In theory, JavaScript does not have classes. In practice, the following snippet of code is widely considered to be an example of a “class” in JavaScript:

function Account () {

this._currentBalance = 0;

}

Account.prototype.balance = function () {

return this._currentBalance;

}

Account.prototype.deposit = function (howMuch) {

this._currentBalance = this._currentBalance + howMuch;

return this;

}

// ...

var account = new Account();

The pattern can be extended to provide the notion of subclassing:

function ChequingAccount () {

Account.call(this);

}

ChequingAccount.prototype = Object.create(Account.prototype);

ChequingAccount.prototype.sufficientFunds = function (cheque) {

return this._currentBalance >= cheque.amount();

}

ChequingAccount.prototype.process = function (cheque) {

this._currentBalance = this._currentBalance - cheque.amount();

return this;

}

These classes and subclasses provide most of the features of classes we find in languages like Smalltalk:

- Classes are responsible for creating objects and initializing them with properties (like the current balance);

- Classes are responsible for and “own” methods, Objects delegate method handling to their classes (and superclasses);

- Methods directly manipulate an object’s properties.

This pattern has become so ingrained in JavaScript culture that ECMAScript-6, the upcoming major revision of the language, provides some “syntactic sugar” so that we can write classes and subclasses without writing the whole pattern out by hand. There is no significant semantic change, behind the scenes everything works exactly as we see it here.

Smalltalk was, of course, invented forty years ago. In those forty years, we’ve learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t work in object-oriented programming. Unfortunately, this pattern celebrates the things that don’t work, and glosses over or omits the things that work.

Even more unfortunately, the upcoming syntactic sugar doesn’t solve any of the problems with classes, but instead solves the problem of “I wish to type fewer characters,” or perhaps for the new programmer, “I don’t understand how all these moving parts actually work, so I might type it wrong, isn’t there an easier way to type it?”

the semantic problem with hierarchies

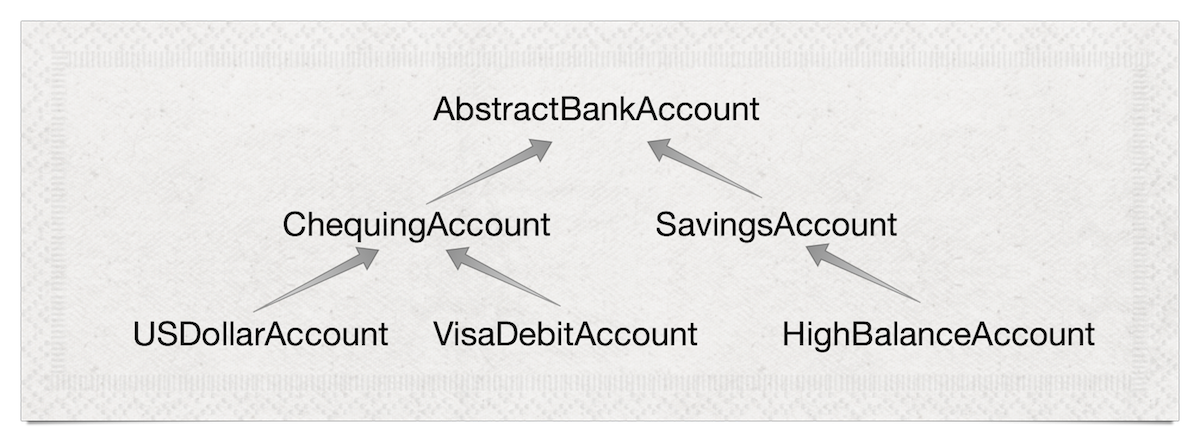

At a semantic level, classes are the building blocks of an ontology. This is often formalized in a diagram:

The idea behind class-based OO is to classify (note the word) our knowledge about objects into a tree. At the top is the most general knowledge about all objects, and as we travel down the tree, we get more and more specific knowledge about specific classes of objects, e.g. objects representing Visa Debit accounts.

Only, the real world doesn’t work that way. It really doesn’t work that way. In morphology, for example, we have penguins, birds that swim. And the bat, a mammal that flies. And monotremes like the platypus, an animal that lays eggs but nurses its young with milk.

It turns out that our knowledge of the behaviour of non-trivial domains (like morphology or banking) does not classify into a nice tree, it forms a directed acyclic graph. Or if we are to stay in the metaphor, it’s a thicket.

Furthermore, the idea of building software on top of a tree-shaped ontology would be broken even if our knowledge fit neatly into a tree. Ontologies are not used to build the real world, they are used to describe it from observation. As we learn more, we are constantly updating our ontology, sometimes moving everything around.

In software, this is incredibly destructive: Moving everything around breaks everything. In the real world, the humble Platypus does not care if we rearrange the ontology, because we didn’t use the ontology to build Australia, just to describe what we found there.

