This essay is an unpublished work in progress. Please check back for updates. If you choose to share it, please mention that it is unfinished at this time.

Preamble: Developing Products “Like This”

In “Making sense of MVP,” Henrik Kniberg explains the salient distinction between fake-agile and real-agile development by contrasting two ways of developing a product iteratively, Not Like This and Like this.

The Not Like This way to develop software is to work in increments, each of which represents a portion of what we plan to build. In this way, nothing is expected to be “wasted,” since everything we build is a necessary part of the finished work.

Not Like This…

However, at each step along the way, we have potential value, but not realized value: Until the very end, the unfinished work does not actually represent value to the customer. It is not potentially shippable, potentially lovable, or even criticizable.

The Not Like This way is often called “fixed scope” development, since its axiomatic assumption is that we know exactly what we want to build, and that there is no value to be had building anything less, or anything else.

developing products like this

Whereas, the Like This way to develop software consists of building an approximation of what we plan to build, then successively refining and adding value to it with each iteration. Much is intentionally “disposable” along the way.

Like This

Unlike the Not Like This way, at each step the Like This way delivers realized value. Each “iteration” is potentially shippable, potentially lovable, and can be usefully critiqued.

The Like This way is derived from the principles of Lean Product Development. It is often called “variable scope” development, since its axiomatic assumption is that through the process of building and shipping successive increments of value, we will learn more about what we can build to deliver more value.

engineering like this

All “engineers” building products should appreciate developing products Like This, because everyone who builds a product is in the product management business, not just those with the words “product” or “manager” on their business card.

But what about building software from an engineering perspective? Can “Lean Product Development” teach us something about engineering?

Yes.

Abandoned Factory, © 2013 Forsaken Fotos, Some rights reserved

Lean Engineering

Engineering has much to learn from Lean Product Development, although not always in a literal, direct translation. The core of Lean Product Development was derived from the principles of Lean Manufacturing, then practitioners refined and evolved its practices and values from experience.

Software developers have also mined Lean Manufacturing for principles, and the result is a set of principles and values known as Lean Software Development, or “LSD.” LSD can be summarized by seven principles, four of which have direct impacts on engineering decisions:

- Eliminate waste

- Amplify learning

- Decide as late as possible

- Deliver as fast as possible

Today, we are going to look at how the principle of eliminating waste can guide our engineering choices. We will focus on engineering to support Lean Product Development, but we will see how we can apply LSD to more traditional fixed scope projects.

Car breaker’s yard, © 2014 Picturepest, some rights reserved

Eliminating Waste

The key principle of LSD is to eliminate waste. Waste in software development is any work we do that does not contribute to realized value. It is not limited to coding: Other activities–such as meetings–that do not help the team deliver value are also considered waste.

wasteful code

Many developers feel that things should be written in such a way that they can be extended without rewriting anything. This is a misguided belief based on a misunderstanding of waste. In fact, a careless pursuit of code that will never be rewritten can actually create waste.

Consider our project to build a car: We know from bitter experience that customers are never satisfied with just cars. They often come back and say they want a car that can fly. But if we build a car that cannot fly, we cannot later easily just bolt wings and an engine onto our car-that-was-not-designed-to-fly. We would need to reëngineer our car.

For example, cars contain speedometers that report a single measurement, ground speed in kilometres per hour. The typical mechanism for computing speed uses the rotation of the tires. But aircraft report two measurements, air speed and ground speed. Air speed is typically computed using a pilot tube, while groundspeed is typically computed using triangulation.

Thus, putting an automotive speedometer into our car works when we ship the car, but we must “throw it away” should we decide to build a flying car. So we might decide to get clever, and make a speedometer that uses GPS instead of tire rotation.

But a GPS unit is more expensive and complicated than a tire rotation unit. So from the perspective of shipping a car, a GPS-based speedometer represents wasteful engineering. Deciding to ship a GPS speedometer began by trying to avoid waste in the future, but it ended with creating waste now.

