Once upon a time, there was a language called C,1 and this language had something called a struct, and you could use it to make heterogeneously aggregated data structures that had members. The key thing to know about C is that when you have a struct called currentUser, and a member like id, and you write something like currentUser.id = 42, the C complier turned this into extremely fast assembler instructions. Same for int id = currentUser.id.

Also of importance was that you could have pointers to functions in structs, so you could write things like currentUser->setId(42) if you preferred to make setting an id a function, and this was also translated into fast assembler.

And finally, C programming has a very strong culture of preferring “extremely fast” to just “fast,” and thus if you wanted a C programmer’s attention, you had to make sure that you never do something that is just fast when you could do something that is extremely fast. This is a generalization, of course. I’m sure that if we ask around, we’ll eventually meet both C programmers who prefer elegant abstractions to extremely fast code.

java and javascript

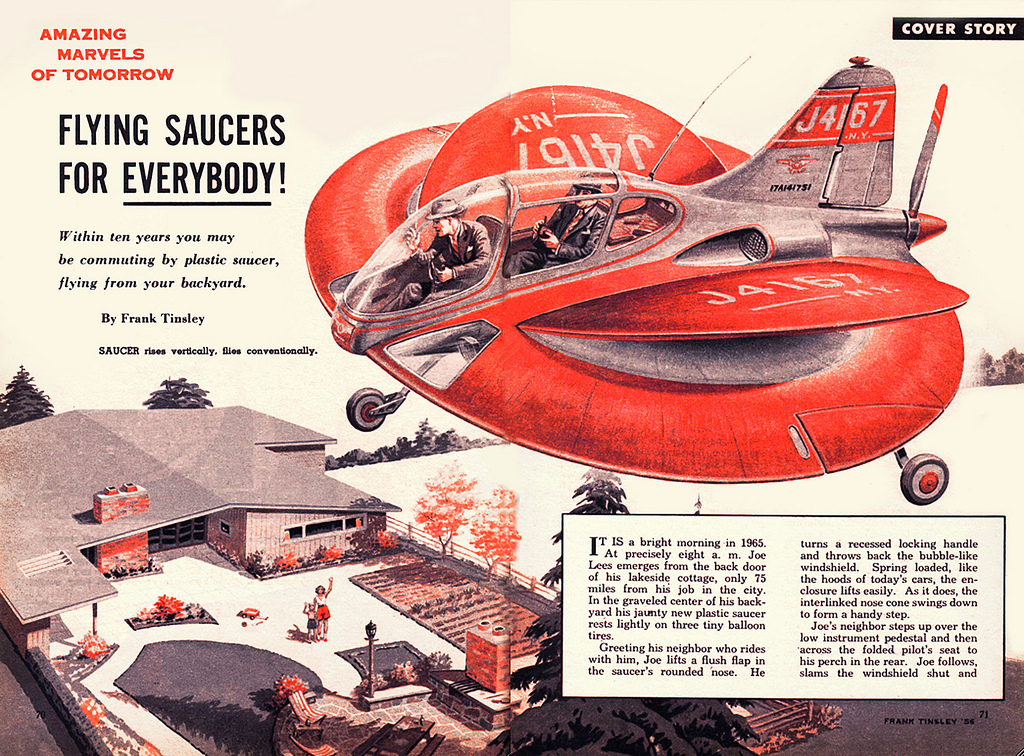

Then there was a language called Java, and it was designed to run in browsers, and be portable across all sorts of hardware and operating systems, and one of its goals was to get C programmers to write Java code in the browser instead of writing C that lived in a plugin. Or rather, that was one of its strategies, the goal was for Sun Microsystems to stay relevant in a world that Microsoft was commoditizing, but that is another chapter of the history book.

So the nice people behind Java gave it C-like syntax with the braces and the statement/expression dichotomy and the dot notation. They have “objects” instead of structs, and objects have a lot more going on than structs, but Java’s designers made a distinction between currentUser.id = 42 and currentUser.setId(42), and made sure that one was extremely fast and the other was just fast. Or rather, that one was fast, and the other was just ok compared to C, but C programmers could feel like they were doing important thinking when deciding whether id ought to be directly accessed for performance or indirectly accessed for elegance and flexibility.

History has shown that this was the right way to sell a new language. History has also shown that the actual performance distinction was irrelevant to almost everybody. Performance is only for now, code flexibility is forever.

Well, it turned out that Sun was right about getting C programmers to use Java (it worked on me, I ditched CodeWarrior and Lightspeed C), but wrong about using Java in browsers. Instead, people started using another language called JavaScript to write code in browsers, and used Java to write code on servers.

