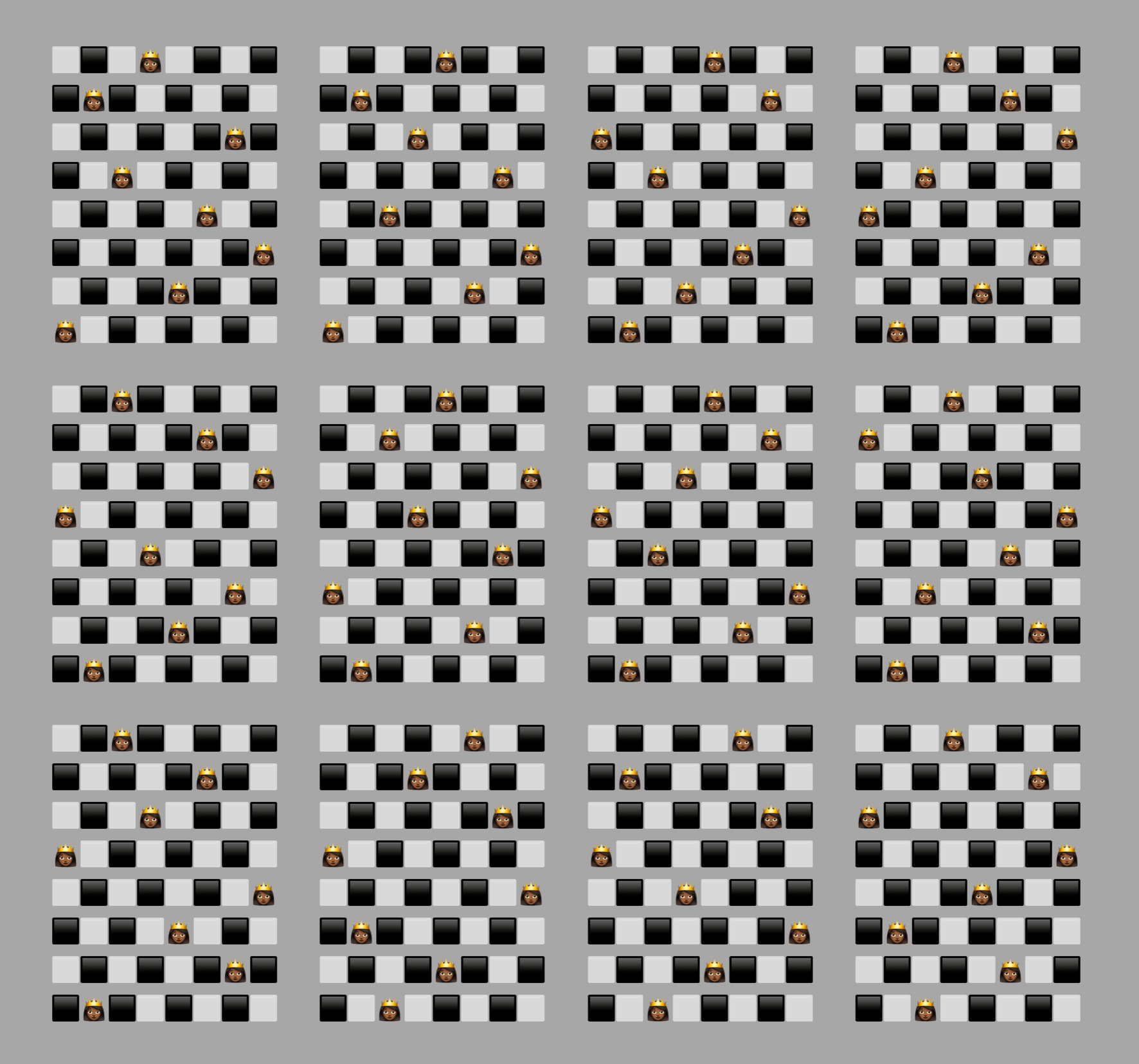

As Wikipedia explain, “If solutions that differ only by the symmetry operations of rotation and reflection of the board are counted as one, the puzzle has 12 solutions. These are called fundamental solutions.”

