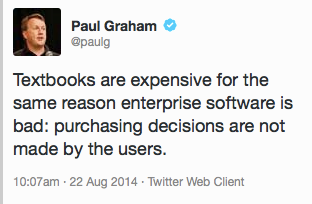

Paul Graham tweeted something interesting, and worth discussing. But first, a fabulous story, The Chicken and the Pig:

A Pig and a Chicken are walking down the road.

The Chicken says: “Hey Pig, I was thinking we should open a restaurant!”

Pig replies: “Hm, maybe, what would we call it?”

The Chicken responds: “How about ‘ham-n-eggs’?”

The Pig thinks for a moment and says: “No thanks. I’d be committed, but you’d only be involved!”

The story is usually told to illustrate the effects that differening levels of commitment have on stakeholders in a project. When writing departmental software, the manager of the department, who is accountable for its productivity, is a pig. The company’s IT manager, on the other hand, is usually a chicken.

This manifests itself in behaviour such as the IT manager demanding SharePoint compatibility, because they’re accountable for the ops personnel training budget.

Such a decision might make the software less usable for the department, but the IT Manager is not responsible for the department’s productivity, and this produces a natural tension between the two managers.

But what about the tweet?

Textbooks are not just expensive, they’re usually terrible. If they were great, the cost would be a minor concern. But when you have a medicore product, it’s natural to resent being forced to pay through the nose to own it.

terrible textbooks

The mechanism behind terrible textbooks is the same mechanism behind terrible enterprise software. In my experience, enterprise software can be effective when selected by people who don’t have to use it. The key is whether it is selected by pigs. People who have to use it are one kind of pig. People accountable for the productivity it delivers are another kind of pig. As long as an enterprise software project is driven by pigs and the chickens are restricted to an advisory capacity, you can have effective software.

But even one chicken with direct management authority or veto power can ruin an enterprise project: They “coattail” requirements that suit their own objectives at the expense of the project’s success, and you end up with nonsense. (This happens everywhere. Microsoft is suffering now because its “cash cows,” Windows and Office, behaved like chickens on steriods for decades, making almost every other division and department subordinate to their goals.)

So about textbooks. It’s fairly obvious that the problem with textbook quality and price is that the students are pigs and everyone else–faculty, administration, publishers–are chickens with authority. Fixing this problem could be done by routing around the whole system. For example, make universities irrelevant.

why we are about chickens and pigs

Regardless of what we do or do not do with textbooks, we should always pay attention to the chickens and pigs dynamic. It’s an enormously indsidious pheneomenon, and wherever you find it, you find waste and human misery.

Which also means, wherever you find it, there are opportunities to make money and to make people’s lives better. If you figure out how to disrupt textbooks, you’re cracking a billion dollar market, and helping people get an affordable education. If you figure out how to help enterprise software developers work together, better, you’re cracking another billion dollar market and again making people happy doing something they love.

So in conlusion… Textbooks are an example of the chicken and egg dynamic. It’s an important dynamic to understand, because it is very common, and if you can crack it, you can make money while making people’s lives better.

Which reminds me of another thing I once read:

“Where there’s muck, there’s brass.”—Paul Graham