Taken to a ridiculous extreme, such thinking will result with us delivering a car that flies:

The Terrafugia Flying Car, © 2012 Steve Cypher, some rights reserved

Now this seems like hyperbole, would we really deliver a flying car when asked to build a car? But consider that we can easily overbuild a car without bolting wings onto it. Our example was a GPS-based speedometer. But let us consider another way to create engineering waste: We can build our car with excess architecture.

wasteful architecture

Many engineers, when faced with a car to build, begin by selecting a framework, one that promises us unparalleled flexibility. With a framework in hand we can build cars, trains, or aeroplanes. Plug-ins are provided for cruise ships and hovercrafts. We don’t have to actually build wings right now, but it will be so easy to add them later.

Even if we don’t add wings now, or use a GPS-based speedometer, the price of such flexibility is that we build our car out of layers of abstraction. We don’t write speedometer code directly, we implement IVelocityGauge and configure it with an IDataSource that is a wheel today but can be a GPS tomorrow.

Everything we do must be done via an abstraction, through a layer of indirection. Such abstractions are a win for framework and library authors, because they allow the framework to serve a wider audience. But each framework user is now paying an abstraction tax.

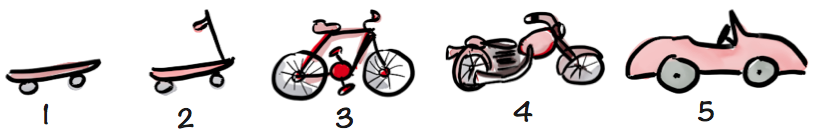

That abstraction tax is waste, albeit a more hidden waste than using GPS for a speedometer, or bolting wings onto a car. From an engineering perspective, eschewing that waste is lean software development, whether building software in variable scope style (skateboard, scooter, bicycle, motorcycle, car), or in a fixed scope style (wheels, transmission, chassis, car). But when building in either style, the lean software developer eschews hidden or visible waste, building only what is necessary for the most immediate release.

Debt, © 2009 Jason Taellious, some rights reserved

technical debt

Developers easily grasp the notion that developing features we do not need, is wasteful, and that developing with abstractions and layers of indirection we do not need, is also wasteful. But there is another kind of waste that engineers struggle with every day, technical debt.

Technical debt arises when we optimize for a short term result, making choices that sacrifice the long-term effectiveness of the team. For example, code that is poorly factored may have been quickest to develop in the first place, but subsequent modification and extension is slowed by the presence of anti-patterns such as tightly coupled code, or “God Objects.”1

Work we perform to overcome the friction and obstruction of technical debt, is waste.

What makes technical debt a special case is that eliminating the waste of technical debt is often in tension with eliminating architectural waste. If we write code such that it is easy to read by ourselves or others in the future, if we optimize for making it easy to modify and extend, we need more time to write it than if we optimize for making it work now, for the specific use case in front of us.

When faced with a new task, we are tempted to weigh the architectural waste in the present, against the expected future value of the technical debt waste, then “make the calculation” and decide how much architecture will result in the least waste over the lifetime of the code.

This is sensible in theory, but not in practice.

Junkyard, © 2010 barz51, some rights reserved

Decision-making Scope

The practical problem with balancing architectural waste on a task against technical debt, is that architectural waste is a local and short-term concern, while technical debt is a global and long-term concern.

To illustrate this, let’s consider what a feature we are going to implement in JavaScript. We might decide that it is fastest and simplest to write “Vanilla JS” to implement a feature. However, every developer has their own particular idea of what constitutes “Vanilla JS.” Thus an application or service written by several different developers, each of whom writes in their personal dialect of “Vanilla JS,” can wind up being a hodgepodge of barely compatible piles of code, with much overlap and duplication of functionality, precariously glued together.

That would lead to waste, even though each developer was working to avoid waste.

Given this reality, we might decide that to prevent the outcome being wasteful, we should invest our time learning and implementing an application framework. The framework will impose a standard way to solve many problems, and while we will lose some time on our individual feature, but if everyone programs to the same framework, we’ll all eliminate the waste of working with a badly integrated set of idiosyncratic features. Many teams consider this an excellent choice.

Choosing a Framework is a global choice. Obviously, each developer cannot pick their own framework. is a choice that affects every programmer on every team that works with the code base. Frameworks are global choices.

Second, let’s consider the question of whether to write a particular feature using bog standard imperative JavaScript, or to write it in a more functional, immutable data style.