Will it surprise you to learn that JavaScript was also designed to get C programmers to write code? And that it went with the C-like syntax with curly braces, the statement/expression dichotomy, and dot notation? And although JavaScript has a thing that is kinda-sorta like a Java object, and kinda-sorta like a Smalltalk dictionary, will it surprise you to learn that JavaScript also has a distinction between currentUser.id = 42 and currentUser.setId(42)? And that originally, one was slow, and the other dog-slow, but programmers could do important thinking about when to optimize for performance and when to give a hoot about programmer sanity?

No, it will not surprise you to learn that it works kinda-sorta like C in the same way that Java kinda-sort works like C, and for exactly the same reason. And the reason really doesn’t matter any more.

the problem with direct access

Very soon after people begun working with Java at scale, they learned that directly accessing instance variables was a terrible idea. JIT compilers narrowed the performance difference between currentUser.id = 42 and currentUser.setId(42) to almost nothing of relevance to anybody, and code using currentUser.id = 42 or int id = currentUser.id was remarkably inflexible.

There was no way to decorate such operations with cross-cutting concerns like logging or validation. You could not override the behaviour of setting or getting an id in a subclass. (Java programmers love subclasses!)

Meanwhile, JavaScript programmers were also writing currentUser.id = 42, and eventually they too discovered that this was a terrible idea. One of the catalysts for change was the arrival of frameworks for client-side JavaScript applications. Let’s say we have a ridiculously simple person class:

class Person {

constructor (first, last) {

this.first = first;

this.last = last;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.first} ${this.last}`;

}

};

And an equally ridiculous view:

class PersonView {

constructor (person) {

this.model = person;

}

// ...

redraw () {

document

.querySelector(`person-${person.id}`)

.text(person.fullName())

}

}

Every time we update the person class, we have to remember to redraw the view:

const currentUser = new Person('Reginald', 'Braithwaite');

const currentUserView = new PersonView(currentUser);

currentUserView.redraw();

currentUser.first = 'Ragnvald';

currentUserView.redraw();

Why does this matter?

Well, if you can’t control where certain responsibilities are handled, you can’t really organize your program. Subclasses, methods, mixins and decorators are techniques: What they make possible is choosing which code is responsible for which functionality.

And that’s the whole thing about programming: Organizing the functionality. Direct access does not allow you to organize the functionality associated with getting and setting properties, it forces the code doing the getting and setting to also be responsible for anything else associated with getting and setting.

get and set

It didn’t take long for JavaScript library authors to figure out how to make this go away by using a get and set method. Stripped down to the bare essentials for illustrative purposes, we could write this:

class Model {

constructor () {

this.listeners = new Set();

}

get (property) {

this.notifyAll('get', property, this[property]);

return this[property];

}

set (property, value) {

this.notifyAll('set', property, value);

return this[property] = value;

}

addListener (listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

}

deleteListener (listener) {

this.listeners.delete(listener);

}

notifyAll (message, ...args) {

for (let listener of this.listeners) {

listener.notify(this, message, ...args);

}

}

}

class Person extends Model {

constructor (first, last) {

super();

this.set('first', first);

this.set('last', last);

}

fullName () {

return `${this.get('first')} ${this.get('last')}`;

}

};

class View {

constructor (model) {

this.model = model;

model.addListener(this);

}

}

class PersonView extends View {

// ...

notify(notifier, method, ...args) {

if (notifier === this.model && method === 'set') this.redraw();

}

redraw () {

document

.querySelector(`person-${this.model.id}`)

.text(this.model.fullName())

}

}

Our new Model superclass manually manages allowing objects to listen to the get and set methods on a model. If they are called, the “listeners” are notified via the .notifyAll method. We use that to have the PersonView listen to its Person and call its own .redraw method when a property is set via the .set method.

So we can write:

const currentUser = new Person('Reginald', 'Braithwaite');

const currentUserView = new PersonView(currentUser);

currentUser.set('first', 'Ragnvald');

And we don’t need to call currentUserView.redraw(), because the notification built into .set does it for us.

We can do other things with .get and .set, of course. Now that they are methods, we can decorate them with logging or validation if we choose. Methods make our code flexible and open to extension. For example, we can use an ES.later decorator to add logging advice to .set:

const after = (behaviour, ...methodNames) =>

(clazz) => {

for (let methodName of methodNames) {

const method = clazz.prototype[methodName];

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, methodName, {

value: function (...args) {

const returnValue = method.apply(this, args);

behaviour.apply(this, args);

return returnValue;

},

writable: true

});

}

return clazz;

}

function LogSetter (model, property, value) {

console.log(`Setting ${property} of ${model.fullName()} to ${value}`);

}

@after(LogSetter, 'set')

class Person extends Model {

constructor (first, last) {

super();

this.set('first', first);

this.set('last', last);

}

fullName () {

return `${this.get('first')} ${this.get('last')}`;

}

};

Whereas we can’t do anything like that with direct property access. Mediating property access with methods is more flexible than directly accessing properties, and this allows us to organize our program and distribute responsibility properly.