If we only want the fundamental solutions, we can filter the solutions we generate by testing them against a set that includes reflections and rotations. We obviously won’t actually output reflections and rotations, we’re just using them to filter the results:

const sortQueens = queens =>

queens.reduce(

(acc, [row, col]) => (acc[row] = [row, col], acc),

[null, null, null, null, null, null, null, null]

);

const rotateRight = queens =>

sortQueens( queens.map(([row, col]) => [col, 7 - row]) );

const rotations = solution => {

const rotations = [null, null, null];

let temp = rotateRight(solution);

rotations[0] = temp;

temp = rotateRight(temp);

rotations[1] = temp;

temp = rotateRight(temp);

rotations[2] = temp;

return rotations;

}

const indexQueens = queens => queens.map(([row, col]) => `${row},${col}`).join(' ');

function * fundamentals (solutions) {

const solutionsSoFar = new Set();

for (const solution of solutions) {

const iSolution = indexQueens(solution);

if (solutionsSoFar.has(iSolution)) continue;

solutionsSoFar.add(iSolution);

const rSolutions = rotations(solution);

const irSolutions = rSolutions.map(indexQueens);

for (let irSolution of irSolutions) {

solutionsSoFar.add(irSolution);

}

const vSolution = verticalReflection(solution);

const rvSolutions = rotations(vSolution);

const irvSolutions = rvSolutions.map(indexQueens);

for (let irvSolution of irvSolutions) {

solutionsSoFar.add(irvSolution);

}

yield solution;

}

}

function niceDiagramOf (queens) {

const board = [

["⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️"],

["⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️"],

["⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️"],

["⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️"],

["⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️"],

["⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️"],

["⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️"],

["⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️", "⬛️", "⬜️"]

];

for (const [row, col] of queens) {

board[7 - row][col] = "👸🏾";

}

return board.map(row => row.join('')).join("\n");

}

mapWith(niceDiagramOf, fundamentals(halfInductive()))