It’s sensible to build an ontology from observation of things like bank accounts. That kind of ontology is useful for writing requirements, use cases, tests, and so on. But that doesn’t mean that it’s useful for writing the code that implements bank accounts.

Class Hierarchies are the wrong semantic model, and the wisdom of forty years of experience with them is that there are better ways to compose programs.

encapsulation

Those are the semantic issues. Let’s talk about the engineering issues, let’s address classes as if we don’t care whether they represent some knowledge in the real world. Let’s presume that classes are just a tool for getting our programs to work. Are they still a problem?

Class hierarchies are a problem, even if all we want to do is use them to implement behaviour. Programs have three important use cases:

- Programs must be easy to write;

- Programs must be easy to understand;

- Programs must be easy to change.

Classes have tradeoffs for all three of these use cases, but class hierarchies are harmful with respect to understanding and changing programs, because the way they work creates an encapsulation problem.

Encapsulation is a core principle of object-oriented programming. (Other styles of programming, such as functional programming, also value encapsulation, although they implement it in different ways). In OOP, encapsulation is achieved by objects having private state and exposing a public interface in the form of methods.

JavaScript does not enforce private state, but it’s easy to write well-encapsulated programs: simply avoid having one object directly manipulate another object’s properties. Forty years after Smalltalk was invented, this is a well-understood principle.

Obviously, code will have dependencies. A will depend on B, and B will depend on C, and dependencies are transitive, so A depends on B and A also depends on C. Encapsulation doesn’t eliminate dependencies, but it does limit the scope of the dependencies: If we change B and/or C, we will not break A provided that we do not remove or change the externally observable behaviour of any of the methods A uses.

So far so good. or at least, it is if A, B and C are objects and/or functions. For example:

function depositAndReturnBalance(account, amount) {

return account.deposit(amount).balance();

}

var account = new Account();

depositAndReturnBalance(account, 100)

//=> 100

depositAndReturnBalance obviously depends on passing in an object that implements both the .deposit and .balance methods. But it doesn’t depend on how those methods are implemented: we could write this for Account and get the same behaviour:

function Account () {

this._transactionHistory = [];

}

Account.prototype.balance = function () {

return this._transactionHistory.reduce(function (acc, transaction) {

return acc + transaction;

}, 0);

}

Account.prototype.deposit = function (howMuch) {

this._transactionHistory.unshift(howMuch)

return this;

}

function depositAndReturnBalance(account, amount) {

return account.deposit(amount).balance();

}

var account = new Account();

depositAndReturnBalance(account, 100)

//=> 100

Completely different implementation of .deposit and .balance, but depositAndReturnBalance does not depend upon the implementation.

So, our class provides us with a way to encapsulate the implementation of an account balance. Great! What is the problem?

superclasses are not encapsulated

We said that encapsulation in JavaScript works when the entities involved are objects and/or functions. But what about classes?

It turns out, the relationship between classes in a hierarchy is not encapsulated. This is because classes do not relate to each other through a well-defined interface of methods while “hiding” their internal state from each other.

Here’s the way our ChequingAccount subclass implements the .process method:

ChequingAccount.prototype.process = function (cheque) {

this._currentBalance = this._currentBalance - cheque.amount();

return this;

}

If we rewrite the Account class to use a transaction history instead of a current balance, it breaks the code in ChequingAccount. In JavaScript (and other languages in the same family), classes and subclasses share access to the object’s private properties. It is not possible to change an implementation detail for Account without carefully checking every single subclass and the code depending on those subclasses to see if our internal, “private” change will break them.

Of course, we know that there are dependencies in code, so we are not surprised that subclasses depend on classes. But what is different is that this dependency is not limited in scope to a carefully curated interface of methods and behaviour. We have no encapsulation.

This problem is not a new discovery. It is well-understood, it even has a name: It’s called the Fragile Base Class Problem. Changes to classes near the root of the tree have far-reaching implications, and implications that are orders of magnitude more risky because there is no encapsulation.

Class hierarchies create brittle programs that are difficult to modify.

going forward

JavaScript first appeared in 1995, approximately 15 years after Smalltalk was first publicized. In the twenty years since then, we have learned a great many things about the good and the bad parts of JavaScript the language, and we have also learned a great many things about the good and the bad ideas in Object-Oriented Programming.

It seems obvious that we should look back and learn from what came before. Good ideas, like encapsulation, functions as first-class objects, delegation, traits, and composition should be embraced and improved upon. New ideas, like promises, should be developed.

People often say that “JavaScript isn’t Ruby,” that it’s prototype-based and not class-based. That’s true, but the opportunity is wasted when we reinvent, poorly, ideas that were invented forty years ago and have been deprecated ever since.

So if someone asks you to explain how to write a class hierarchy? Go ahead and tell them: “Don’t do that!”

(discuss on hacker news, /r/javascript, and /r/programming)