Note: All the ES.later class decorators can be used in vanilla ES 6 code as ordinary functions. Instead of

@after(LogSetter, 'set') class Person extends Model {...}, simply writeconst Person = after(LogSetter, 'set')(class Person extends Model {...})

getters and setters in javascript

The problem with getters and setters was well-understood, and the stewards behind JavaScript’s evolution responded by introducing a special way to turn direct property access into a kind of method. Here’s how we’d write our Person class using “getters” and “setters:”

class Model {

constructor () {

this.listeners = new Set();

}

addListener (listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

}

deleteListener (listener) {

this.listeners.delete(listener);

}

notifyAll (message, ...args) {

for (let listener of this.listeners) {

listener.notify(this, message, ...args);

}

}

}

const _first = Symbol('first'),

_last = Symbol('last');

class Person extends Model {

constructor (first, last) {

super();

this.first = first;

this.last = last;

}

get first () {

this.notifyAll('get', 'first', this[_first]);

return this[_first];

}

set first (value) {

this.notifyAll('set', 'first', value);

return this[_first] = value;

}

get last () {

this.notifyAll('get', 'last', this[_last]);

return this[_last];

}

set last (value) {

this.notifyAll('set', 'last', value);

return this[_last] = value;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.first} ${this.last}`;

}

};

When we preface a method with the keyword get, we are defining a getter, a method that will be called when code attempts to read from the property. And when we preface a method with set, we are defining a setter, a method that will be called when code attempts to write to the property.

Getters and setters needn’t actually read or write any properties, they can do anything. But in this essay, we’ll talk about using them to mediate property access. With getters and setters, we can write:

const currentUser = new Person('Reginald', 'Braithwaite');

const currentUserView = new PersonView(currentUser);

currentUser.first = 'Ragnvald';

And everything still works just as if we’d written currentUser.set('first', 'Ragnvald') with the .set-style code.

Getters and setters allow us to have the semantics of using methods, but the syntax of direct access.

an after combinator that can handle getters and setters

Getters and setters seem at first glance to be a magic combination of familiar syntax and powerful ability to meta-program. However, a getter or setter isn’t a method in the usual sense. So we can’t decorate a setter using the exact same code we’d use to decorate an ordinary method.

With the .set method, we could directly access Model.prototype.set and wrap it in another function. That’s how our decorators work. But there is no Person.prototype.first method. Instead, there is a property descriptor we can only introspect using Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor() and update using Object.defineProperty().

For this reason, the naïve after decorator given above won’t work for getters and setters.2 We’d have to use one kind of decorator for methods, another for getters, and a third for setters. That doesn’t sound like fun, so let’s modify our after combinator so that you can use a single function with methods, getters, and setters:

function getPropertyDescriptor (obj, property) {

if (obj == null) return null;

const descriptor = Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, property);

if (obj.hasOwnProperty(property))

return Object.getOwnPropertyDescriptor(obj, property);

else return getPropertyDescriptor(Object.getPrototypeOf(obj), property);

};

const after = (behaviour, ...methodNames) =>

(clazz) => {

for (let methodNameExpr of methodNames) {

const [_, accessor, methodName] = methodNameExpr.match(/^(?:(get|set) )(.+)$/);

const descriptor = getPropertyDescriptor(clazz.prototype, methodName);

if (accessor == null) {

const method = clazz.prototype[methodName];

descriptor.value = function (...args) {

const returnValue = method.apply(this, args);

behaviour.apply(this, args);

return returnValue;

};

descriptor.writable = true;

}

else if (accessor === "get") {

const method = descriptor.get;

descriptor.get = function (...args) {

const returnValue = method.apply(this, args);

behaviour.apply(this, args);

return returnValue;

};

descriptor.configurable = true;

}

else if (accessor === "set") {

const method = descriptor.set;

descriptor.set = function (...args) {

const returnValue = method.apply(this, args);

behaviour.apply(this, args);

return returnValue;

};

descriptor.configurable = true;

}

Object.defineProperty(clazz.prototype, methodName, descriptor);

}

return clazz;

}

Now we can write:

const notify = (name) =>

function (...args) {

this.notifyAll(name, ...args);

};

@after(notify('set'), 'set first', 'set last')

@after(notify('get'), 'get first', 'get last')

class Person extends Model {

constructor (first, last) {

super();

this.first = first;

this.last = last;

}

get first () {

return this[_first];

}

set first (value) {

return this[_first] = value;

}

get last () {

return this[_last];

}

set last (value) {

return this[_last] = value;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.first} ${this.last}`;

}

};

We have now decoupled the code for notifying listeners from the code for getting and setting values. Which provokes a simple question: If the code that tracks listeners is already decoupled in Model, why shouldn’t the code for triggering notifications be in the same entity?