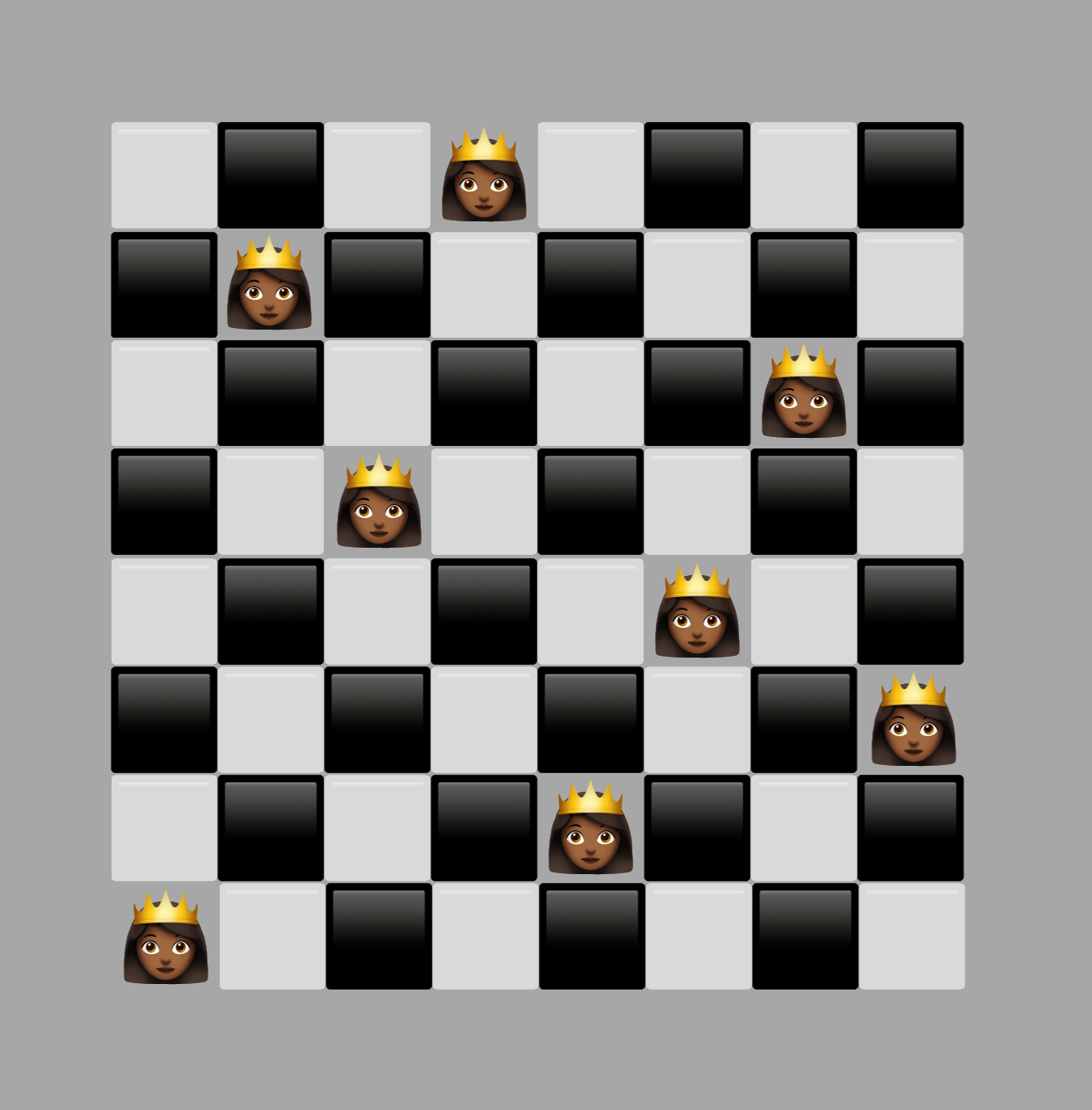

Success!!! If we want to check them against the fundamental solutions listed in Wikipedia, our algorithm outputs them in this order (some are rotations or reflections of the solution as displayed in Wikipedia):

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 12 | 10 | 11 |

And so to bed…

It was a lot of fun to revisit Martin Gardner’s column on the eight queen’s problem, and especially to rewrite these algorithms forty years later. It was neat to look at everything again with fresh eyes, and to see how we could go from searching 281,474,976,710,656, to 4,426,165,368, to 40,320, to 5,508, and finally to 2,750 candidate positions.

This post doesn’t have a deep insight into program design, and thus there’s no major point to summarize. Just as there can be recreational mathematics, there can be recreational programming. And that’s a very fine thing to enjoy.

Thank you, and good night!

Code

Notes

-

Of particular interest to me was that the Spaced Out Library also contained a collection of sci-fi themed wargames. At the time, these games were quite expensive and nearly always out of my financial reach. I recall going to the library with some like-minded neighbourhood friends and playing games like BattleFleet Mars, Starforce: Alpha Centauri and StarSoldier, or just reading the rules and fantasizing about the universe described in the games. ↩

-

There’s a nice history of the Sanford Fleming Building on Skulepedia, including an account of the infamous fire that engulfed the building in the Spring of 1977. ↩

-

You’ll find the code for all of the solutions in this gist. ↩

-

One of the benefits of having some exposure to math and computer science is this: If you recognize that something is a formal concept, you can extract it, and name it after the “term of art” that is well-understood. Without that exposure, you may reinvent the concept, but you are less likely to know to extract it independently and probably won’t give it a name that everyone recognizes at a glance. Thus, we can create explicit functions like

chooseandpermutations, and that is superior to having the exact same functionality performed implicitly in the code. ↩ -

But far from the only optimization! Once we grasp that the interesting thing about a queen is the number of its row and column, and then add the concept of the numbers of its NESW and NWSE diagonals, it is a fairly obvious step to go right to encoding queen positions as bits. This allows us to use very fast bitwise operations instead of reading and writing from arrays. Here’s an example in JavaScript that exploits bitwise operators and inductive search: A bitwise solution to the n-Queens problem in Javascript. ↩

-

There are some other optimizations available around exploiting horizontal or rotational symmetry to reduce the search space. For example, consider an approach where we also generate the horizontal reflection of a solution we find. In that case, after completing all the possible solutions that include a Queen in position

[0, 0], we can eliminate trying any solutions that have a queen in position[7,0]. Alas, this is a leaf, so we don’t get to prune an entire subtree, and the ratio of code complexity to gains is marginal. I found my attempt inelegant. You might want to play around with searching in different ways so that there is an elegant way to exploit horizontal and rotational symmetry to reduce the search space. ↩