We might reason that the team we have today is familiar with functional programming style, and that an immutable data style will allow the team today to have more confidence in getting a feature written quickly without sacrificing reliability. (Other teams might have a different perspective, but let’s go with this one for the sake of argument.)

But we might also fear that in the future, we may have individually moved on to other projects. Will our replacements be as comfortable working with ideas like copy-on-write semantics? If not, we might be shipping faster topday, but creating waste in the future as our new colleagues have to get up to speed on our programming style.

Decisions about programming style, patterns, and paradigms are long-term concerns.

As a rule, the tension between eliminating waste in a lean programming fashion and managing technical debt is the tension between optimizing for local, short-term results against optimizing for global, long-term results.

Recycle, © 2014 Carol VanHook, Some rights reserved

Managing the impedance mismatch between scopes

So as we’ve seen, the problem with balancing architectural waste on tasks against technical debt, is that architectural waste is a local and short-term concern, while technical debt is a global and long-term concern.

Our experience from all walks of life (not just software development, and not even just business), is that it is ineffective to make decisions about global or general issues, on the basis of local or specific symptoms. To make good decisions about global issues, we need to use global information. We have to step back and look at all of the costs and impacts across all of the affected projects and people.

Likewise, our experience from all walks of life, is also that it is ineffective to make decisions with long-term consequences, on the basis of short-term impact. To make good decisions about long-term issues, we need to think about the lifetime of the costs and consequences, not just in terms of how we will be affected in the short term.

The inverses of these two observations are also true: It is ineffective to make decisions that have local consequences on a global basis. And it is ineffective to make decisions that have short-term consequences, by weighing long-term outcomes.

The appropriate way to make all decisions is to determine the scope of the decision, and then make the decision within the context of its scope.

Decisions with local and short-term impact should be made on a local basis—by the people affected, and on a short-term time scale. We do this in software development by making some decisions within the team, and by making and revisiting decisions on a short-term basis. This is the principle behind developers using the Pomodoro Technique, behind agile teams having daily stand-ups, and behind iterative development disciplines such as Scrum. Developers are encouraged to exercise autonomy over decisions that have only personal consequences. Those that have a team and very short-term impact are discussed at stand-ups, and decisions that have a two-week or monthly impact are made by the team during sprint planning and review ceremonies.

The key to making good local and short-term decisions is to exercise judgment about whether an issue is scoped to a developer, a team, or the broader engineering organization, and to make sure that there are mechanisms in place to make developer-specific and team-specific decisions on the appropriate short-term time-scale. This is in keeping with the third principle of lean development, making decisions as late as possible. Short-term decisions are made as close as possible to when we need to make them.

Wasted Money, © 2009 Karl Birrane, Some rights reverved

Playing the Long Game

Global and long-term decisions should not be made by developers or teams, nor should they be made in a daily stand-up or iteration-specific ceremony. Global decisions should be made by people familiar with the ramifications for all the teams involved, be they managers in a hierarchal organization, or team ambassadors in a flat organization. Likewise, they should be made on a long-term rhythm, not on an ad hoc basis when teams feel they have an itch they want to scratch.

Whn global and long-term decisions are made on a small scope and when teh decision is dominated by short-term concerns, the risk of making a poor decision is very high. Statistically, consequences ar enot evenly spread across an organization, or evenly spread over time. Asa result, some teams may not see the need for making a crucial investment in adopting a new programming language. Another team may suffer from so much short-term pain tha they are tempted to rewrite an entire application. Another team may bein an expensive investment in a reasonably good idea, and thus be too busy to consider an even better idea that arises in the next iteration.

Globally scoped decisions with long-term consequences need to be weighed and judged against other globally scoped decisions with long-term consequences. They must be made infrequently enough that we have gathered enough information to avoid wastful thrashing or missed opportunities.

have your say

Have an observation? Spot an error? You can open an issue, or even edit this post yourself!

notes

-

“Technical debt” isn’t an exact metaphor, in that financial debt must nearly always be repaid, and the amount to be repaid is known with certainty. Whereas technical debt might or might not need to be repaid, and the amount of friction caused by technical debt is not know with certainty. ↩