There are a few ways to do that. We’ll use a universal mixin instead of stuffing that logic into a superclass:

const Notifier = mixin({

init () {

this.listeners = new Set();

},

addListener (listener) {

this.listeners.add(listener);

},

deleteListener (listener) {

this.listeners.delete(listener);

},

notifyAll (message, ...args) {

for (let listener of this.listeners) {

listener.notify(this, message, ...args);

}

}

}, {

notify (name) {

return function (...args) {

this.notifyAll(name, ...args);

}

}

});

This permits us to write:

@Notifier

@after(Notifier.notify('set'), 'set first', 'set last')

@after(Notifier.notify('get'), 'get first', 'get last')

class Person {

constructor (first, last) {

this.init();

this.first = first;

this.last = last;

}

get first () {

return this[_first];

}

set first (value) {

return this[_first] = value;

}

get last () {

return this[_last];

}

set last (value) {

return this[_last] = value;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.first} ${this.last}`;

}

};

What have we done? We have incorporated getters and setters into our code, while maintaining the ability to decorate them with added functionality as if they were ordinary methods.

That’s a win for decomposing code. And it points to something to think about: When all you have are methods, you’re encouraged to make heavyweight superclasses. That’s why so many frameworks force you to extend their special-purpose base classes like Model or View.

But when you find a way to use mixins and decorate methods, you can decompose things into smaller pieces and apply them where they are needed. This leads in the direction of using collections of libraries instead of a heavyweight framework.

summary

Getters and setters allow us to maintain the legacy style of writing code that appears to directly access properties, while actually mediating that access with methods. With care, we can update our tooling to permit us to decorate our getters and setters, distributing responsibility as we see fit and freeing us from dependence upon heavyweight base classes.

(discuss on Hacker News)

Post Scriptum

This post uses listening to property setters as an excuse to discuss the getter and setter mechanisms, and ways to decorate them so that we can organize code around concerns.

Of course, propagating changes through explicit notification is not the only way to organize code that needs to manage dependencies on data changing. It’s beyond the scope of this post to discuss the many alternatives, but readers have suggested exploring Object.observe and working with immutable data.

one more thing

Rubyists scoff at:

get first () {

return this[_first];

}

set first (value) {

return this[_first] = value;

}

get last () {

return this[_last];

}

set last (value) {

return this[_last] = value;

}

Rubyists would use the built-in class method attr_accessor to write them for us. So just for kicks, we’ll write a decorator that writes getters and setters. The raw values will be stored in an attributes map:

function attrAccessor (...propertyNames) {

return function (clazzOrObject) {

const target = clazzOrObject.prototype || clazzOrObject;

for (let propertyName of propertyNames) {

Object.defineProperty(target, propertyName, {

get: function () {

if (this.attributes)

return this.attributes[propertyName];

},

set: function (value) {

if (this.attributes == undefined)

this.attributes = new Map();

return this.attributes[propertyName] = value;

},

configurable: true,

enumerable: true

})

}

return clazzOrObject;

}

}

Now we can write:

@Notifier

@attrAccessor('first', 'last')

@after(Notifier.notify('set'), 'set first', 'set last')

@after(Notifier.notify('get'), 'get first', 'get last')

class Person {

constructor (first, last) {

this.init();

this.first = first;

this.last = last;

}

fullName () {

return `${this.first} ${this.last}`;

}

};

attrAccessor takes a list of property names and returns a decorator for a class. It writes a plain getter or setter function for each property, and all the properties defined are stored in the .attributes hash. This is very convenient for serialization or other persistance mechanisms.

(It’s trivial to also make attrReader and attrWriter functions using this template. We just need to omit the set when writing attrReader and omit the get when writing attrWriter.)

-

There was also a language called BCPL, and others before that, but our story has to start somewhere, and it starts with C. ↩

-

Neither will the

mixinrecipe we’ve evolved in previous posts like Using ES.later Decorators as Mixins. It can be enhanced to add a special case for getters, setters, and other concerns like working with POJOs. For example, Andrea Giammarchi’s Universal Mixin. ↩